Guns, Grants, and Geopolitics: America’s Expensive Peace

The wars in Gaza and Ukraine highlight the pivotal role of the United States’ military assistance, revealing how arms transfers and security grants shape Washington’s global influence. For Israel, a long-term ally, aid is predictable and structured; for Ukraine, a democracy under siege, it’s rapid and reactive. These cases reflect the dual nature of American power—rooted in strategic leverage and economic gain through its defence industrial base.

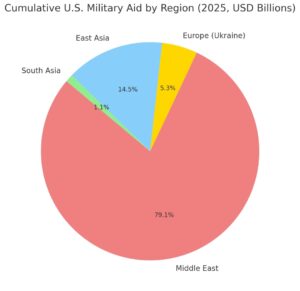

The United States runs a large, complex foreign-security assistance system that blends strategic calculation with industrial policy. The high-profile examples — the long-term security compact with Israel, wartime assistance to Ukraine, episodic aid to Pakistan, and steady military grants to partners such as Egypt and Jordan — reveal how U.S. aid functions simultaneously as a foreign policy tool, economic stimulus for the U.S. defence industrial base, and a predictable but politically contentious element of global security architecture.

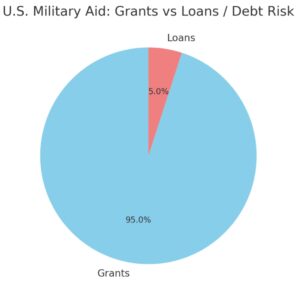

A recurring question is whether nations like war-ravaged Ukraine or economically fragile Pakistan repay this aid. In most cases, they do not, as the bulk of U.S. military assistance is structured as grants rather than loans. Pakistan receives conditional grants or Foreign Military Sales credits rather than loans requiring direct repayment. The United States, in theory, protects its interests through safeguards, including end-use monitoring to ensure weapons are used for defence purposes only, policy conditions linking aid to counterterrorism compliance or human rights standards, and industrial leverage that ensures most funds are spent in the U.S., returning money to domestic manufacturers. Because of these measures, military aid is not a debt trap; recipients face operational and political dependence, but they are not forced into financial obligations that could destabilise their economies.

In the case of Ukraine, while some of the macro-financial aid is structured as loans, with loan guarantees from the U.S. Treasury, Ukraine’s emergency packages since 2022 — totalling over USD 66.5 billion — too, are largely grants and equipment drawdowns, not debt obligations.

The mechanics matter. As most Foreign Military Financing (FMF) is structured as grants, not loans, this means they don’t need to be repaid, but a large portion must be used to purchase U.S.-manufactured weapons, parts and services. The money is deposited into an account at the U.S. Treasury, and allies can use it (with U.S. oversight) to buy American-made weapons and defence systems. That design channels aid dollars back into American factories, sustaining defence-sector employment and long supply chains even as it arms recipient forces.

From a domestic political economy standpoint, this is often sold as a “win-win”: allies such as Israel receive advanced capabilities, and U.S. firms and workers benefit from foreign sales that are effectively subsidised by taxpayer appropriations. The State Department and Congressional analyses make clear that FMF and missile-defence cooperative funds are routed with those procurement conditions in mind.

Israel’s reliance on U.S. grants exemplifies how structured aid shapes long-term military planning while anchoring the U.S. defence industrial base. Historically, Israel received some loans (1950s–1980s), which it repaid, but since the 1990s, aid has shifted to grants. This system fosters strategic reciprocity—the recipient, such as repaying in non-monetary ways by providing the U.S. with intelligence, military technology, and a testing ground for American systems; sharing counterterrorism data and cyber defence innovations, which U.S. agencies find valuable. Thus, while Israel does not repay in cash, it’s treated as a strategic exchange, not a financial transaction.

