AQUASTAT 2025: Stark Regional Gaps in Water Availability

733 Million Live in Countries with High or Critical Water Stress

Rome: Renewable water available per person has fallen by seven per cent over the past decade, according to new global figures released in the 2025 AQUASTAT Water Data Snapshot, published today by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations.

Rome: Renewable water available per person has fallen by seven per cent over the past decade, according to new global figures released in the 2025 AQUASTAT Water Data Snapshot, published today by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations.

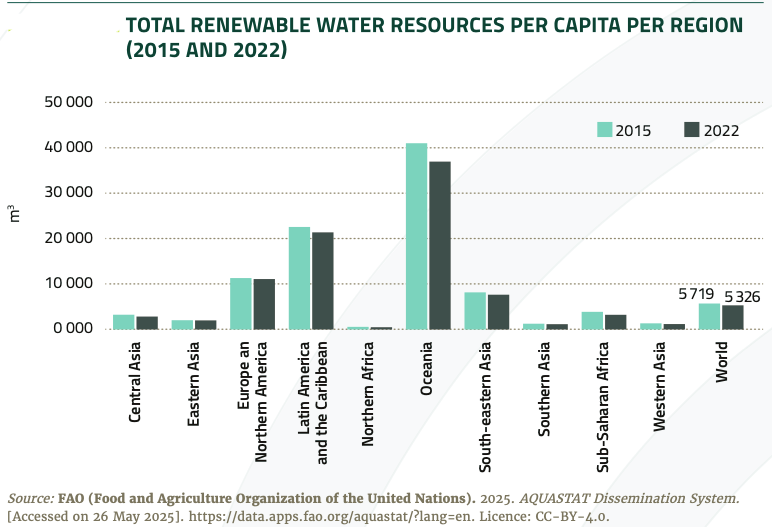

The decline reflects long-term reductions in freshwater endowments relative to population growth and comes as several regions are recording increasing withdrawals from already stressed river basins and aquifers. The snapshot, which compiles 2022 data gathered through FAO’s 2024 AQUASTAT cycle, places the fall in per-capita freshwater availability in a concrete numerical frame: global renewable resources now stand at 5 326 cubic metres per person, down from 5 719 cubic metres in 2015, an erosion that the report attributes to demographic pressures rather than abrupt hydrological loss.

Although the global decline is modest in percentage terms, the regional distribution of scarcity is markedly uneven. Northern Africa, with an estimated 565 cubic metres per inhabitant in 2022, sits at the bottom of the world’s freshwater ladder, followed closely by Southern Asia at 1 226 cubic metres and Western Asia at 1 252. Some regions with bigger endowments faced relatively steep declines: Sub-Saharan Africa saw a 17 per cent reduction in per-capita renewable resources since 2015, while Central Asia and Northern Africa each registered 12 per cent drops, Western Asia declined by 11 per cent and Oceania by nearly 10 per cent. The snapshot flags these changes without speculation, presenting them simply as part of the chronic imbalance between natural recharge and fast-rising populations.

