Productivity Gaps Hinder Services-led Transformation

Geneva: Services are rapidly reshaping the economic landscape of the world’s least developed countries (LDCs), but this transformation has yet to translate into broad-based prosperity, better jobs or rising productivity, according to the Least Developed Countries Report 2025 released by UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD) on 10 February.

The report finds that services have become a central driver of growth and employment across LDCs, absorbing large numbers of workers as agriculture’s share declines. However, most of this expansion is concentrated in low-productivity and informal activities such as retail trade, personal services and subsistence livelihoods. While these sectors help sustain households, they generate limited income gains and weak development impact.

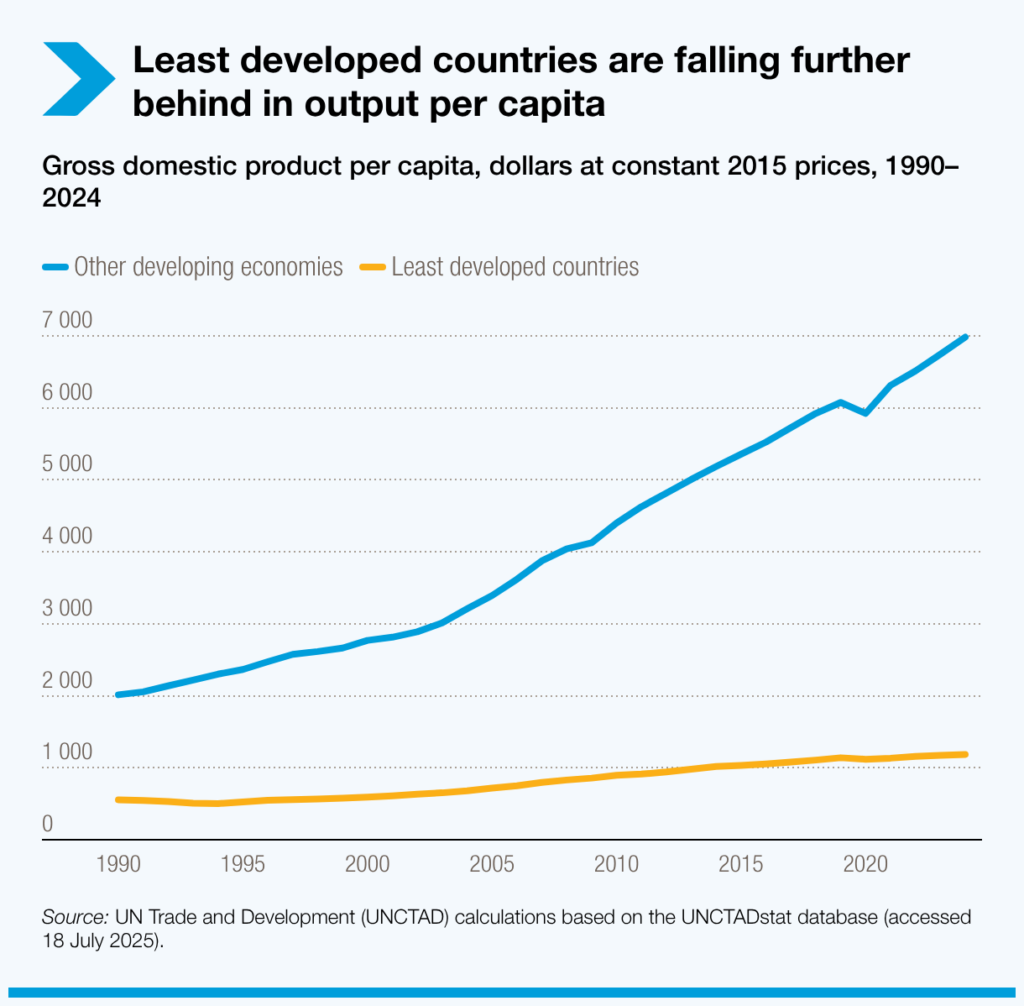

Despite the growing role of services, average per capita economic growth in LDCs remained sluggish in 2024, reinforcing concerns that services-led growth is not closing the income gap with more advanced economies. Output per capita in LDCs continues to fall further behind that of other developing and developed countries, reflecting deep structural constraints.