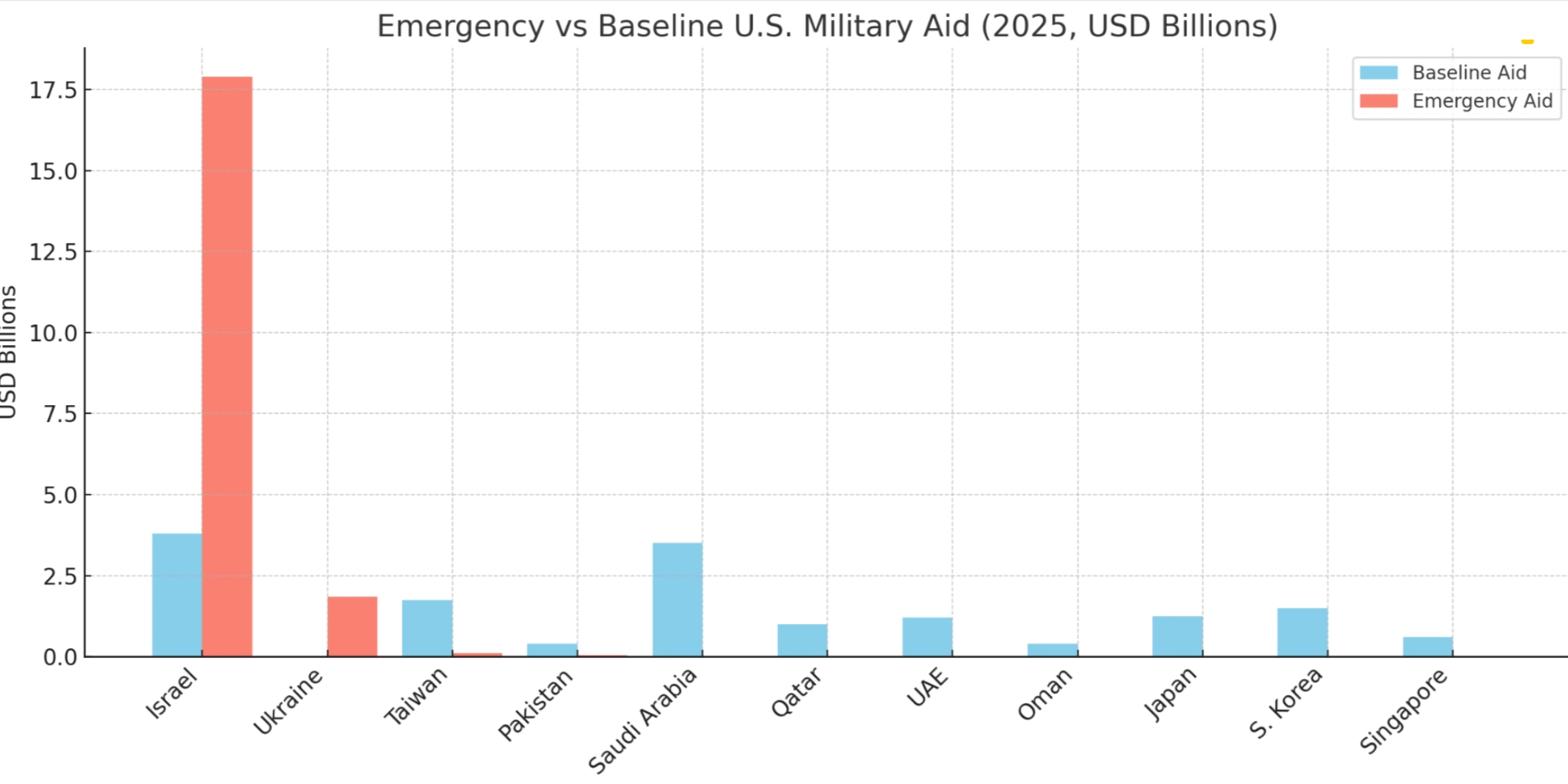

Israel receives USD 3.8 billion annually through 2028 (USD 3.3 billion FMF, USD 500 million missile defence), fully spent on U.S. equipment like F-35 jets, Iron Dome, and Arrow-3 systems, ensuring its qualitative military edge. Emergency aid for Gaza in 2024–2025 added USD 17.9 billion via supplemental packages and stockpile drawdowns. This predictable funding shapes Israel’s long-term planning, while joint R&D, intelligence sharing, and counterterrorism data deliver U.S. dividends, reinforcing a durable security partnership.

Ukraine presents a contrasting, high-velocity model of U.S. military aid. It received over USD 66.5 billion since Russia’s 2022 invasion, mostly grants and equipment drawdowns, with the recent 2025 packages of USD 1.85 billion (USD 1 billion drawdown, USD 850 million via Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative). This aid sustains Ukraine’s resistance but depletes U.S. inventories, spurring domestic production. The scale and pace of recent emergency assistance — most notably to Ukraine since 2022 — underscore how quickly security assistance can expand beyond ordinary baselines. Since the full-scale Russian invasion, Washington and allied capitals mobilised tens of billions in weapons, training, and economic support; U.S. wartime support for Ukraine alone runs into the tens of billions of dollars and has included direct grants, loan guarantees, and drawdowns of U.S. stockpiles. Those flows have been decisive in sustaining Ukraine’s resistance. Still, they are also expensive and politically contested at home, where they compete with domestic budget priorities and contribute to higher Congressional scrutiny of future authorisations.

Although the aid yields domestic benefits—jobs, subcontractor growth, and manufacturing resilience—it risks supply-chain vulnerabilities, per Government Accountability Office reports. Emergency aid to Ukraine and Israel in 2024–2025 underscores the fiscal pressures: while allies gain advanced capabilities, U.S. stockpiles are drawn down, Congress must approve supplemental packages, and domestic budgets face trade-offs. The economic ripple includes subcontractors, logistics, and services, and the political payoff is that Congressional delegations frequently see tangible jobs in their districts tied to foreign military sales. Over decades, this has produced dependency patterns: some states channel local defence budgets into personnel and maintenance while relying on U.S. grants for high-end platforms, shaping force structures in ways that reflect donor priorities as much as local threat assessments. Some policy scholars point out that foreign assistance should be read as both security cooperation and de facto industrial policy.

