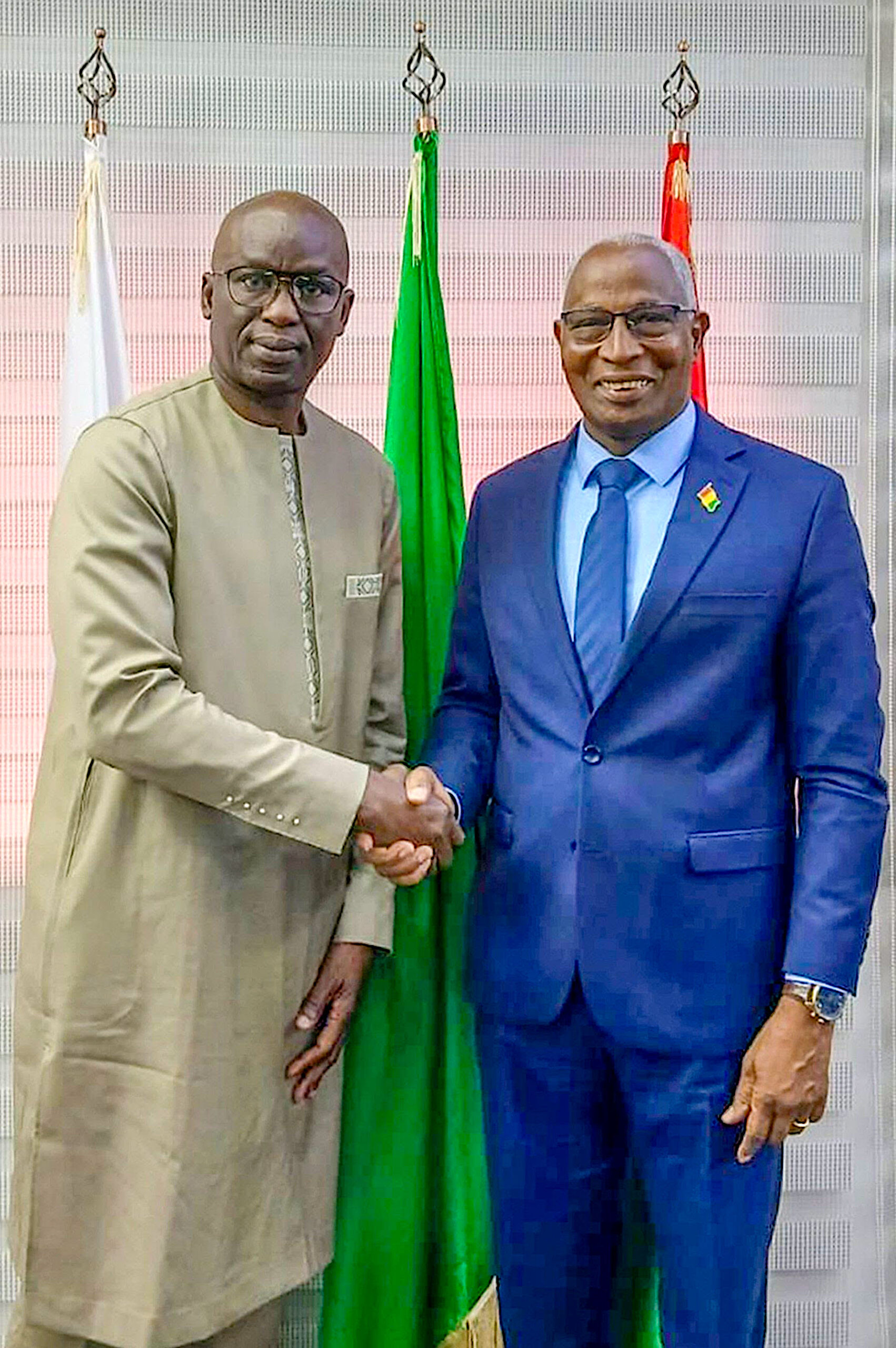

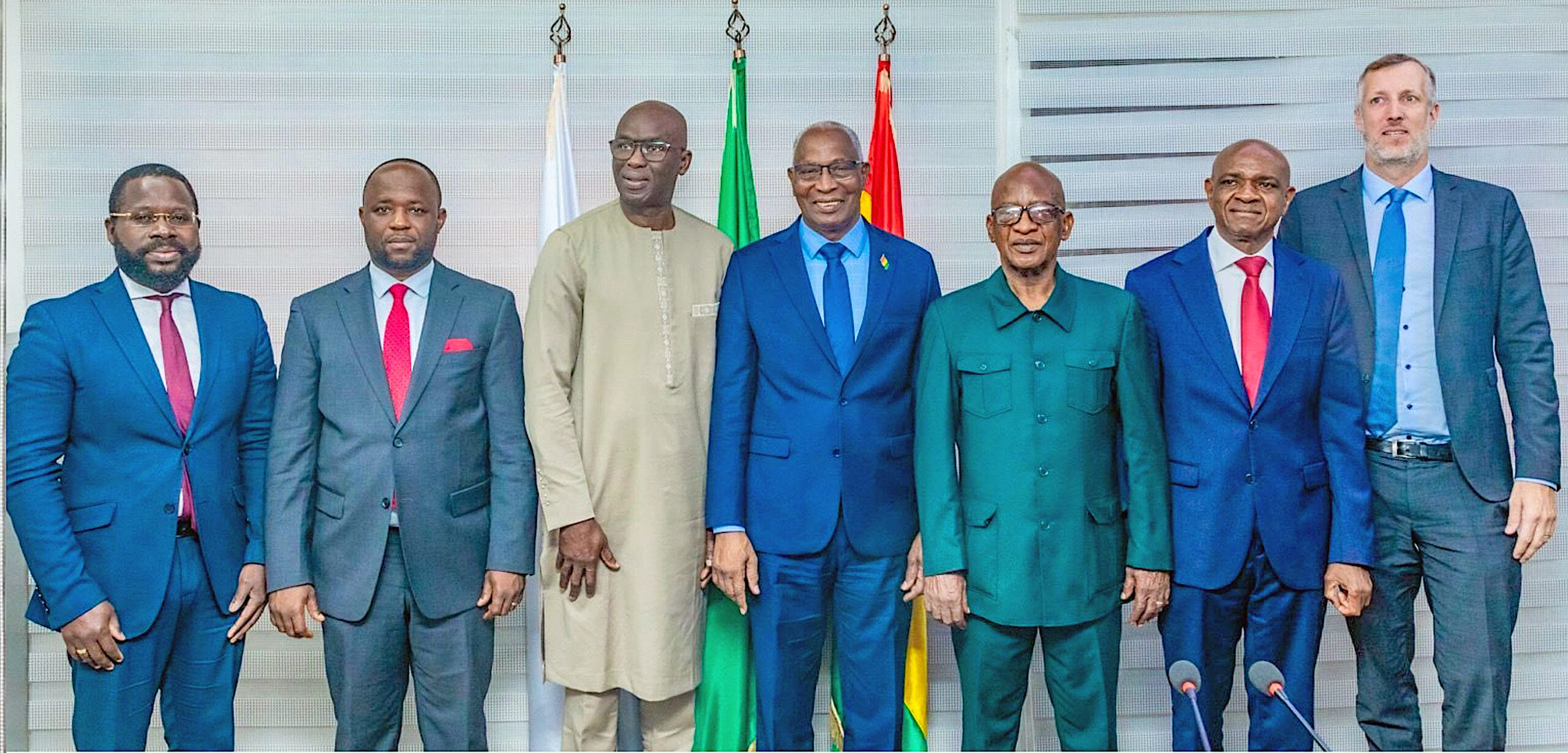

Mame Mandiaye Niang, Deputy Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (left), with Guinea’s Prime Minister Amadou Oury Bah

Reparations, Appeals, and Political Risk: Guinea’s Justice in Focus

ICC Deputy Prosecutor Visits Amid Guinea’s Judicial Uncertainty

Conakry/The Hague: The killings, disappearances and sexual violence that engulfed Conakry’s national stadium on September 28, 2009, remain one of the most painful chapters in Guinea’s modern history. For thousands of survivors, the memories are not abstractions but daily reminders of a day when a political rally spiralled into a massacre. Sixteen years later, the country continues to wrestle with how to deliver credible justice, protect victims, and restore national dignity.

Against this backdrop, Mame Mandiaye Niang, Deputy Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC), arrived in Guinea for a three-day visit from November 17 to 19, 2025. His mission came at a sensitive moment. Guinea’s domestic judicial process—opened in 2022 after years of delays—has progressed unevenly, marked by political turbulence, public frustration and lingering questions about whether national institutions can fully deliver justice for the mass violence that took place at the stadium.

