Lok Sabha Sees High-Stakes Debate on Voting Systems

Roll Revisions and EVM Credibility Shape Political Debate

New Delhi: The Lok Sabha’s debate on electoral reforms today became a rare moment when long-running disagreements over India’s electoral machinery surfaced simultaneously and in full public view. What was listed on the agenda as a discussion on reforms expanded into a wide-ranging examination of how the Election Commission exercises its Constitutional powers, how political parties interpret the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) now underway, and how India’s voting systems have evolved across seven decades. What made the session unusual was not only the breadth of issues raised but the way they converged at once—voter-roll revision, the credibility of Electronic Voting Machines (EVMs), and the institutional independence of the Commission—turning a scheduled debate into a comprehensive airing of competing visions of electoral legitimacy.

Leader of the Opposition Rahul Gandhi framed the debate around concerns of institutional trust and administrative integrity. He said the Special Intensive Revision had generated apprehension among voters and administrators in several states, warning that large-scale deletions could have consequences beyond routine updating. Gandhi also questioned whether local officials were under pressure and suggested that confidence in EVMs had eroded, stressing that the electorate’s trust in the process could not be restored without the Election Commission’s visible independence. His interventions were punctuated by frequent interruptions and slogans from treasury benches, reflecting both the stakes involved and the highly charged atmosphere of the House.

Gandhi’s critique focused on procedural risks and the broader symbolic trust in elections. He argued that while the legal framework existed, the implementation of SIR needed oversight, and that perceived irregularities could delegitimise results. Opposition members repeatedly sought clarification on the scale and impact of deletions, particularly in constituencies where margins were tight. The Leader of the Opposition also raised the issue of verification of EVMs and Voter Verifiable Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT)s, linking technological credibility to voter confidence.

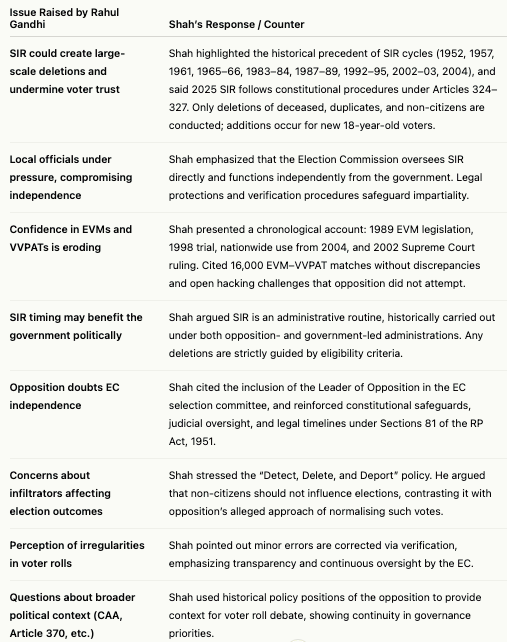

In response, Union Home Minister Amit Shah systematically addressed each concern raised by Gandhi, countering points with historical and procedural detail. To Gandhi’s apprehensions about deletions, Shah emphasised that SIR had been carried out in multiple cycles since 1952—regardless of which party held power—and that the current revision adhered strictly to constitutional provisions under Articles 324–327, as he stated on the floor of the House. He reiterated that the deletion of names occurs only in cases of death, duplicates, or non-citizenship, while eligible 18-year-olds are automatically added. By doing so, Shah positioned the revision as an administrative correction rather than a politically discretionary act.

When Gandhi questioned the independence of local officials, Shah argued that the process is monitored directly by the Election Commission, which functions as a constitutional body independent of the government. He cited Articles 325 and 326 to underscore that voter eligibility criteria are constitutionally mandated, and Article 327 to show the EC’s authority to make legal recommendations. Shah’s counter framed administrative rigour as the mechanism ensuring impartiality, and highlighted that any errors are subject to verification and correction by constitutional procedures.

Regarding EVM trust, Shah rebutted Gandhi’s claims by tracing the machines’ legal and operational history. He reminded the House that EVMs were introduced under legislation when the opposition was in power, trialled across multiple states in 1998, adopted nationwide in 2004, and validated by a 2002 Supreme Court Constitution Bench ruling. Shah added that approximately 16,000 EVM–VVPAT matches had been conducted without discrepancy, and that open public hacking challenges issued by the EC had not been attempted by opposition parties. By systematically walking through dates, court rulings, and verification exercises, Shah countered Gandhi’s suggestion of technological unreliability with officially reported parliamentary figures.

