By Deepak Parvatiyar*

By Deepak Parvatiyar*

Latin Journalism: Watchdog Ideals vs. Real Risks

In the intricate mosaic of global media landscapes, Latin America emerges as a region where the pursuit of factual reporting collides persistently with danger, economic fragility, and structural pressures. For decades, it has been among the most demanding regions in the world in which to practice journalism, shaped by recurring political instability, organised crime, weak institutions and uneven democratic consolidation. From the era of military dictatorships to contemporary forms of authoritarian rule, journalists across the region have learned to operate in environments where professional independence is rarely guaranteed and often contested.

What distinguishes the present moment, the editors of a major new study argue, is not simply the persistence of pressure, but how journalists have recalibrated their professional roles, ethical boundaries and daily routines in response to it.

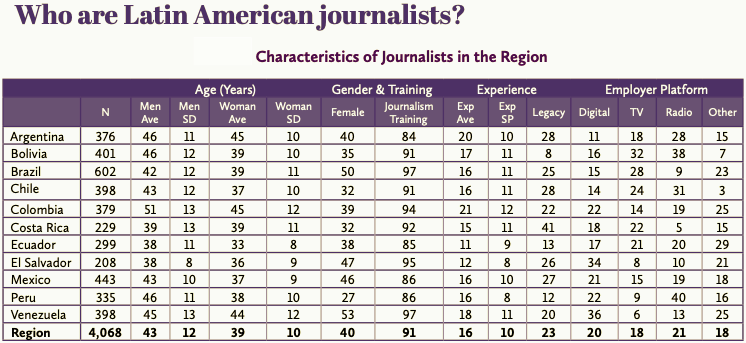

These recalibrations form the empirical core of The Worlds of Journalism: Safety, Professional Autonomy, and Resilience in Latin America, a regional volume of the global Worlds of Journalism Study, released today. Based on surveys of more than 4,000 journalists across eleven countries and data collected between 2021 and 2024, the book offers a detailed, comparative account of how journalists understand their work under conditions of risk, constraint and uncertainty. Rather than cataloguing attacks or tracing legal frameworks, the study focuses on how journalists themselves define professionalism, autonomy and resilience within their national contexts. It offers a comparative, empirically grounded portrait that moves beyond episodic crises to reveal journalism as a profession shaped by structural adaptation as much as resistance.

These recalibrations form the empirical core of The Worlds of Journalism: Safety, Professional Autonomy, and Resilience in Latin America, a regional volume of the global Worlds of Journalism Study, released today. Based on surveys of more than 4,000 journalists across eleven countries and data collected between 2021 and 2024, the book offers a detailed, comparative account of how journalists understand their work under conditions of risk, constraint and uncertainty. Rather than cataloguing attacks or tracing legal frameworks, the study focuses on how journalists themselves define professionalism, autonomy and resilience within their national contexts. It offers a comparative, empirically grounded portrait that moves beyond episodic crises to reveal journalism as a profession shaped by structural adaptation as much as resistance.

A central contribution of the volume lies in its examination of role conceptions—how journalists see their function in society. Across most countries surveyed, journalists continued to express strong commitment to watchdog and investigative roles, particularly the monitoring of political power and exposure of wrongdoing. However, the study reveals important national variations. In countries marked by high levels of repression or insecurity, journalists were less likely to endorse interventionist or adversarial roles and more likely to emphasise cautious information provision, conflict avoidance and personal safety. These shifts did not reflect a rejection of public-interest journalism, the editors argue, but a strategic narrowing of professional ambition under pressure.

Mexico illustrates this tension with particular clarity. Journalists surveyed reported frequent exposure to threats and intimidation related to their reporting, especially among those covering crime, corruption and local politics. The book shows that while Mexican journalists continue to value watchdog journalism in principle, they are significantly more likely than peers in some other countries to engage in selective coverage, avoidance of specific actors and careful framing of sensitive topics. These practices are concentrated among journalists working in local and regional outlets, where proximity to power and limited institutional support heighten vulnerability. In this context, the study treats self-restraint not as ethical erosion but as an embedded professional adaptation.

In Central America, the book documents how political systems shape journalistic roles in distinct ways. In Nicaragua, journalists reported severely constrained autonomy, with high levels of perceived surveillance, legal pressure and editorial interference. Respondents described a professional environment in which independent journalism is increasingly practised from exile or through fragmented networks rather than stable newsrooms. In Honduras and El Salvador, journalists reported a combination of political pressure, economic precarity and security concerns, with respondents frequently identifying legal risk and institutional weakness as factors shaping editorial decisions. Across these countries, the study highlights how role conceptions shift toward risk minimisation without disappearing entirely.

Venezuela presents a different configuration of constraints. Journalists surveyed described overlapping pressures—legal, political and economic—that limit editorial independence and undermine newsroom stability. The study documents how journalists increasingly rely on small, digital-native outlets as spaces for reporting, while simultaneously reporting high levels of uncertainty regarding income, sustainability and personal risk. Here, resilience appears less as institutional strength than as individual and collective improvisation within a fragmented media environment.

South American cases add texture: Brazil reports relatively high perceived autonomy in story selection amid polarisation, online harassment, and hostility—pressures reshaping credibility assessment, audience engagement, and exposure management, particularly for women. Argentina foregrounds economic insecurity—temporary contracts, multiple jobholding, declining resources—as primary barriers to investigative depth. Colombia, shaped by decades of conflict and uneven state presence, sees rural journalists facing heightened threats on local governance, corruption, and environmental beats. Yet, the book shows that Colombian journalists maintain strong support for investigative and public-interest roles, while simultaneously integrating risk assessment into routine editorial practice. This coexistence of professional commitment and caution exemplifies what the editors describe as ‘negotiated autonomy’.