Sixteen years after the massacre, Guinea’s most significant criminal process since independence remains suspended between progress and paralysis. Survivors still wait, courts still deliberate, governments still promise, and international observers still watch a justice system that advances one month and retreats the next. Niang’s fifth visit was less a ceremonial check-in than a probe into why Guinea’s long-delayed path to accountability continues to be fragile.

The September 28, 2009, crackdown left hundreds dead or wounded, scores disappeared, and more than a hundred women subjected to sexual violence—crimes that the ICC’s preliminary examination, launched in October 2009, later assessed as likely amounting to crimes against humanity.

In 2022, after Guinea finally opened its domestic trial on the 13th anniversary of the massacre, the ICC closed its preliminary examination. The message at the time was clear: Guinea would handle this case within its own judicial system, with ICC support from the sidelines.

Three years later, however, Guinea’s execution of that responsibility remains under scrutiny—not only from The Hague but from Guineans themselves. Niang’s meetings with Prime Minister Amadou Oury Bah, Justice Minister Yaya Kaïraba Kaba, UN human rights representatives, victims’ associations and civil society groups revealed a justice process that is still inching forward, despite having all the legal foundations it requires.

Guinea’s 2022 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the ICC commits the state to transparency, non-interference, witness protection, adequate resourcing and regular updates. While rarely disputed on paper, the MoU’s provisions have been implemented unevenly, raising questions about whether the process can deliver durable outcomes.

