Bamiyan Historic Site

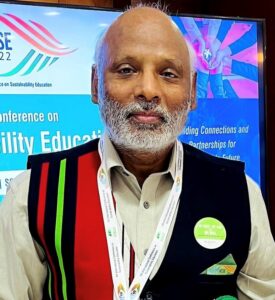

– By Dr Ram Boojh*

– By Dr Ram Boojh*

Why the World Couldn’t Save the Bamiyan Buddhas?

Culture and heritage are of immense value to humanity, yet they face continuing threats from various factors, including armed conflicts, terrorism, vandalism, and illicit trafficking, along with climate change impacts like pollution, erosion, and extreme weather events.

The impetus to safeguard the cultural heritage came from the incidence of the threat to the Abu Simbel temple in Egypt from the construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1959, when an international safeguarding campaign was launched by UNESCO. The campaign resulted in the 1972 Convention concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage, also referred to as the World Heritage Convention, which recognises the world’s most iconic cultural and natural properties as World Heritage. As per the Convention, the signatory countries known as State Parties of the Convention are duty-bound to identify, protect, and preserve the world heritage in their jurisdiction. As of now, there are 196 Parties, 1248 World Heritage Sites, which include 972 Cultural, 235 Natural and 41 Mixed properties in 170 countries. India has a total of 44 sites as of November 2025, which include Ajanta Caves, the Taj Mahal, and the Sun Temple at Konark and this year’s addition of the Maratha Military landscape.

Many Heritage Sites Remain Vulnerable

The World Heritage Convention has been able to recognise and put appropriate safeguards for the designated World Heritage sites, yet many of these sites continue to face serious risks. UNESCO places such sites under the ‘In Danger’ list, signifying that the outstanding universal values (OUVs) of these sites are under severe threat. The In Danger listing is meant to encourage corrective action by the respective country to restore the OUV of the site. Currently, several sites in Ukraine are on the list due to the ongoing war.

One of the glaring examples of the threat to the heritage was posed by the destruction of the twin towering statues of the Bamiyan Buddhas, which stood in the Bamiyan valley for over a thousand years before their destruction in 2001 by the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. The statues were the living testimony of the lasting impact of Buddhism and the Silk Road economy that transformed Bamiyan into a meeting point of different cultures.

A year after the destruction of the statues, UNESCO sent an expedition to assess the damage and determine if the statues could be reconstructed. The team of scientists and engineers concluded that there was enough of the larger Buddha’s pieces to make a reconstruction feasible. However, the decision to reconstruct the Buddha statues has to be taken by the Afghanistan government.

The two Buddhas, 175 and 120 feet tall, were believed to be the world’s tallest standing Buddhas. Before the final act of destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas, thousands of other, smaller Buddhist statues in Afghanistan had been destroyed. The act was a defiance of the global community and a display of the Taliban’s authority in Afghanistan.

Despite strong international condemnation, the UN Security Council (UNSC) and other international efforts could not stop the Taliban from destroying the statues because the Taliban regime viewed the destruction as an internal matter and an act of political defiance and religious duty within its own sovereign territory. And the destruction proceeded.

The Stones of Bamiyan

“Their golden colour sparkles on every side,”

said a traveller of the two vast standing Buddhas.For fifteen centuries they had stood here –

towering above the valley, with their battered faces,

broken-off arms and all, undisturbed

in their cusped sandstone niches

hewn out of the sheer cliffs of the Hindu Kush,

spangled with a honeycomb of monasteries

and chanting stupas – as a stairway to heaven.“We don’t understand why everyone is

so worked up; we are only breaking stones,”

chuckled the soldiers as they blew up

the statues, leaving a gap in the world.The fabled Silk Road hangs in tatters now.

The wind howls in the poplars as it did once

when the valley was trampled underfoot

by the Great Khan and his avenging horde.Who will stop the Hun from knocking on our door?

(A poem on the Bamiyan Buddhas by R. Parthasarathy)

International bodies, including the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), tried their best to avert the destruction through diplomacy, dialogue, and legal conventions. The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) did issue a statement condemning the “incomprehensible and wanton acts of violence,” but it was not a mandate for military action or the authorisation to physically intervene on the ground.

UNESCO, the nodal UN agency for world heritage matters, for that matter, had no such power to stop the demolition as well. The Taliban was considered an isolated, non-state actor for most of the world, operating with an extreme, internal agenda that placed ideological purity above global cultural norms.

The demolition of the giant Bamiyan Buddha sculptures had shaken the International community, laying bare the limitations of existing international mechanisms for protecting cultural heritage in extremis. UNESCO indeed made multiple appeals and communication with the Taliban and with Islamic ambassadors and religious leaders, mobilised online global support and worked with organisations in Japan and Switzerland, particularly with the Afghanistan Museum in Switzerland, to stop the destruction. However, the Taliban’s political agenda under the influence of Osama bin Laden was utter disregard and hatred towards non-Islamic objects of Afghan heritage.

Furthermore, the Bamiyan Buddhas were not on the World Heritage list at the time the Taliban destroyed them in March 2001. UNESCO’s continued interest and efforts later, post-destruction, pushed for the site’s inscription on the World Heritage List only in 2003, after the Taliban’s fall, as the “Cultural Landscape and Archaeological Remains of the Bamiyan Valley” and simultaneously placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger, recognising the entire archaeological site and its landscape, not just the Buddhas that were lost.

Bamiyan’s Empty Niches: A 24-Year Warning

Culture is one of the most important elements of human endeavour, providing a sense of pride, prestige and honour to the individual, society and the nation while contributing to the development of an inclusive, innovative and resilient world in the face of emerging sustainability challenges of climate change, conflicts, poverty and achievement of most of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The heritage is our legacy from the past, what we live with today, and what we pass on to future generations.

The empty niches still stare across the Bamyam valley, a 24-year-old reminder that the 1972 Convention is a remarkable diplomatic achievement but toothless when a government (or occupying force) decides that ideology matters more than humanity’s shared memory.

In 2025, with sites in Ukraine, Yemen, Syria and beyond again under deliberate attack, the lesson of Bamiyan remains uncomfortably relevant: as long as cultural cleansing is cheaper than war crimes prosecution and sovereignty is treated as absolute, the world’s heritage will stay defenceless against those willing to erase it.

*Former UNESCO Official and Environment Specialist

What a knowledge filled masterpiece!. Thanks to Dr.Ram Boojh to pen down this thought provoking and insightful topic

My Brother Tanmay Gangopadhyay who was in Afghanistan then, went far away to the Bamiyan Budha. He wrote about it in Gujarati in a well known Gujarati Magazine.