Consistent patterns span the region: widespread verbal abuse, intimidation, and harassment (increasingly digital); disproportionate online harassment and discrimination for women; greater instability and limited support for freelancers and younger practitioners. These conditions, the editors argue, are not peripheral but central to understanding how journalism is practised.

One of the book’s most important analytical contributions lies in how it reconceptualises resilience. Rather than framing resilience as individual courage, psychological endurance or moral steadfastness, the editors treat it as a set of observable professional practices that emerge under constraint. Across national contexts, journalists described adapting their work in concrete ways: collaborating across outlets to dilute individual exposure, narrowing beats to avoid predictable risks, relying on trusted sources rather than open reporting, shifting from investigative depth to explanatory or contextual journalism, and experimenting with digital formats that offer greater flexibility but fewer guarantees. These practices, the study suggests, are neither temporary nor exceptional. They represent a durable mode of journalistic practice shaped by prolonged exposure to risk.

Crucially, the book shows that these adaptations do not occur uniformly. Media systems, labour markets and political environments condition journalists’ responses to pressure. In countries where repression is overt and institutional checks are weak, resilience takes the form of mobility, exile-based reporting and fragmented newsroom structures. Where political pressure is less direct but polarisation is intense, journalists emphasise credibility management, audience engagement and defensive professionalism. In contexts marked primarily by economic instability, resilience is expressed through multiple job holding, freelance networks, and the redefinition of career trajectories. By tracing these patterns comparatively, the book avoids reducing Latin American journalism to a single narrative of crisis.

The volume also complicates common assumptions about professional autonomy. Survey respondents across several countries reported a sense of autonomy in selecting stories and framing coverage, even while acknowledging external pressure, self-restraint and interference —coexistence explained by active interpretation and negotiation of boundaries. Rather than dismissing these responses as contradictory, the editors argue that autonomy must be understood relationally. Journalists operate within boundaries, but those boundaries are actively interpreted, negotiated and sometimes reshaped. This challenges “free vs. unfree” binaries, portraying systems as defined by shifting red lines, informal pressures, and anticipatory practice—journalism conducted in expectation of consequences. Autonomy, in this sense, is not the absence of constraint but the capacity to manoeuvre within it. This insight helps explain why journalists can simultaneously express commitment to watchdog ideals and acceptance of limits on what can safely be reported.

Another important contribution of the book lies in its attention to inequality within the profession: risk distributes unevenly—women facing elevated harassment shaping confidence/trajectories; younger/freelance journalists encountering greater instability/vulnerability. These patterns suggest that precarity is not only an economic condition but a factor that reshapes professional voice and visibility within newsrooms.

By foregrounding journalists’ own assessments of their working conditions, the book also challenges simplified distinctions between “free” and “unfree” media systems. Across the region, journalists described environments that are neither fully open nor entirely closed, but characterised by shifting red lines, informal constraints and episodic enforcement. The result is a form of journalism practised in anticipation of consequences rather than in response to explicit rules. This anticipatory dimension, the editors argue, is central to understanding how power operates in contemporary media systems.

The research was conducted as part of the global Worlds of Journalism Study, an international collaboration examining journalism cultures and working conditions in more than seventy countries. The Latin American volume was produced in close collaboration with the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas, which supported research coordination and regional dissemination. The Knight Center, based at the University of Texas at Austin, has played a sustained role in advancing research, training and dialogue on journalism in the region, particularly in contexts marked by democratic stress and rapid digital transformation.

The foreword by Knight Center director Rosental Calmon Alves adds historical resonance, invoking Gabriel García Márquez’s 1996 affirmation of journalism as the world’s finest profession amid persistent adversity, while highlighting the Center’s role in fostering independent associations, massive online education (over 350,000 participants), symposia, and the LatAm Journalism Review—efforts now deepened by this study’s insights into resilient, value-driven journalists facing precarity (nearly half without full-time contracts), gender disparities (women ~40%, younger, more safety-concerned), mistreatment (>50% hateful speech, ~33% surveillance/bullying), mental strain (>70% emotional concerns), self-censorship (~50%), peer reliance (~70%), and strong democratic commitments despite autonomy gaps.

Edited by Summer Harlow, Sallie Hughes and Celeste González de Bustamante—scholars with long-standing expertise in journalism, media systems and Latin America—the book is careful not to frame its findings as a story of professional decline. Instead, it presents journalism in Latin America as a field undergoing continuous recalibration. Professional norms persist, but they are reinterpreted through daily encounters with risk, insecurity and constraint. Ideals are not abandoned; they are adjusted, narrowed, defended and sometimes deferred.

Taken as a whole, The Worlds of Journalism: Safety, Professional Autonomy, and Resilience in Latin America offers a rare, empirically grounded account of how journalism functions when pressure is not exceptional but structural. Its value lies not only in documenting hardship, but in showing how journalists actively make sense of it—how they redefine what it means to report, to be autonomous and to serve the public under conditions that limit certainty and protection. In doing so, the book moves the discussion beyond episodic crises and isolated threats, offering a deeper understanding of journalism as a profession shaped as much by adaptation as by resistance.

*Senior journalist