New Delhi: Her hands tremble from years of fists, dowry demands, or being discarded like trash, her spirit battered but unbowed. A young boy nearby, orphaned by loss, grips a frayed toy, his eyes searching for safety. On a sprawling campus in Najafgarh, Delhi, Sweet Home and Maika Sweet Home stand as a lifeline for an ever-shifting community of women and children, their numbers fluctuating as new faces arrive and others step toward independence.

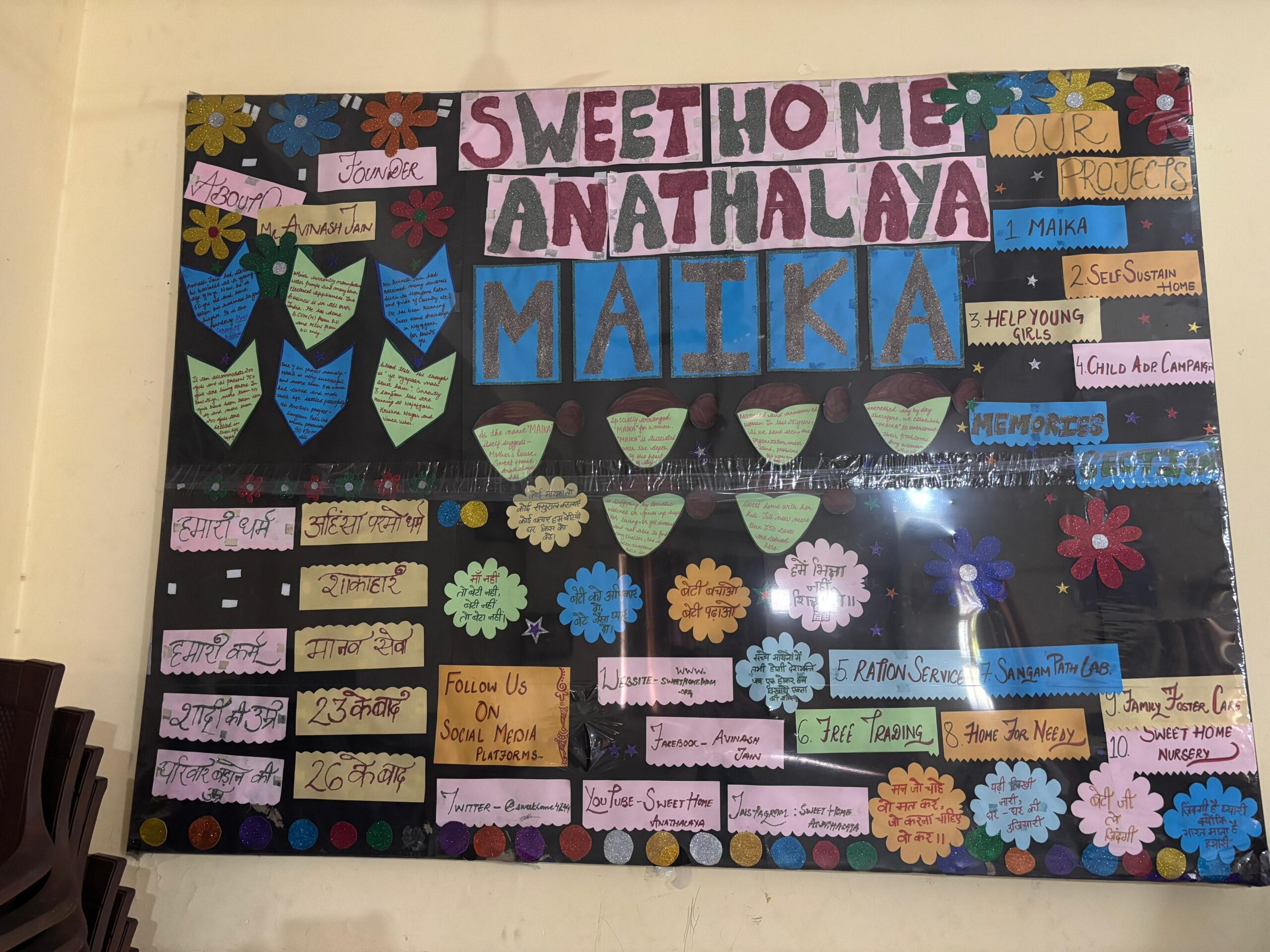

Sweet Home, founded in 1996 by Avinash Jain—a tenacious entrepreneur who grew Arise India from a small hardware store into a company which sponsored the 2014 Asia Cup cricket in 2014—is an orphanage for boys and girls, offering a childhood stolen by tragedy. Maika, launched in 2021 on the same grounds, is a “mother’s home” for women over 18 escaping domestic violence and their children – girls can stay, but boys should not be more than seven years old.