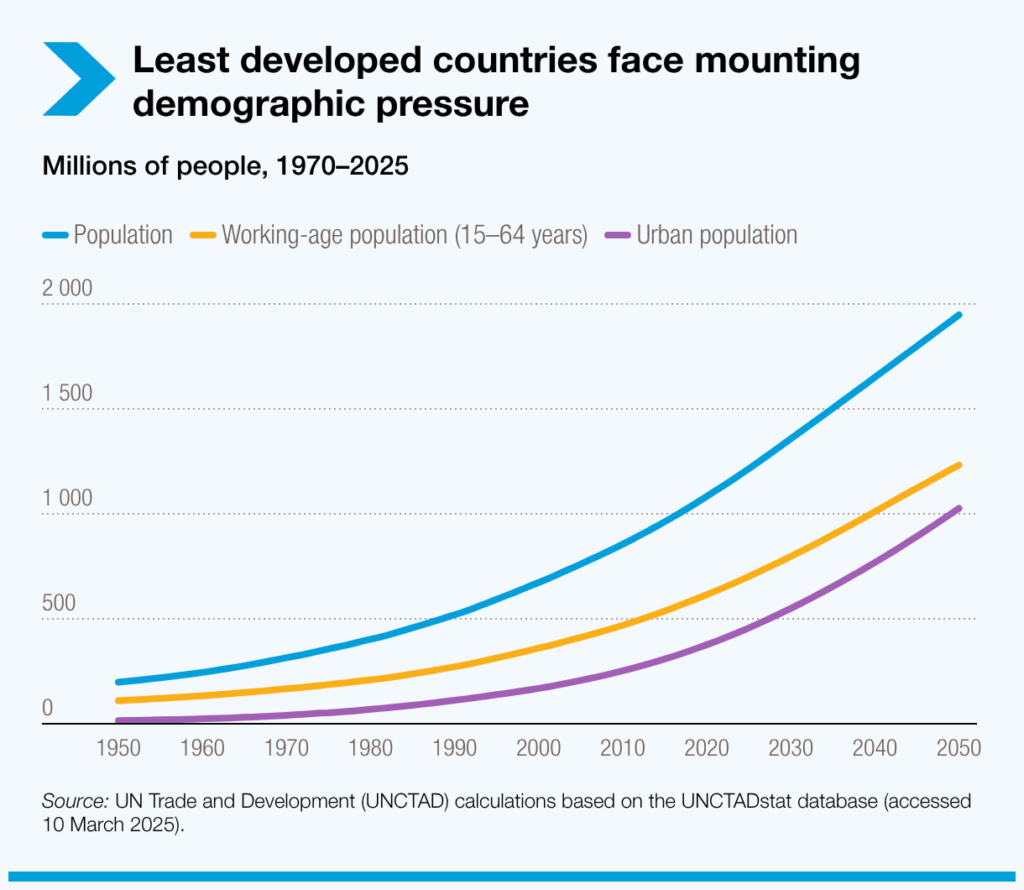

Employment creation has emerged as the defining development challenge. Between now and 2050, LDCs will need to generate jobs for around 13.2 million new labour market entrants every year due to rapid population growth and urbanisation. While services have absorbed much of this expanding workforce, job creation has not been matched by improvements in earnings. Working poverty remains widespread, highlighting the growing divide between having a job and earning a decent living.

