New federation to empower India’s smallest businesses

YEFI targets 10,000 members, $1B valuation by 2030

Pune: While the world marked Global Entrepreneurship Week 2025 with the ringing theme “Together We Build” across more than 200 countries, a modest hall in Pune quietly wrote a new line in India’s entrepreneurial story. On this day, today, the YouthAid Entrepreneurs Federation of India (YEFI) came into being, an independent body which claimed to be created exclusively for the country’s countless micro-entrepreneurs who stitch, weld, pack, and sell from village courtyards, small-town workshops, and urban bastis.

“In today’s changing India, such a federation is not optional; it is necessary for last-mile inclusion, dignity, and economic justice,” said Mathew Mattam, taking the chair as YEFI’s first Chairman. He described YEFI as a bridge that will connect grassroots entrepreneurs with government schemes, banks, Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) partners, digital platforms and investors, while promoting standardisation, quality, branding and ethics so micro-businesses can scale sustainably and seed the next generation that will shape India’s future.

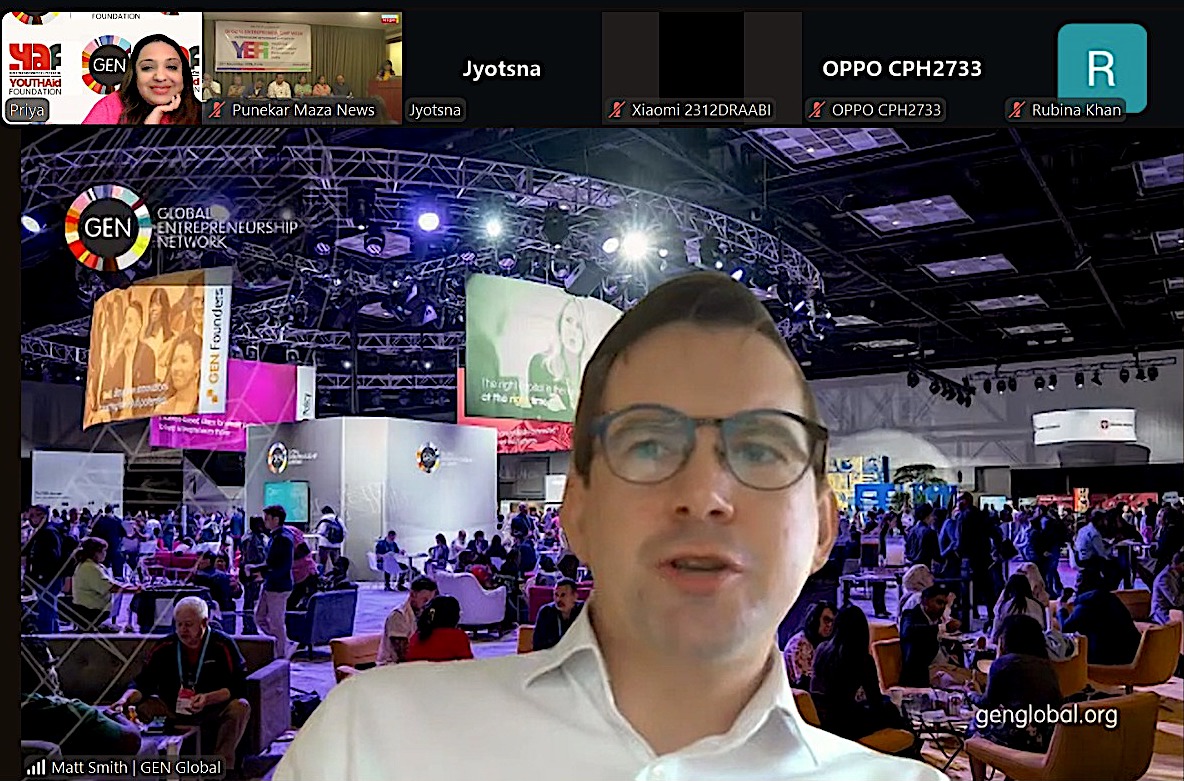

From London, Matt Smith, Vice-President of Global Entrepreneurship Network UK, joined the launch live. “Ecosystem building is not just a buzzword,” he told the room. “It is the vital infrastructure that sustains an economy and empowers a country’s future. For GEW 2025 to mean anything lasting, we must reach far deeper into the grassroots – those often-overlooked micro-entrepreneurs who form the bedrock of local economies. My heartfelt congratulations to YouthAid Foundation for launching YEFI at exactly the right moment to drive this localised, crucial momentum.”