Unlike orphanages governed under the Juvenile Justice Act or government-run old age homes, India currently lacks a dedicated policy framework or licensing category for shelter homes like Maika, which support women fleeing domestic violence along with their young children. The unique needs of women and their children—who must stay together—are often unmet due to the absence of structured support systems. While courts often cannot provide timely solutions, in most cases, counselling and temporary separation resolve issues without litigation.

We’ve resolved over 7,500 such cases without involving courts,” Jain said. Calling for a National Policy on Shelter Homes for Domestic Violence Survivors, he urged the central government to formally recognise and categorise such shelters under the policy. He stressed, “There should be clear WCD-level (Women and Child Department) licensing provisions so NGOs can legally operate and expand such shelters across India”.

This isn’t Jain’s lone fight; it’s a raw, collective stand by staff, volunteers, and donors who pour their grit into this refuge. “Whenever there is a deficit in donations, the founding family personally steps in to ensure no resident’s well-being or the shelter’s functioning is compromised,” Jain says, his words binding a community that defies despair.

What makes Maika stand out is its rejection of barriers that lock survivors out. Unlike most shelters in India, it demands no First Information Report (FIR) to prove abuse—just a birth certificate for children if available—and sets no deadline for leaving. “Here, we are not just surviving, we are learning to fly,” says a Maika resident, her voice steady with newfound strength, her name withheld for safety. This open-door policy, rare in a system choked by bureaucracy, lets women heal at their own pace. Maika’s holistic approach goes further: it’s a crucible for empowerment, blending education, vocational training, language courses, and emotional support to shatter cycles of poverty and violence. From computer literacy to jobs in multinational firms, Maika equips survivors to rewrite their futures, a model that, paired with Sweet Home’s nurturing of orphaned children, offers philanthropists a blueprint for transformative change.

The campus crackles with life, though pain lingers like a shadow. Sweet Home’s kids tear through open spaces, their shouts mixing with the clatter of toy cars and basketballs. Rooms in both homes burst with crayon drawings and paper stars, pinned up by children who’ve never had a wall to claim. A girl, barely ten, traces a birthday chart, her first celebration marked by crafts from peers who know abandonment’s sting. “I’d never had a birthday before,” she says, her voice soft but eyes fierce with hope. “Now I have sisters who care.”

In Maika, women share rooms with their kids, large beds a stark contrast to the bare floors or worse they’ve endured. Special rooms for pregnant women, the elderly, and small children ensure tailored care, while attached washrooms restore dignity. A small mandir in the great hall hums with prayers, where residents from both homes gather, their voices weaving a fragile but fierce family during festivals like Janmashtmi, with children playing as Bal Gopal and Gopis, and, Raksha Bandhan, with vibrant threads tying siblings in spirit.

The women in Maika carry wounds that don’t always show—bruises faded, fears that gnaw like ghosts. Many fled husbands whose rage spilt beyond fists, leaving threats scrawled on walls or bottles shattered in their wake. “Out there, I was nothing. Here, I’m learning to stand,” says one woman, her voice cracking but defiant, her name withheld for safety. Another adds, “They broke my body, but this place is mending my soul.” Maika’s no-FIR policy means a woman doesn’t need to navigate police stations or courts; she just needs to arrive.

The women in Maika carry wounds that don’t always show—bruises faded, fears that gnaw like ghosts. Many fled husbands whose rage spilt beyond fists, leaving threats scrawled on walls or bottles shattered in their wake. “Out there, I was nothing. Here, I’m learning to stand,” says one woman, her voice cracking but defiant, her name withheld for safety. Another adds, “They broke my body, but this place is mending my soul.” Maika’s no-FIR policy means a woman doesn’t need to navigate police stations or courts; she just needs to arrive.

Sweet Home mirrors this, taking in orphans—often through police or social workers—with minimal paperwork, prioritising safety over red tape. “This is my first real home,” says a teenage boy from Sweet Home, his voice thick with emotion. “They don’t just feed us; they believe in us.”

