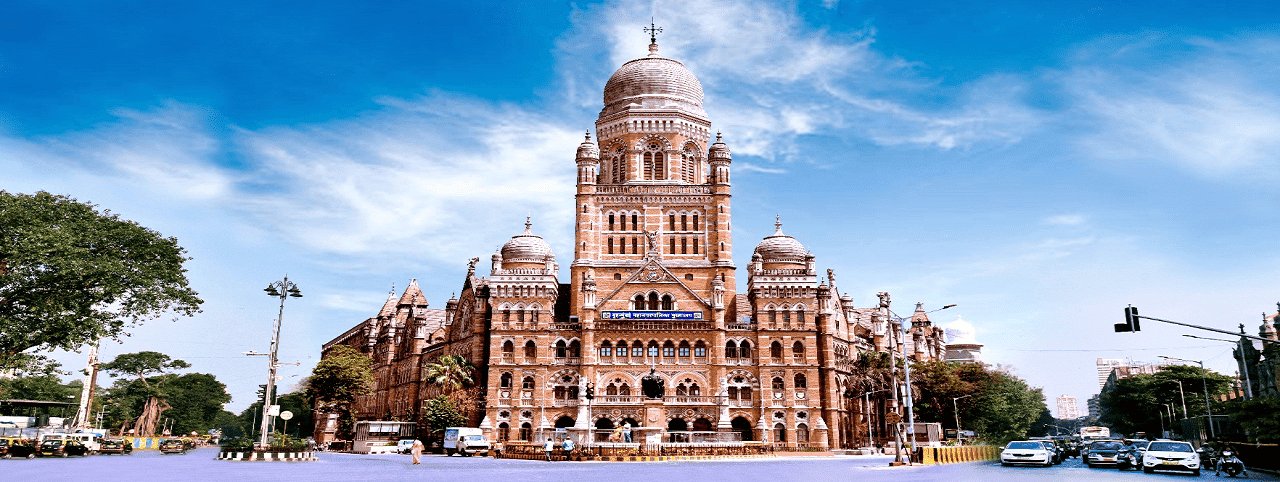

The BMC Headquarters in Mumbai

By Vinod Raghavan*

By Vinod Raghavan*

BMC 2026: Alliance Cracks, Identity Politics and the Mayor’s Race

Corporate, Identity Clash Shapes Mumbai Civic Battle

Mumbai: Mumbai is heading into one of its most politically charged civic contests in recent memory as voters prepare to elect a new Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) after a prolonged interregnum. The January 15 election is unfolding amid open political hostility, sharpened ideological contrasts and unusually blunt rhetoric, transforming what is normally a ward-level civic exercise into a proxy battle for Maharashtra’s future political direction. At stake is not only control of India’s richest municipal body but also narrative dominance in the country’s financial capital, whose annual budget stands at approximately ₹74,427 crore and whose administrative decisions affect more than two crore residents.

The election comes after the BMC has functioned without an elected house since 2022, governed instead by administrators. This gap has coincided with mounting civic pressures, from infrastructure stress and climate-related flooding to everyday concerns over roads, sanitation, housing and public health. The return of corporators is therefore being framed by all sides as a restoration of democratic accountability, even as the campaign itself has grown increasingly polarised.

A look back at the last BMC election in 2017 underscores how dramatically the terrain has shifted. That election delivered a fractured verdict, with the undivided Shiv Sena emerging as the largest party with 84 seats, closely followed by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) with 82, while the Indian National Congress secured 31. Despite the BJP’s rapid rise in Mumbai at the time, the Shiv Sena retained control of the civic body, reinforcing its long-standing claim over the city. Since then, however, the political order has been upended by the split in the Shiv Sena, the division of the Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) and the reconfiguration of alliances at the state level.

The current contest is widely seen as being fought on two intersecting and competing axes. On one side is a bitter struggle between former ideological partners within the broader Hindutva space, now estranged and attacking each other in public. On the other hand is the revival of the “son of the soil” or Marathi Manoos plank, led by the coming together of Uddhav Thackeray and Raj Thackeray. Their reunion has reintroduced a sharp identity-based appeal into the campaign, pitched as a fight to protect Mumbai’s character and autonomy. Amid this noisy confrontation, sections of the Muslim community are being described by political observers as watching the unfolding drama from a distance, weighing their options in a fragmented contest rather than aligning uniformly with any single formation.