Priya Kothari, speaking from Virginia as International Director of YouthAid Foundation and Executive Director of WUST Foundation, carried the vision further: the movement must touch every state in India before stepping confidently onto the global stage. “Focused mentorship, resources, digital and financial literacy,” she said, “will unlock the potential of micro-entrepreneurs and transform local livelihoods into powerful contributors to the global economy.”

The doors opened with strict conditions – only enterprises at least two years old, with audited accounts, filed income-tax returns, and a minimum annual turnover of Rs 5 lakh may enter. More than 2,400 micro-businesses are reportedly scrambling to finish their audits, but six made it first and were inducted as founding members: Sarthak Enterprises, AgroZee Organics Pvt Ltd, YouthAid Global Services Pvt Ltd, VK Control Systems Pvt Ltd, Shital Enterprises, and Agrotech Farmer Produce Company. Together they bring an audited annual turnover of Rs 22 crore, 105 jobs – 73 per cent of them held by women – and every rupee earned without grants or charity.

The board is chaired by Mathew Mattam and includes four practising entrepreneurs, social activist Jyotsna Bahirat, and academic Professor Ujjwal Anu Chowdhury. Vicky Kalbande from Amravati could barely contain his excitement: “Making YEFI a social unicorn by 2030 is our main goal, and I will take my business from Amravati to the world under this banner.” Bapu Narute, grinning, sealed the moment: “First anniversary, Dubai, 22 November 2026. It’s done.”

The phrase “social unicorn” might sound like jargon, but it carries a clear promise: a billion-dollar valuation built from the ground up, with profits and control staying inside the community instead of vanishing into venture funds. Any surplus the members or the federation earn will flow back into cheaper credit, bulk buying, training and shared platforms – an e-commerce portal for all members, an export desk, a peer-mentorship system where seasoned entrepreneurs guide newcomers as “Uday Gurus”, and delegations across the Global South.

Far from being a fantasy, this model already thrives in several corners of the world. Bangladesh’s Grameen Bank family remains owned by the nine million rural women who borrow from it and has long passed $2.5 billion in combined value. Spain’s Mondragón Corporation generates €11 billion a year, yet every one of its 80,000 worker-owners retains one vote and a direct share. In 2022, Patagonia handed ownership to a purpose trust that channels all non-reinvested profits into climate defence. Chile’s Betterfly became Latin America’s first certified B-Corp unicorn by turning employee wellness perks into millions of donated meals and health services. Kenya’s nationwide SACCO movement, entirely member-owned, now controls assets worth over $12 billion and serves fifteen million small-scale entrepreneurs and farmers. These are living proof that billion-dollar scale and grassroots ownership can coexist – and YEFI intends to write the Indian chapter.

Prof Chowdhury explained that the absence of any chamber of commerce dedicated exclusively to micro-entrepreneurs, and the need to harness their immense potential is exactly why YEFI was launched. He then outlined the growth path, starting with the Hyderabad YES Summit in February 2026 – a key milestone event in the federation’s calendar, supported by the Telangana government incubation cell. This summit builds on the legacy of the original International Youth Employment Summit (YES) held in Hyderabad in December 2003, India’s first such gathering, which drew over 1,000 delegates from 22 countries in South Asia and Southeast Asia. Inaugurated by then-President A P J Abdul Kalam and attended by Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee at the valedictory, that event focused on youth employment through themes like renewable energy, rural development, water and sanitation, HIV/AIDS awareness, skill development, self-employment, and literacy as a pathway to jobs. Andhra Pradesh presented a draft youth policy there for global input, marking a pivotal moment for grassroots innovation in the region. Now, two decades later, YEFI plans to send 500 members to the 2026 edition, aiming for a combined turnover crossing Rs 50 crore; over 1,000 members and Rs 100 crore by the Delhi summit in November 2027; and, by the fifth anniversary in November 2030 – coinciding with the close of the UN Sustainable Development Goals – 10,000 members, Rs 1,000 crore audited turnover, more than 100,000 jobs, and a valuation of Rs 10,000 crore (USD 1 billion), becoming India’s first ever social unicorn.

Yet anyone who has watched India’s micro-enterprise landscape knows the road is littered with potholes. The country’s microfinance sector, which once looked like the perfect ladder out of poverty, is today facing its worst crisis since the 2010 Andhra Pradesh meltdown. Gross NPAs have doubled to around 16 per cent, over-indebtedness is rampant, and borrowers in states like Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Uttar Pradesh are juggling four or five loans just to stay afloat. Interest rates still hover between 22 and 30 per cent – justified by high operating costs in rural areas, but crushing for a woman earning ₹15,000 a month. Coercive recovery practices, multiple lending, weak credit bureaus and the arrival of unregulated digital lenders have together created what the RBI itself calls a “vicious cycle”. In the first half of 2025, fresh lending slowed sharply as MFIs focused on cleaning up old portfolios, and several state governments brought in ordinances that froze collections entirely in the name of protecting borrowers.

