Plant Lichens

Pune: In the green forests of the Western Ghats, scientists have discovered a new lichen called Allographa effusosoredica, showing how tiny fungi and algae work together to help the environment that local people depend on.

A team from the MACS-Agharkar Research Institute, an institute under the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, led by Ansil P. A., Rajeshkumar K. C., Sruthi O. P., and Bharati O. Sharma, made this find, marking the first time an Indian lichen in the Allographa group has had its genetic code studied. For a local farmer near the Western Ghats, whose crops grow thanks to healthy soil and insects, this finding highlights the small creatures that keep her fields thriving, connecting her life to nature’s balance.

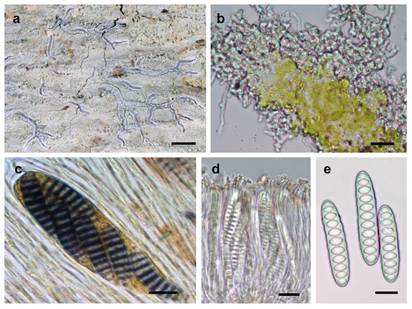

The study, funded by the Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF) through a project called “Unravelling the symbiosis of algal and fungal partners in lichen family Graphidaceae and Parmeliaceae from the Western Ghats through polyphasic taxonomic approach and ecological studies,” used traditional and modern tools to learn about this lichen. Allographa effusosoredica is a thin lichen with powdery spots called soredia and a special chemical, norstictic acid, which is rare compared to similar lichens. The team looked at its shape, chemicals, and genetic code, using tools to read parts of the fungus’s DNA—called mitochondrial small subunit (mtSSU), large subunit (LSU), and RNA polymerase II second largest subunit (RPB2)—and a part of the algae’s DNA called internal transcribed spacer (ITS). They found the algae partner is a type of Trentepohlia, similar to Trentepohlia cf. arborum, which helps us know more about algae in tropical lichens.

The team learned that Allographa effusosoredica is closely related to another lichen, Allographa xanthospora, but looks like Graphis glaucescens, raising questions about how lichens in the Graphidaceae family evolved. This lichen is the 53rd Allographa found in India and the 22nd in the Western Ghats, showing how many different plants and animals live in this area. The study says more research is needed to learn about India’s lichens, especially in places like the Western Ghats.

Lichens are like tiny teams where a fungus gives shelter and an algae partner makes food with sunlight. They help nature by making soil, feeding insects, and showing if the environment is healthy. For the local farmer, lichens keep the soil good for growing crops and support insects that help her plants grow, helping her family earn a living. This discovery could guide ways to protect the Western Ghats, keeping it a place where farmers can work.

Other countries are also studying lichens to help their environments. In Costa Rica, the La Selva Biological Station, run by the Organization for Tropical Studies, checks lichens to see if forests are healthy, working with farmers like those in the Western Ghats. In Australia, the Australian National Herbarium uses genetic tools to study lichen partnerships, helping to understand nature, much like the Pune team’s work. In Brazil, the University of São Paulo studies lichens in the Atlantic Forest to learn how they help the soil, giving ideas for protecting India’s forests.

For a local schoolteacher in Pune, this discovery is a chance to teach students about nature. “This shows how lichens in our forests help keep our environment healthy,” she said, hoping it will encourage students to care about the Western Ghats. The MACS-Agharkar team’s work helps us understand lichens and why they matter for India’s nature. From the Western Ghats to places like Costa Rica, Australia, and Brazil, this discovery shows how science can help people protect the environment they depend on.

– global bihari bureau