America’s New Bridal Party: Netflix and No Wedding

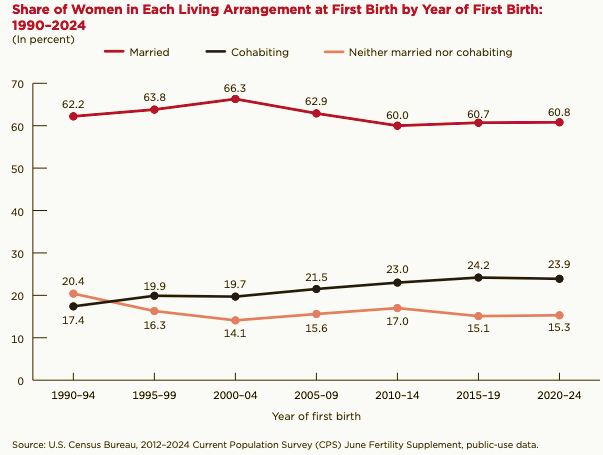

Washington: A larger share of women had their first child while living with an unmarried partner in the early 2020s than in the early 1990s, according to the new Women’s Living Arrangements at First Birth report released by the United States Census Bureau. The finding may not cause a stir in Los Angeles or Atlanta, but in many corners of the world—from Bihar’s deeply conservative districts to the Gulf’s traditional expatriate enclaves and East Africa’s church-governed towns—the idea that nearly one in four American first-time mothers was cohabiting rather than married at childbirth is nothing short of arresting. Yet behind the headline number lies a long social evolution—slow, steady, and profoundly human.

When researchers asked thousands of American women to recall the moment they became mothers for the first time, their responses did more than fill a statistical spreadsheet. They revealed a story of shifting expectations, of families built outside older templates, of communities adapting to new realities, and of women navigating motherhood in ways their own mothers could scarcely imagine three decades ago.

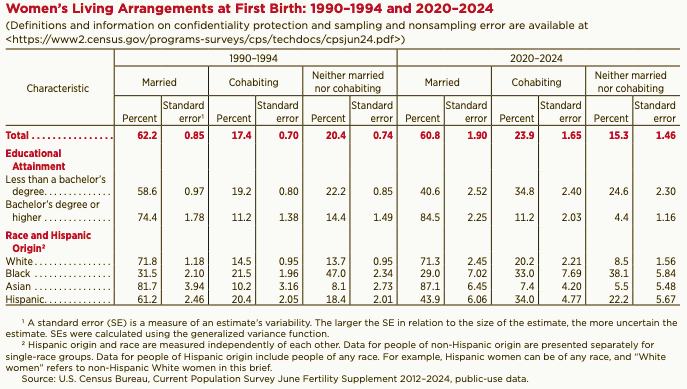

In the early 1990s, the United States still lived in a world where marriage formed the default gateway to motherhood. Only 17.4 per cent of first-time mothers lived with an unmarried partner at the birth of their child. Today, that share has climbed to 23.9 per cent—a rise built not from sudden cultural shocks but from countless quiet decisions: a couple moving in together to save rent, two young professionals postponing marriage for career goals, or a woman who finds emotional security with a partner but sees no urgency in legal vows. These choices, multiplied across millions, have slowly reshaped the landscape of American family life.

But if cohabitation has expanded, marriage itself has not vanished. The report notes that the overall share of married first-time mothers has barely changed—62.2 per cent in the early 1990s and 60.8 per cent in the early 2020s. The stability is deceptive, because it conceals one of the starkest social divides in contemporary America: the gap between women with a bachelor’s degree and those without one.

Among highly educated women, the trend is not toward cohabitation but toward strengthening the marital model. In 1990–1994, about 74.4 per cent of mothers with a bachelor’s degree or more were married at their first birth. By 2020–2024, that figure had jumped to 84.5 per cent. Their share of unpartnered first births plummeted to just 4.4 per cent. Education, long seen as a gateway to career and income, is now just as clearly a gateway to the likelihood of raising children within marriage. Sociologists have been describing this as the “marriage privilege”—an institution increasingly retained by the economically secure.

The story for women without a college degree is far different, shaped by fluctuating jobs, low wages, uncertain housing, and the prohibitive costs of weddings, childcare, and healthcare. Their marital first births fell from 58.6 per cent in the early 1990s to 40.6 per cent today, while cohabitation climbed from 19.2 per cent to 34.8 per cent. A young waitress in Georgia, recalling her first birth in the 2000s, told Census interviewers that she and her partner “felt like a family, even if we never signed a paper.” Her sentiment reflects a generation for whom partnership often precedes, substitutes for, or outlasts marriage.