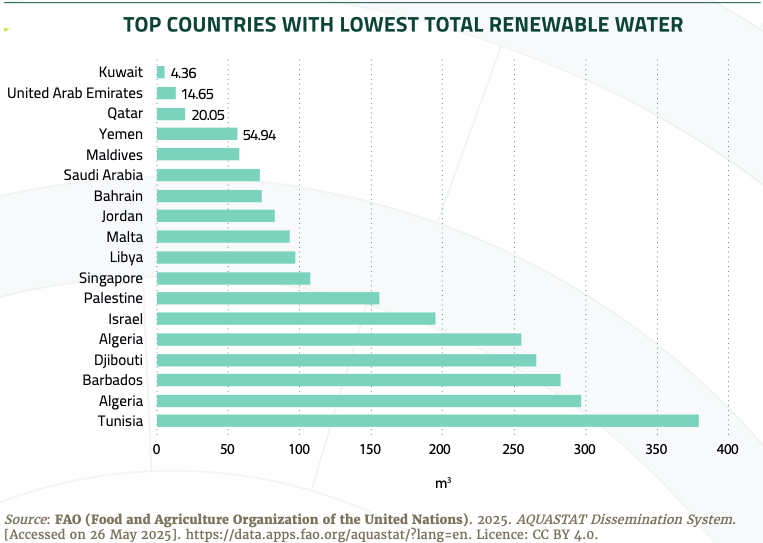

AQUASTAT’s compilation shows that freshwater scarcity is not a discrete event but a long-running structural condition. Several countries effectively operate without meaningful renewable supplies. The list of places facing the lowest per-capita water availability and the highest water-stress ratios reads like a catalogue of arid states heavily reliant on non-renewable groundwater and desalination. Kuwait’s total water withdrawals in 2022 amounted to nearly 38 times its renewable resources, resulting in a stress level of 3,851 per cent. The United Arab Emirates follows with 1510 per cent, Saudi Arabia with 974 per cent, Libya with 817 per cent and Qatar with 431 per cent. The set includes others where withdrawals routinely exceed renewable inflows, signalling deep reliance on fossil aquifers and imported “virtual water” embedded in food. More than 733 million people live in countries that fall into the high or critical stress categories — roughly a tenth of the global population.

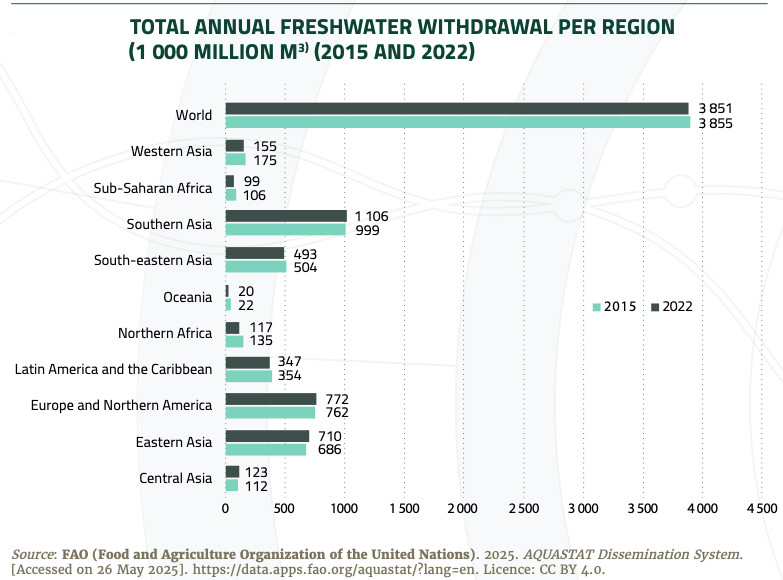

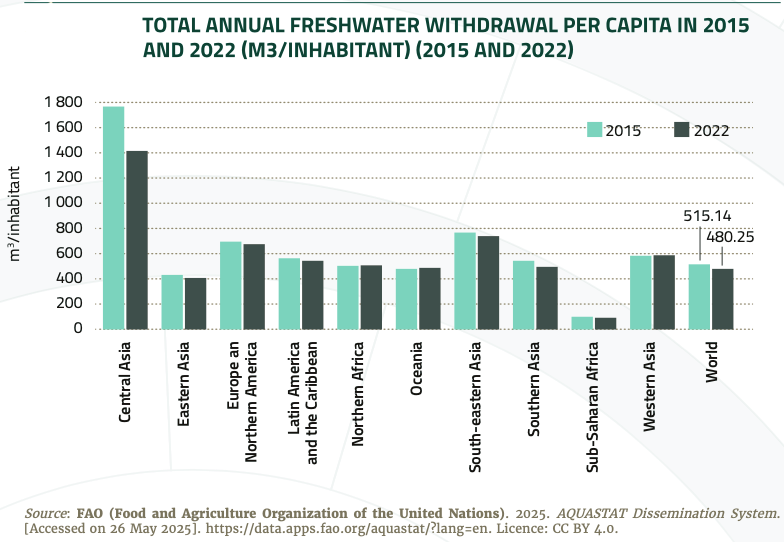

The snapshot’s data on withdrawals traces how the demand side contributes to this tightening squeeze. Globally, total freshwater withdrawals increased only marginally — by 0.1 per cent — between 2015 and 2022. Yet the calm surface masks considerable regional variation. Northern Africa posted the sharpest rise, up 16 per cent to 135 billion cubic metres. Western Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa each climbed in double digits, at 13 and 12 per cent, respectively. Central Asia, by contrast, recorded a nine-per-cent fall, and Eastern Asia, Southern Asia, Europe and Northern America registered reductions of three per cent or less. These shifts appear in the snapshot as recorded facts rather than interpreted trends, but their direction suggests that some of the world’s most water-scarce regions are the very places where extraction is increasing fastest.