Niang publicly urged Guinean authorities to accelerate the appeals in the main trial and launch related cases that remain stalled. His statement that “completing these proceedings is essential” for victims and for Guinea was framed diplomatically but read by some observers as a critique of persistent delays. The emphasis on the case as a “landmark example of national justice” highlighted a broader reality: Guinea risks becoming a cautionary tale if political decisions continue to undermine judicial outcomes.

The most destabilising episode came earlier this year when a presidential pardon was granted to Moussa Dadis Camara, the former junta leader convicted in 2024 for his role in the stadium massacre. The pardon, granted on March 28, 2025, by President Mamady Doumbouya for health reasons, triggered Camara’s immediate release and drew criticism from the ICC, the United Nations, and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) as a potential risk of impunity amid ongoing appeals. While no formal decree reversed the pardon, subsequent developments—including Camara’s departure abroad in April 2025 and sustained international pressure, notably statements from UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk—effectively neutralised its impact on the judicial process. Nevertheless, the episode fractured public trust and highlighted the vulnerability of Guinea’s justice system to executive influence. Civil society groups and legal analysts noted that even such operational interference demonstrated the absence of institutional safeguards envisioned in the ICC Memorandum of Understanding. Judicial officers privately acknowledged operating under ongoing political pressure, particularly in high-profile cases, which has contributed to slow-moving appeals and persistent procedural hurdles.

Victim support, another core pillar of the MoU, also remains insufficient. Survivors who testified continue to face exposure, social stigma and economic hardship. Women who endured sexual violence report hostile community environments, and many still lack access to psychological care. Deputy Prosecutor Niang highlighted the presidential decree on reparations as a positive step towards redress and national reconciliation, and encouraged further progress in implementing reparations for victims. He also discussed the importance of preserving the memory of the events of 28 September 2009 and reiterated the Office’s willingness to contribute to such efforts at the appropriate time, including through the transfer of the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP)’s archives relating to the situation in Guinea.

Witness protection remains uneven. Lawyers involved in the trials describe thin resources, inconsistent coordination between agencies, and uneven application of risk assessments. Without a functioning protection system, witnesses may be discouraged from participating in pending appeals and related trials.

Addressing the association of victims of the September 28, 2009, events, Deputy Prosecutor Niang expressed his deep appreciation for the continued dialogue between the Office and the victims, their associations and civil society actors, and reaffirmed the Office’s firm commitment to remain actively engaged with civil society and national authorities, making sure that justice for the 28 September 2009 events is delivered.

“It is only when all of us join our efforts that we can make sure that those who committed heinous crimes are held accountable. Victims remain at the heart of this process, and we can never give up,” Deputy Prosecutor Niang stated.

Despite these challenges, Niang emphasised that victims “remain at the heart of this process.” Yet survivor groups increasingly argue they are marginalised in decision-making, expressing frustration that years of testimony, hearings and public engagement have not resulted in faster appellate decisions or firmer safeguards against political interference. The ICC’s visits, while valued, have not materially altered survivors’ lived reality of uncertainty.

Political factors remain the most decisive variable in the trial’s future trajectory. Executive influence over judicial appointments, budget allocations, and procedural approvals can either accelerate or stall appeals and related cases. The Camara pardon episode demonstrated that political expediency can temporarily override judicial determinations, signalling to magistrates, prosecutors and witnesses that rulings carry political as well as legal consequences.

Electoral cycles, party rivalries, and security concerns in Guinea may further complicate proceedings, as governments might seek to contain or delay politically sensitive trials to avoid unrest. International support and MoU commitments provide structural safeguards, but they cannot insulate the courts from deliberate political obstruction or resource withdrawal. Observers note that the appeal process, the initiation of related cases, the operationalisation of reparations, and the establishment of memory-preservation mechanisms are all vulnerable to political recalibration, particularly if public attention diminishes or if strategic interests favour a slower pace.

The legal framework for accountability exists: the domestic trial opened in 2022, convictions were delivered in 2024, and the 2022 MoU outlines clear responsibilities. What remains uncertain are the political, institutional and financial conditions necessary to see the process to completion. The next phase—appeals, related cases, operational reparations, witness protection, and memory preservation—will test whether Guinea’s political and judicial institutions can sustain a credible path to justice.

As Niang returned to The Hague, Guinean authorities reiterated their commitments. Survivors, lawyers, and civil society activists maintain that the credibility of these assurances must be judged not by diplomatic statements but by concrete actions in courtrooms, ministries, and communities. Sixteen years is a long time to wait for justice. If Guinea completes this process responsibly, it will not be because of international oversight, but because its own institutions held firm. If it falters, it will not be due to a lack of frameworks but to insufficient political resolve.

The massacre of September 28, 2009, remains a wound in the national memory. Whether it becomes a chapter of accountability or another entry in the ledger of unfulfilled justice depends on choices Guinea makes now—choices that will define how the next generation understands its past and the country’s capacity to confront it.

– global bihari bureau