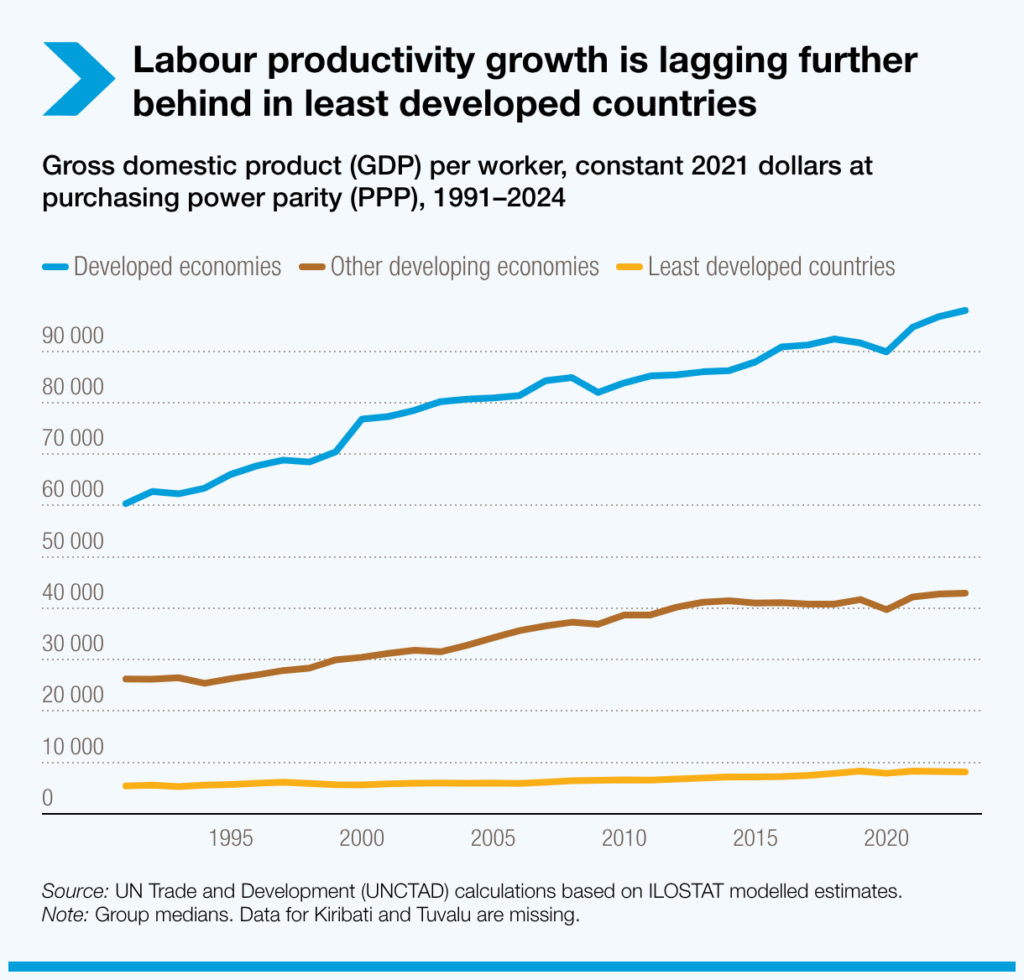

Low productivity remains the central obstacle limiting what services can deliver. Labour productivity in the average least developed country is estimated to be 11 times lower than in the median developed economy. These productivity gaps shape the type of services LDCs can realistically develop and export and restrict their ability to move into higher-value activities that support industrialisation and competitiveness.

UNCTAD stresses that services can contribute to structural transformation only when they are embedded in coherent national development strategies and supported by a favourable global environment. Without this, the expansion of services risks deepening marginalisation and reinforcing existing inequalities rather than reducing them.

Tourism and digital services illustrate both the potential and the limitations of current service-sector growth. Tourism accounts for about one-third of all services exports from least developed countries, making it their largest single export category in services. Yet high tourism revenues often fail to translate into large-scale job creation, stronger local value chains or lasting economic transformation because of weak infrastructure, limited domestic linkages and heavy reliance on imports.

