Study Maps 3,000 Years of Kaziranga’s Ecological Past

Kaziranga’s Past Holds Lessons for Conservation

Lucknow/Guwahati: Scientists have reconstructed the long ecological history of Assam’s Kaziranga National Park (KNP), revealing how climate change, vegetation shifts, invasive species and human activity reshaped the region into the last major stronghold of the one-horned rhinoceros.

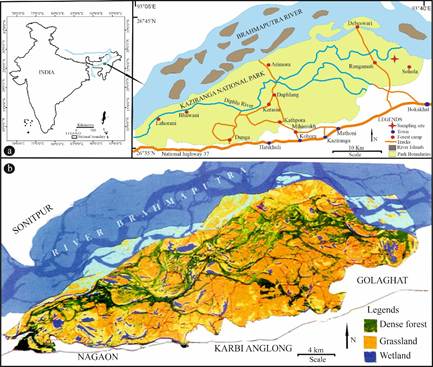

The findings come from a new study by researchers at the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP), an autonomous institute under the Department of Science and Technology (DST), published in the international journal Catena. Using pollen and dung-fungus spores preserved in wetland sediments, the team produced the first long-term palaeoecological and palaeoherbivory record from Kaziranga.

The study places Kaziranga within a larger global crisis. Late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions remain a major scientific concern worldwide, with their causes still debated. Today, nearly 60 per cent of large herbivores are threatened with extinction, and Southeast Asia has the highest number of species at risk. Northeast India, part of the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot, hosts many endangered animals and faces accelerating pressure from urbanisation, deforestation and climate extremes.

Kaziranga National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, has emerged as one of the last refuges of megaherbivores, particularly the Indian one-horned rhinoceros.

To uncover how this happened, scientists extracted a sediment core just over one metre deep from the Sohola swamp inside the park. Each layer of mud acts as a natural archive, preserving microscopic pollen grains from plants and coprophilous fungal spores that grow on animal dung. Samples were collected at five-centimetre intervals and analysed using the standard acetolysis method, with radiocarbon dating establishing the chronology of environmental change over nearly 3,300 years.

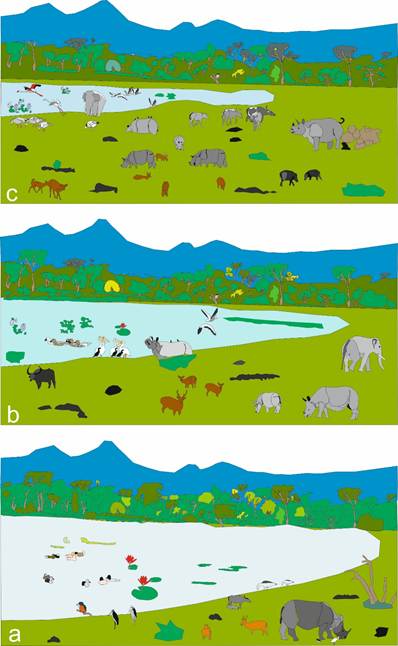

The research identifies three distinct ecological phases in Kaziranga’s history.

Between about 3290 and 1700 years before present, the region supported a dense tropical mixed forest under warm and humid climatic conditions. Tree species such as Bombax, Cinnamomum, Duabanga and Lagerstroemia dominated, while grasslands were limited. Fungal spores linked to animal dung were scarce, indicating comparatively low herbivore activity during this period.

From 1700 to 640 years before present, evergreen forest taxa such as Mesua, Cinnamomum and Litsea declined, while deciduous species, including Bombax, Dillenia and Careya, expanded along with grasslands. The appearance of Mimosa, an invasive plant species considered harmful to native vegetation, marked a major ecological shift. At the same time, increasing concentrations of coprophilous fungal spores such as Sporormiella, Saccobolus and Ascodesmis pointed to a gradual rise in wildlife populations.

During the last phase, from about 640 years ago to the present, forests became less dense and open landscapes expanded. The study records a sharp rise in dung-fungal spores, signalling much higher numbers of large herbivores, including rhinoceroses.

By combining vegetation data with evidence of herbivore presence, researchers concluded that the one-horned rhinoceros and other megafauna once had a far wider distribution across the Indian subcontinent. Fossil and pollen records show that populations declined sharply in northwestern India during the late Holocene due to climatic deterioration during the Little Ice Age and growing human pressures such as habitat loss and hunting.

In contrast, northeastern India remained relatively climatically stable and experienced lower human disturbance. This stability enabled rhinoceroses and other large herbivores to migrate eastward and eventually concentrate in Kaziranga, which became a refuge as suitable habitats elsewhere disappeared.

Although India is among the few countries with technical expertise in palaeoecological reconstruction, the Kaziranga study is the first to document the reciprocal interaction between long-term vegetation change and herbivore populations in this region, using both pollen and fungal spores as biological proxies.

Researchers say the findings provide a historical baseline for understanding how climate and human activity shape biodiversity over centuries. Such long-term ecological knowledge is essential for improving conservation strategies and wildlife management under present and future climate change.

The study underlines that Kaziranga’s present landscape is not timeless but the result of continuous transformation driven by climate shifts, invasive species and animal movement. It also shows that protecting megaherbivores today requires safeguarding the ecological processes that allowed them to survive in the past.

By revealing how ancient climate stability and reduced human pressure turned Kaziranga into the last great home of the one-horned rhinoceros, the research offers crucial insight into why the park remains central to India’s conservation future — and how fragile that legacy may be in a warming world.

– global bihari bureau