In the case of both Israel and Ukraine, the United States converts foreign security needs into domestic economic gain while also exerting strategic influence abroad. Both cases also convert foreign needs into U.S. economic gains by boosting contractor sales and manufacturing capacity, and fostering dependency on American technology.

Beyond individual countries, the United States maintains defence commitments across the Islamic Gulf and Indo-Pacific regions. Other recipients illustrate varied patterns. Taiwan accesses arms like F-16Vs and Harpoon missiles through Foreign Military Sales, bolstering deterrence against China without formal alliances. Pakistan’s aid, historically large but now conditional and episodic, acts as a lever of influence, prompting diversification to other partners. Gulf states (Saudi Arabia, Qatar, United Arab Emirates and Oman) rely on U.S. systems, joint exercises, and maritime-security cooperation to protect borders and critical infrastructure. Egypt and Jordan receive a mix of military and economic aid, but these are grants, not loans, tied to the 1978–79 Camp David Accords to maintain peace with Israel. Economically advanced partners like Singapore, Japan, and South Korea maintain robust militaries while leveraging U.S. extended deterrence, co-development programmes, and forward-deployed bases.

These arrangements generate significant procurement opportunities for U.S. contractors, maintain interoperability, and reinforce security umbrellas, yet they also create long-term dependence on American technology and logistics.

U.S. military assistance averaged USD 6–7 billion annually over the past decade, with 2024 arms exports exceeding USD 318.7 billion, driven by Ukraine and regional tensions.

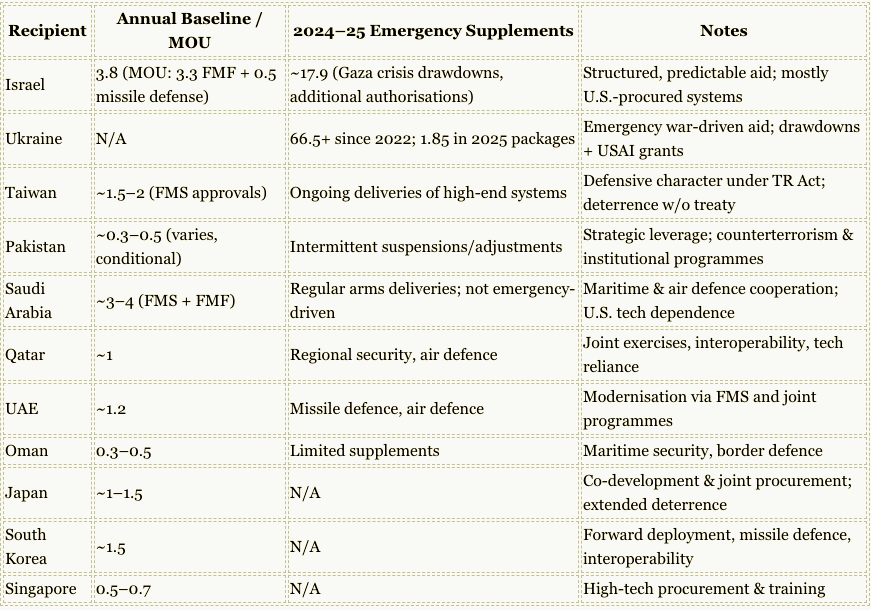

The table below summarises the estimated 2025 aid by major recipient (USD billions):

There are clear domestic economic effects. Government appropriations for foreign military grants boost sales for major U.S. defence contractors and preserve highly skilled manufacturing capacity that might otherwise atrophy in peacetime.

Strategically, the U.S. sees its aid as a deterrence to aggression; it stabilises alliances and extends American influence. Economically, it sustains the American defence industrial base, preserves high-skilled jobs, and supports global competitiveness.

Yet the moral and political calculus is complex: massive aid prolongs conflicts, reinforces regional arms races, and deepens strategic fault lines. While these grants appear indispensable for the immediate security of key allies, they risk deepening divisions with China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, who perceive U.S. support as a challenge rather than protection. This encourages military modernisation, assertive postures, and complicates diplomacy. Humanitarian costs are unavoidable: prolonged conflicts, civilian casualties, and infrastructure devastation often accompany high-volume aid. The Gaza massacre illustrates this, and so does the Russia-Ukraine war.

For peace, military assistance must align with diplomacy and accountability to resolve, not entrench, conflicts—otherwise, it risks militarising and polarising the world, and is precarious.

*Senior journalist