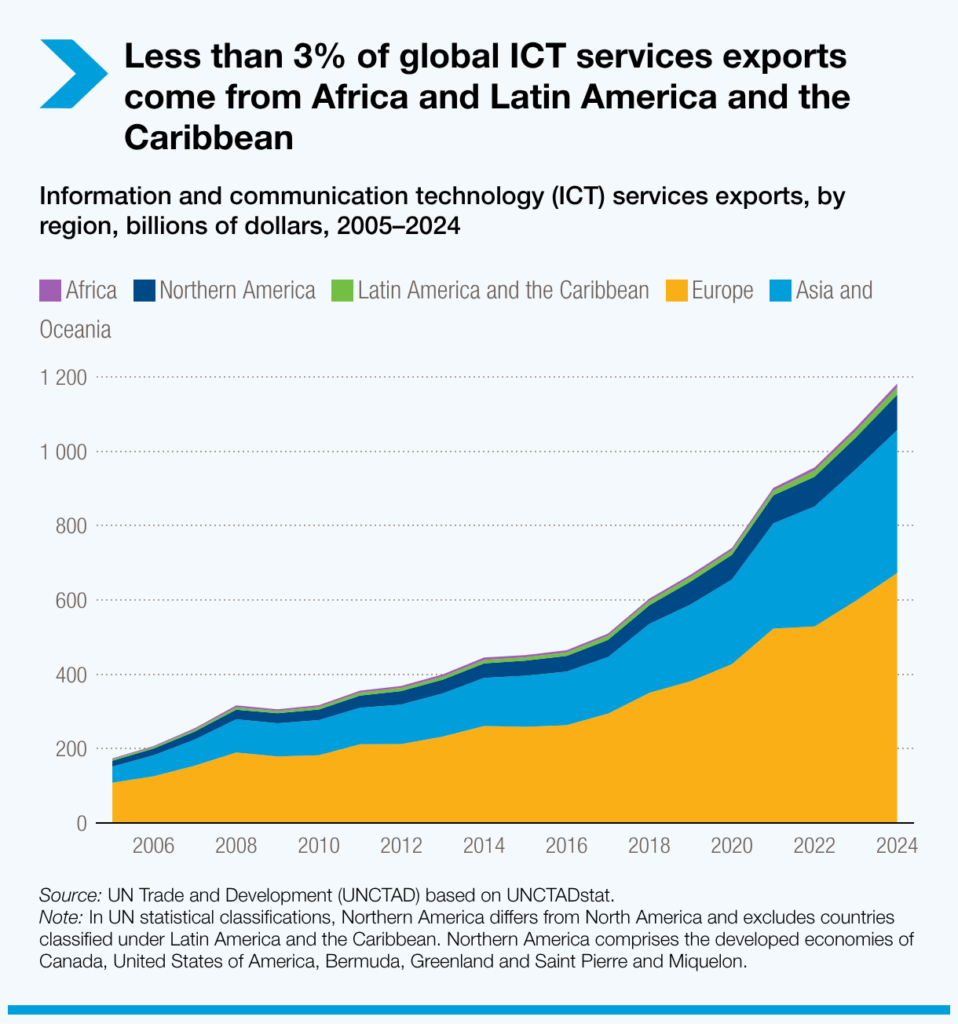

Digitally deliverable services are among the fastest-growing segments of global trade, but LDC participation remains extremely low. These countries account for just 0.16 per cent of global exports in digitally delivered services — the lowest share since records began. More broadly, less than three per cent of global ICT services exports come from Africa and Latin America and the Caribbean combined, underscoring the scale of the digital divide.

Exports of modern services remain concentrated in a small number of countries, reflecting persistent gaps in skills, connectivity and technological capacity. Digital skills have emerged as a decisive factor in determining whether services can shift toward higher productivity. Across LDCs, women are 42 per cent less likely than men to use mobile internet, while rural populations are 50 per cent less likely than urban residents to be connected.

Targeted national initiatives demonstrate what is possible but remain limited in scale. Rwanda’s Digital Ambassadors Programme has trained more than 5,000 young people to provide digital literacy in rural communities, while Malawi’s mHub supports women-led rural enterprises in accessing technology and markets. UNCTAD notes that such efforts need to be expanded substantially to match the size of the challenge.