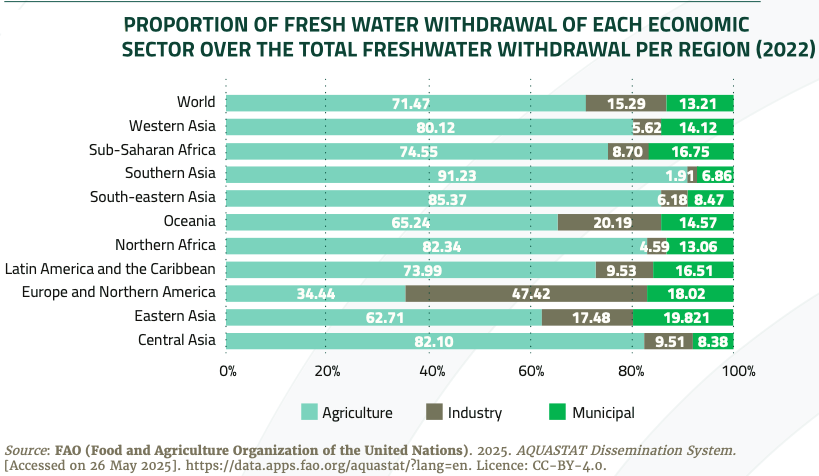

The breakdown of withdrawals by economic sector underscores agriculture’s overwhelming dominance. In 2022, agriculture accounted for 72 per cent of global withdrawals, followed by industry at 15 per cent and municipal uses at 13 per cent. Regionally, the proportions diverge sharply. Northern Africa’s agricultural share reached 99.6 per cent of total withdrawals, making it the region where irrigated fields absorb virtually all the water extracted. Southern Asia derived 70 per cent of its withdrawals from agriculture, Central Asia 57.6 per cent, and Western Asia 52.2 per cent. In high-income or temperate regions with more diversified economies, industry and municipal uses take larger slices, but nowhere do they overtake agriculture’s global dominance. The report notes that since 2015, global agricultural pressure on resources has eased only slightly — down 0.58 per cent — with more noticeable declines in Central Asia, Eastern Asia and Southern Asia, and steep increases in Oceania and Northern Africa.

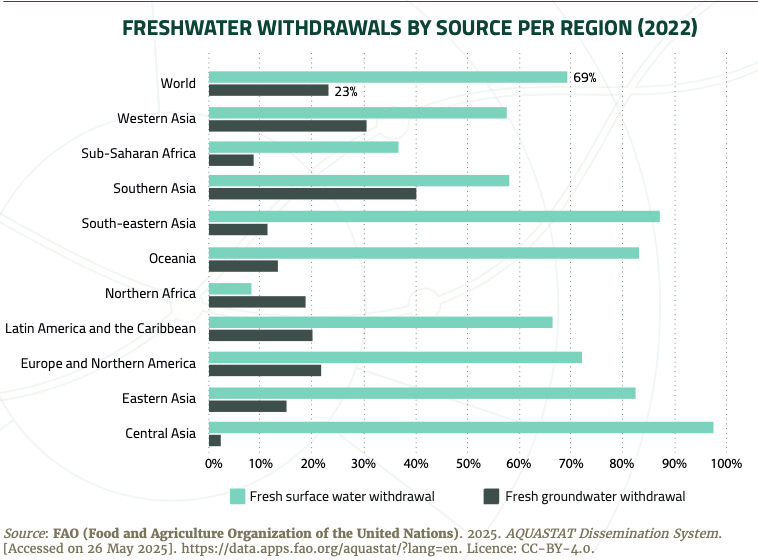

A further layer of scarcity emerges in the source of water withdrawn. Surface water remained the primary source in 2022, supplying about 69 per cent of global withdrawals. Groundwater accounted for around 23 per cent, while the remainder came from desalinated water and treated wastewater. Although these non-conventional sources represent only a small fraction globally, they are critical in some regions: Western Asia relies heavily on desalination, while treated wastewater makes a more significant contribution in Europe and North America. These figures help explain the exceptionally high water-stress ratios in certain Middle Eastern states, where desalination enables water use far beyond what local hydrology can support.