Both homes ensure medical care through partnerships with the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) and the Safdarjung Hospital, offering dental checkups, eye camps, and hygiene sessions to counter health risks.

Personal files brim with victories—math scores, art awards, competition certificates—each a rebellion against a past that tried to erase them. Transformation is the pulse here. Nine computers hum in a lab where women and older kids learn digital skills to crack a world that once shut them out.

A library overflows with books, from algebra to fairy tales, feeding minds starved for knowledge.

Maika’s vocational courses—stitching, designing, beauty work—are lifelines; some women now hold jobs in multinational companies, a leap unimaginable in their former lives. One woman, who arrived shattered, now runs Maika’s Instagram, sharing survival stories with 261,000 followers as of August 2, 2025, her journey a flare of hope. “I was invisible,” she says. “Now my story helps others stand tall.” Sweet Home’s older children join these programmes, learning alongside Maika’s residents, their paths converging toward self-reliance.

Sundays are a release valve—kids swarm trampolines, race cycles, or lose themselves in TV, laughter echoing across the campus. Those over 15 scrub pots or sweep floors, not as chores but as stakes in a home they’re building, fostering discipline through shared responsibility. “We’re a family here,” says a Sweet Home girl, clutching a trophy from a recent art contest. “We lift each other up.”

The struggle is brutal. Funding is a constant fight—donations and the Jain family’s resources keep the lights on, as Jain notes. Mental health support strains under trauma’s weight; counsellors, though dedicated, can’t always reach the deepest scars. Society’s stigma clings, making jobs or reintegration a battle against judgment. Maika attempts to mediate family disputes, but only 5–10% resolve—safety always trumps reconciliation. Women over 18 get mobile phones, a vital link to the outside world, but no one’s pushed into adoption or marriage; the focus is rising. “If there is a good match, then only we consider marriage of the girls,” Jain says. Trophies from sports and art contests line the walls, each a jab at a world that wrote them off.

Maika’s novelty lies in its refusal to let survivors be defined by their pasts. Its open-door policy, lack of time limits, and comprehensive empowerment programmes—spanning education, vocational training, English courses, and emotional care—create a model that doesn’t just shelter but transforms. Sweet Home complements this, offering orphaned boys and girls a parallel path to dignity through education and moral grounding. Together, they form a campus that’s more than a refuge; it’s a proving ground for resilience, sustained by a collective of staff, volunteers, and donors who refuse to let despair win. “They said we’d never be anything,” a young woman says, her smile sharp as a blade. “Look at us now.”

For philanthropists, this campus is a call to action and a blueprint. Maika’s approach—minimal entry barriers, long-term support, and a focus on self-reliance—offers a scalable model for addressing domestic violence and poverty. Sweet Home’s care for orphans, from providing basics like food and shelter to fostering ambition through education, shows how to break cycles of deprivation.

The campus thrives on practical systems: a library stocked with academic and storybooks, a computer lab with nine systems, vocational workshops teaching stitching, design, and beauty skills, and partnerships with AIIMS, Safdarjung Hospital, and local schools for healthcare and education.

The Maika Sweet Home leans on community—residents over 15 contribute to daily tasks like cooking and cleaning, donors provide funds or goods like clothes and trinkets, and volunteers offer time, from teaching to organising events. Jain’s Arise India, built from a 1988 hardware store to a manufacturer of electrical goods, underscores the power of persistent vision, a lesson for anyone aiming to launch a similar venture. The Sangam Path lab, run by Sweet Home with the motto “ye vyapaar nahi sewa hai” (this is not business, but service), offers medical tests at up to 90% lower rates, showing how social enterprises can amplify impact.

This isn’t a tidy success story—it’s a fight, messy and real, against odds that don’t quit. The campus demands we look: to donate clothes, books, or funds; to volunteer time or expertise; to learn from its model and build new havens for those society discards. Maika and Sweet Home are a collective middle finger to despair, fueled by those who give everything to see survivors rise. “Look at us now,” the young woman repeats, her words a challenge to anyone with the means to act. Today, this is where pain meets power, where philanthropists can find not just inspiration but a practical path to change lives. Maika is advocating for the establishment of at least 100–150 such shelter homes district-wise across India to address the growing matrimonial crisis through holistic, non-legal solutions.