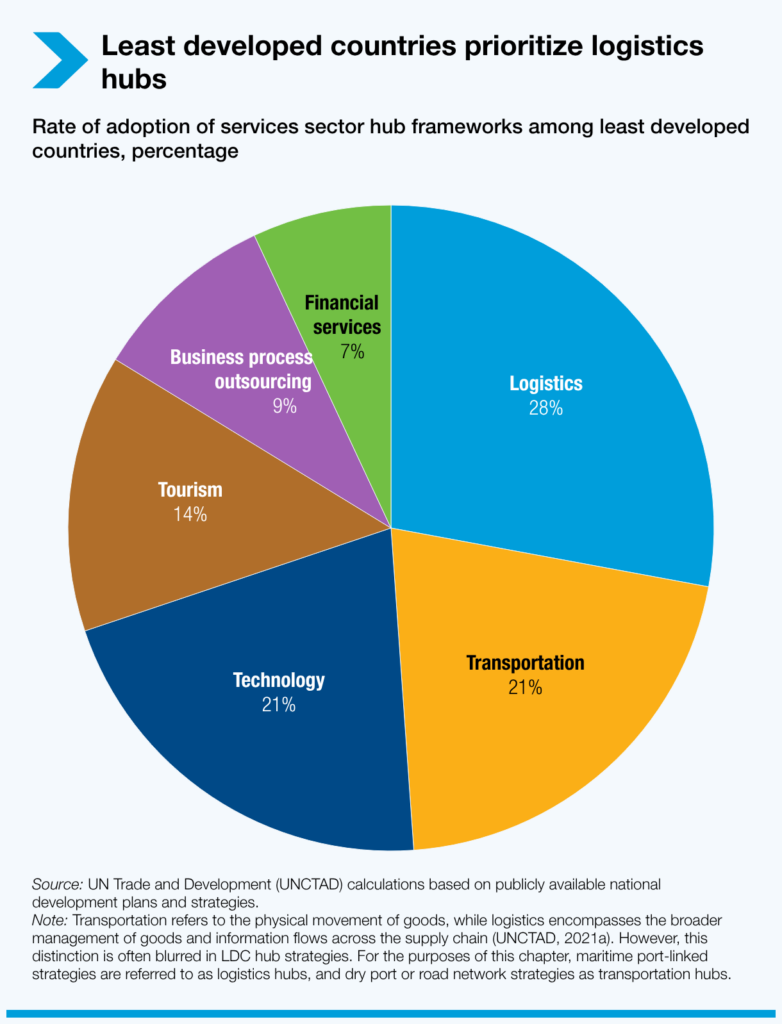

Many least developed countries are adopting “hub” strategies in sectors such as logistics, transport, technology and tourism to boost growth and exports. About 28 per cent prioritise logistics hubs, 21 per cent transportation hubs, 21 per cent technology hubs and 14 per cent tourism hubs, while smaller shares focus on business process outsourcing and financial services. Although these strategies can raise competitiveness and fiscal revenues, the report cautions that they often generate fewer direct jobs than expected and may increase risks related to debt accumulation, overcapacity and weak monitoring frameworks.

UNCTAD highlights that a better services policy depends on better services data. Persistent gaps in the availability and quality of statistics on the services sector continue to constrain effective policymaking and make it difficult to assess whether growth in services is delivering productivity gains and improved employment outcomes.

The report concludes that services are not a shortcut to development. For services to support industrialisation and competitiveness, they must raise productivity, build strong links with manufacturing and other productive sectors, and be backed by investments in digital infrastructure, reliable energy, education and skills. Closing digital divides, strengthening domestic capabilities and actively supporting services exporters — particularly small and medium-sized firms — are essential if LDCs are to compete in modern services markets and turn growth into inclusive development.

Regional cooperation can expand opportunities for services trade, but LDCs also require greater policy flexibility and stronger special and differential treatment at the global level. UNCTAD identifies major weaknesses in the LDC services waiver, including its voluntary nature, minimal preference margins and a mismatch between the preferences offered and the actual supply capacity of LDCs. To make the waiver effective, requests and offers must be updated to reflect current realities of global services trade, and new measures should be explored to extend meaningful preferences beyond their expiry in 2030.

Without targeted policies that link services expansion to productivity growth, skills development and industrial transformation, the report warns that service-led growth risks reinforcing existing inequalities rather than creating pathways to sustainable and inclusive development.

– global bihari bureau