This is the very storm YEFI is sailing into. Its insistence on audited accounts, two-year track records and a minimum turnover is designed to keep out the chronically over-indebted and to build a membership that banks can actually trust. By creating a federation-owned credit pool and bargaining collectively, it hopes to bring down the cost of capital far below today’s punishing rates. Whether that promise holds will depend on three hard realities: how many of those 2,400 waiting enterprises actually clear the audit hurdle, how quickly banks and CSR arms recognise the federation as a credible counterparty, and whether the internal discipline survives when growth tempts shortcuts – the same temptation that has wounded the larger microfinance industry.

The good news is that India’s regulators and policymakers are not standing idle amid this turmoil. Over the past two years, a wave of reforms has aimed to strike a balance between protecting vulnerable borrowers and keeping the sector viable for lenders. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been at the forefront, building on its 2022 harmonised framework that redefined microfinance loans as collateral-free credit to households earning up to ₹3 lakh annually, with total indebtedness capped at ₹3 lakh (tightened to ₹2 lakh by self-regulators in January 2025). In February 2025, RBI revised risk weights under Basel III, assigning a lower 75% risk weight to qualifying microfinance loans under the Regulatory Retail Portfolio (down from 125% for consumer credit), freeing up bank capital and encouraging more lending – a move that has already helped entities like Small Finance Banks, such as Bandha,n reduce delinquencies to 3.8%. From October 2024, all lenders must issue a Key Facts Statement detailing rates, fees, and terms, boosting transparency and curbing hidden charges. Self-regulatory bodies like MFIN and Sa-Dhan, recognised by RBI since 2014, have stepped up too, limiting borrowers to three MFIs (from four), mandating quarterly pricing reviews, and targeting 50% PAN seeding for accounts by March 2025 to improve underwriting. In June 2025, RBI Deputy Governor M. Rajeshwar Rao called for “soul-searching” reforms, urging ethical practices and better risk models to break the cycle of over-leverage and coercion. These central measures are complemented by government schemes like Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), which hit 550 million accounts by May 2025 (56% women-owned, with ₹2.5 trillion in deposits), and MUDRA Yojana, which added 80 lakh new women clients in 2022-23 alone, totalling 6.64 crore. In August 2025, the microfinance industry sought ₹200 billion ($2.2 billion) in credit guarantee support from the government – similar to the ₹75 billion pandemic-era scheme – to counter high borrowing costs and a 16.7% portfolio contraction, signalling a push for more liquidity.

At the state level, the response has been even more immediate and varied, creating a patchwork of protections that sometimes clash with national rules but underscore the urgency. Karnataka’s Micro Loan and Small Loan (Prevention of Coercive Actions) Bill, 2024, imposes up to 10 years in jail and ₹5 lakh fines for coercive tactics, following reports of borrower suicides and public backlash against unregistered agents – a law that froze collections in parts of the state and contributed to the NPA spike. Tamil Nadu’s Money Lending Entities (Prevention of Coercive Actions) Act, 2025, bans harassment outright and discharges borrowers from unlicensed MFI debts, including interest, while mandating transparent pricing. Andhra Pradesh, scarred by its own 2010 crisis, has become a model with post-2011 reforms emphasising borrower rights and transparency. These state interventions, while disruptive in the short term (e.g., loan originations plunged 42% by December 2024), have curbed abuses and forced lenders to rethink practices. Yet challenges linger: the Joint Liability Group (JLG) model is fraying due to urban migration and shifting borrower profiles; 60% of lending remains concentrated in just five states (Bihar, Tamil Nadu, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Karnataka), leaving the Northeast and central India underserved; and low literacy rates (below 60% in eastern states) hinder digital adoption. Election-year debt waiver fears in Bihar, where 15% of the portfolio sits, add uncertainty, while external shocks like 2025 floods and heatwaves have hammered repayment capacity.

US-based media and entrepreneurship evangelist Dr Tausif Malik welcomed the initiative and the power of the social-unicorn concept driving it.

The launch deliberately confronts the acute invisibility of grassroots businesses – especially those run by women in villages, small towns and urban slums – in mainstream media and business discourse. Democratising grassroots entrepreneurship, the founders insist, means changing the script: making it normal and possible for a young woman in a basti, a farmer’s son, or a first-generation diploma holder in a small town to build and own an enterprise with dignity and support.

Whether YEFI becomes the revolutionary rise its founders envision, or another cautionary tale in a sector that has seen too many, now depends on execution. For now, in a country that celebrates its unicorns loud and shiny, a quieter, more stubborn one has taken its first steps.

– global bihari bureau