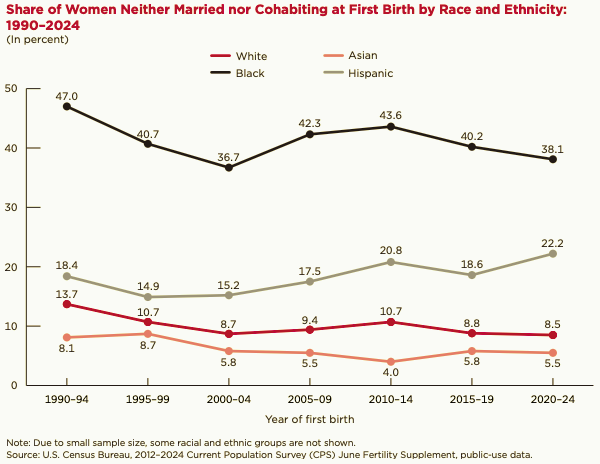

Race and ethnicity shape the story just as sharply. In the early 1990s, Asian mothers were the most likely to be married at first birth, at 81.7 per cent—a figure that climbed to 87.1 per cent in the early 2020s, making them the most consistent retainers of traditional family structures. White women, too, stayed stable at around 71 per cent. The steepest descent occurred among Hispanic women, whose marital first births dropped from 61.2 per cent to 43.9 per cent over thirty years. Black women, meanwhile, remained at roughly 29 per cent across both periods—a reflection of structural inequality, social histories, and economic pressures that continue to shape family life across generations.

The data on unpartnered first births paints one of the more complex social portraits. In the early 1990s, nearly half of Black first-time mothers—47 per cent—had their child outside marriage and without a partner present. That figure has not changed significantly even after three decades. Among Hispanic women, the shift has also been marginal, from 18.4 per cent to 22.2 per cent. White women witnessed a notable decline from 13.7 per cent to 8.5 per cent, while Asian women remain the least likely to be unpartnered at childbirth.

Zooming out to a global context, these numbers invite comparison. In much of South Asia, childbirth outside marriage remains rare, stigmatised, or even dangerous. Many African and Middle Eastern societies tie childbirth to legal or religious marriage contracts. In traditional East Asian societies—Japan, Korea, and China—cohabiting births are still highly uncommon, despite declining marriage rates. In contrast, Scandinavian countries witness some of the world’s highest rates of cohabiting births, driven by universal childcare, gender equality, and social norms that treat cohabiting parents no differently from married ones. The United States stands somewhere in the middle. Its cohabitation rates are rising, but not at Scandinavian levels. Its marriage rates are declining, but not as sharply as those in parts of Europe. Its norms are liberalising, but unevenly, and deeply interlinked with race, class, and education.

For families around the world observing America’s demographic evolution, the report offers insight into how economic structures influence family systems. A young Indian couple living in Bengaluru, for instance, might remark on how unimaginable it is in their context to start a family without parental blessings and ceremonial rituals. A Filipino migrant worker in Dubai may note that cultural expectations in her community would not permit childbirth outside marriage, regardless of changing global attitudes. Yet in America, an entire generation has quietly grown up treating partnership—married or unmarried—as a private equation rather than a societal contract.

One of the strengths of the Census Bureau report is its ability to blend sweeping demographic changes with unseen personal narratives. Each figure hints at a story. A woman who was 20 in 1992 may recall feeling that marriage was simply what one did before having a child. A woman who became a mother in 2022 may describe a different world—one in which she and her partner lived together for years, shared expenses, planned carefully for a baby, and saw no compelling reason to marry. Another mother may recall raising her first child alone because her partner worked seasonal jobs, or moved across states, or because the relationship did not survive economic strain. These stories, though unspoken in the report, shape every statistical curve.

The long arc of data from 1990 to 2024 shows a society adapting gradually rather than drastically. Cohabitation is rising, but marriage persists. Economic divides widen, shaping who marries and who does not. Racial patterns endure, echoing historical inequalities. And through it all, motherhood remains an anchor, a transformative experience recalled vividly by women across ages, races, and regions—even as the structures surrounding it evolve.

For policy thinkers, the report raises crucial questions. Do children have equal access to resources across these diverse family forms? Does cohabitation provide stable support, or does it leave mothers more vulnerable? Should governments expand childcare, housing, and income-support programmes to reduce disparities? For global readers, the American data is a window into how social norms shift when law, culture, economics, and individual agency intersect over decades.

What the data ultimately reveals is not a collapse of tradition but a diversification of paths into motherhood. In the world’s most culturally diverse and economically unequal high-income nation, women are crafting families that reflect their realities, not just societal scripts. The arrival of a first child—whether into a married home, a cohabiting one, or a single-parent household—remains one of the most profound human transitions. The Census numbers capture the frameworks; the lived stories fill in the rest.

– global bihai bureau