Irrigation statistics add another dimension to the pressures. In 2022, 23 per cent of global cultivated land was equipped for irrigation, up from 21.5 per cent in 2015. Southern Asia stood out with 46 per cent of its cropland under irrigation — the highest share globally — followed by Latin America and the Caribbean at 32 per cent and Central Asia at 25 per cent. Sub-Saharan Africa lagged far behind, with only 3.8 per cent of its cultivated land irrigated, a figure that underscores persistent infrastructure and investment gaps. Nationally, irrigation coverage exceeded 90 per cent in Bahrain, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Suriname and Uzbekistan, whereas 35 countries, mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa, had less than one per cent of their cropland under irrigation. These figures represent the uneven distribution of irrigation technology, but also illustrate why agriculture holds such a dominant share of water withdrawals in certain regions.

The snapshot also includes updates for the SDG indicators that FAO is responsible for tracking. Water-use efficiency — SDG 6.4.1 — improved globally from 17.47 dollars per cubic metre in 2015 to 21.50 in 2022. Gains were visible across economic sectors and most regions, with especially marked improvements in Eastern, Central and Southern Asia. Yet the report is careful to pair these efficiency gains with the water stress indicator — SDG 6.4.2 — which reveals the persistent pressure on limited resources. Global water stress stood at 18 per cent in 2022. Northern Africa registered a critical 121 per cent, meaning withdrawals exceeded renewable supplies once environmental flow needs were deducted. Southern Asia followed at 76.7 per cent, with high levels also seen in Central Asia (70.2 per cent) and Western Asia (65.1 per cent). Europe and Northern America (12.3 per cent), Latin America and the Caribbean (5.7 per cent), Oceania (3.2 per cent), South-eastern Asia (20.6 percent) and Sub-Saharan Africa (6.3 percent) remained in the low-stress category. Some regions, particularly Northern Africa, Western Asia and Oceania, saw stress intensify since 2015, while Central Asia, Eastern Asia, Europe and Northern America recorded slight improvements.

Hidden in the technical notes is an important reminder about the underlying data. AQUASTAT relies on annual questionnaires and a more detailed five-year survey sent to national institutions. For the 2024 cycle, 63 of the 153 questionnaires were returned — a response rate of 41 per cent — with Europe and Northern America achieving the highest participation at 65 per cent, followed by Central Asia, Eastern Asia and Northern Africa at 50 per cent each. Where national reporting was incomplete or outdated, FAO’s statistical system filled gaps using imputation methods, marking the resulting values accordingly in the dissemination platform. The snapshot emphasises that all reported data undergo validation in close consultation with national correspondents. This documentation does not diminish the credibility of the dataset but signals the limits of official reporting on global water resources, an area where many countries still lack the capacity to produce comprehensive water accounts.

The document also walks through the classifications underlying the dataset. Country groupings follow the United Nations Statistical Division’s M49 standard, and the values for regional aggregates are calculated carefully to avoid double-counting. For SDG 6.4.1, indicators are derived from aggregated values as if calculated for a single country. For SDG 6.4.2, a weighted mean is applied, incorporating internal renewable water resources and adjusting for environmental flow requirements at the regional level. Such methodological notes are rarely the focus of public discussion but shape how global and regional scarcity are represented.

The AQUASTAT system itself, as described in the report’s overview pages, extends beyond the core database. The portal compiles metadata, country profiles, river-basin profiles, maps, spatial datasets and information on dams, reservoirs and water-sector institutions. This broader infrastructure enables users — from UN agencies to NGOs, ministries and private companies — to interpret the status of water resources within a consistent statistical frame. The 2025 snapshot contributes to this by presenting more than ten high-level indicators through charts, maps and region-specific figures, all derived from the most recent year available: 2022.

Taken as a whole, the new AQUASTAT Water Data Snapshot presents a world in which freshwater scarcity is a quantifiable, mapped and increasingly uneven burden. The global averages mask sharp divides: some countries operate under resource conditions comparable to chronic overdraft, made viable only through desalination or the rapid depletion of ancient aquifers, while others maintain low levels of stress but face persistent competition between cities, farms and industry. The report offers no interpretation beyond the data itself, but the numbers describe a global system where more than 700 million people now live in countries withdrawing more water than their renewable endowments provide each year, and where most regions have seen their natural per-capita freshwater availability decline within a decade. In the measured language of the snapshot, these trends represent the hydrological baseline against which future planning, monitoring and international cooperation must operate.

– global bihari bureau