At the centre of the ruling alliance’s campaign is Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis, who has left little doubt about the BJP’s ambition to capture the mayor’s post in the cash-rich corporation. He has publicly projected confidence that the BJP will hoist its flag over the BMC and has dismissed the political relevance of the reunited Thackeray brothers, arguing that the so-called Thackeray brand no longer resonates and that electoral battles will be decided by what he calls the Modi brand. These remarks have further inflamed tensions, prompting a more aggressive response from the Thackeray camp.

Uddhav and Raj Thackeray, along with the next generation of leadership represented by Aaditya Thackeray and Amit Thackeray, have taken to the streets and public platforms with renewed intensity. Their messaging frames the election as a struggle to save Mumbai from what they describe as corporate capture, explicitly naming major conglomerates and alleging that the BJP acts as a conduit for corporate interests. This line of attack has added a class and economic dimension to a campaign already thick with ideological and identity-based claims.

The ruling Mahayuti alliance itself reflects internal contradictions that have spilt into the civic arena. While the BJP heads the alliance at the state and central levels, alongside the Eknath Shinde-led Shiv Sena faction and the Ajit Pawar-led NCP faction, the seat-sharing arrangement in Mumbai has exposed strains. The Ajit Pawar faction is contesting a substantial number of seats independently in the city, despite being part of the government. The relationship between the BJP and the NCP faction has also been tested by disagreements over campaign leadership and candidate selection, including the BJP’s discomfort with Nawab Malik’s prominent role and the NCP faction’s decision to back him and field multiple members of his family from the Kurla belt.

These contradictions are not confined to Mumbai alone. Across Maharashtra’s civic landscape, the local body elections have revealed sharply divergent alliance behaviours. In Pimpri-Chinchwad and parts of Pune, rival NCP factions have shown signs of tactical accommodation, driven by a shared perception of being marginalised by a dominant ally. In contrast, in Mumbai and Thane, alliance partners are openly pitted against each other, exposing the limits of coalition cohesion. This uneven pattern underlines a central theme of the current round of municipal polls: that local arithmetic, not alliance ideology, is shaping candidate selection and electoral strategy, turning civic bodies into testing grounds for longer-term political survival.

The BJP, for its part, has fielded a large slate of candidates in Mumbai, with the total number of contestants across parties standing at around 1,700, as per the State Election Commission (SEC). Several BJP candidates are recent entrants from rival parties, a strategy that has caused resentment among long-time party workers who feel sidelined. In multiple wards, sitting or former corporators and their relatives have been nominated, while in others, last-minute inductions have altered local equations, creating quiet internal discontent even as the party projects unity at the top.

Campaign rhetoric has also taken a sharper communal and identity-oriented turn. Statements suggesting that the outcome of the election could determine whether Mumbai gets a mayor from a particular community have drawn swift counterclaims. The Thackeray camp has responded by asserting that the city will have a Marathi Manoos as mayor if their alliance succeeds, while the BJP has sought to broaden the frame by emphasising religious identity over linguistic lines, arguing that a Hindu mayor would reflect Mumbai’s demographic realities. The Congress, though comparatively subdued in the public din of the campaign, has attempted to carve out a constitutionalist position, arguing that its vision of leadership is not rooted in religion or community but in citizenship and adherence to constitutional values.

Beyond Mumbai, the BMC election is intertwined with a larger statewide experiment. Civic polls across multiple municipal corporations in Maharashtra are widely viewed as a testing ground for the BJP’s long-articulated ambition of political dominance, often described by critics as a push towards a single-party system. The fact that alliance partners are competing against each other in several cities has reinforced perceptions that traditional norms of alliance discipline have been set aside in pursuit of long-term expansion.

Why the BMC matters so deeply is inseparable from its financial and administrative weight. With a budget larger than that of several Indian states, the corporation controls urban planning, public works, health infrastructure, education, water supply and waste management in a metropolis that drives a significant share of the national economy. Control of the BMC confers not just administrative authority but also immense political visibility and organisational reach, making it a coveted prize for every major party in Maharashtra.

As polling day approaches, the impending BMC election has come to embody far more than a local civic contest. It is a referendum on fractured alliances, on competing visions of identity and development, and on the balance between centralised power and regional assertion. The verdict will decide who governs Mumbai’s municipal machinery, but its political echoes will be felt well beyond the city, shaping narratives about power, opposition and the future trajectory of Maharashtra politics.

*Senior journalist