Shah also rebutted Gandhi’s broader political framing, which suggested SIR could alter electoral outcomes in favour of the government. He argued that voter-roll updates were periodic administrative routines, not instruments of political advantage. He further asserted that opposition concerns over voter deletions ignored the fact that past SIRs were conducted under opposition-led governments, including during the 1950s, 1960s, and early 2000s. By juxtaposing historical precedent with current procedures, Shah emphasised continuity and institutional stability.

The sharpest analytical contrast between the two leaders lay in how they framed the same facts. Gandhi presented the revision as a potential point of failure for institutional trust, highlighting perception, autonomy, and local discretion. Shah presented it as a structured, legally sanctioned, and verifiable administrative exercise. Each leader cited historical revisions, legal provisions, and technical processes, but the implications they drew were contrasting—one focused on safeguarding confidence, the other on maintaining procedural correctness and constitutional mandate.

Shah’s response extended to opposition claims about infiltrators and electoral security. While Gandhi questioned the deletion criteria and scale, Shah explained that the government’s policy is to “Detect, Delete, and Deport” non-citizens from the voter list, framing this as necessary for the protection of the electoral process. He juxtaposed this with what he described as opposition policy: normalisation and formalisation of infiltrators. In the House, this led to interruptions and protests from opposition benches, illustrating how the technical debate over SIR intersected with wider political and security narratives.

Electronic Voting Machines became another axis of disagreement. Gandhi said public confidence had eroded and argued for a verifiable system. Shah responded with a chronological account: the 1989 law introducing EVMs, trials from 1998, nationwide use from 2004, and the 2002 Constitution Bench ruling affirming their validity. He cited “around sixteen thousand” EVM–VVPAT matches without discrepancies and noted that open hacking challenges issued by the Commission had not attracted opposition participation. This line of reasoning underscored the government’s emphasis on continuity and judicial endorsement, while the opposition’s remarks underscored concerns around perception, transparency and the interpretive space around technology in elections.

Breakdown of Shah’s Rebuttals to Rahul Gandhi in the Lok Sabha

The debate also encompassed the composition and independence of the Election Commission. Shah noted that the government had expanded consultation by including the Leader of the Opposition in the selection of Election Commissioners, contrasting it with earlier practice where only the Prime Minister decided appointments. Opposition members argued that this measure was insufficient and called for a broader, independent collegium.

The House environment added another dimension to the debate. Frequent interruptions, overlapping slogans, and attempts by Gandhi to interject during Shah’s responses made the proceedings fragmented. These dynamics mirrored the substantive tension over electoral legitimacy and trust, suggesting that parliamentary behaviour itself was a lens through which confidence in democratic institutions was being contested.

Shah linked the SIR debate to a broader political context, citing opposition stances on Article 370, the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, the Ram Temple, surgical strikes, air strikes, and the law on triple talaq. He argued that these positions illustrated patterns of opposition policy that intersected with electoral and governance debates. Gandhi and opposition members questioned the relevance of such references, but the inclusion reflected how electoral reform debates often merge with wider political narratives in Parliament.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi later posted on X, commending Shah’s speech as “outstanding” and noting that it highlighted diverse aspects of India’s electoral process while exposing Opposition claims. The post reinforced the government’s framing outside Parliament and ensured the messaging continued into the broader public discourse.

Historically, voter-roll management in India has evolved over seven decades. The first rolls were compiled for the 1951–52 election, a massive exercise in a newly independent country. Subsequent revisions in the 1950s and 1960s addressed errors, deaths, and changes in residence. By the 1980s and 1990s, increasing urban migration and mobility prompted further revisions. Photo identity cards and computerisation in the 1990s and 2000s improved accuracy but introduced new administrative complexities. In this context, the 2025 SIR represents continuity rather than a novel intervention, though its proximity to the 2026 election cycle increases political significance.

As reported by Union Home Minister Amit Shah in Parliament, the 2025 SIR involves verification of over 7.24 crore electors, identification of approximately 36 lakh electors permanently shifted, and addition of first-time voters turning 18. These figures underscore the administrative scale of the exercise rather than any political intent. The opposition has indicated it will continue seeking independent scrutiny, signalling that parliamentary debate is only one stage of a larger contest over electoral trust ahead of the 2026 cycle.

– global bihari bureau