37,000-Year-Old Bamboo Fossil in Manipur Unlocks Ice-Age Secrets

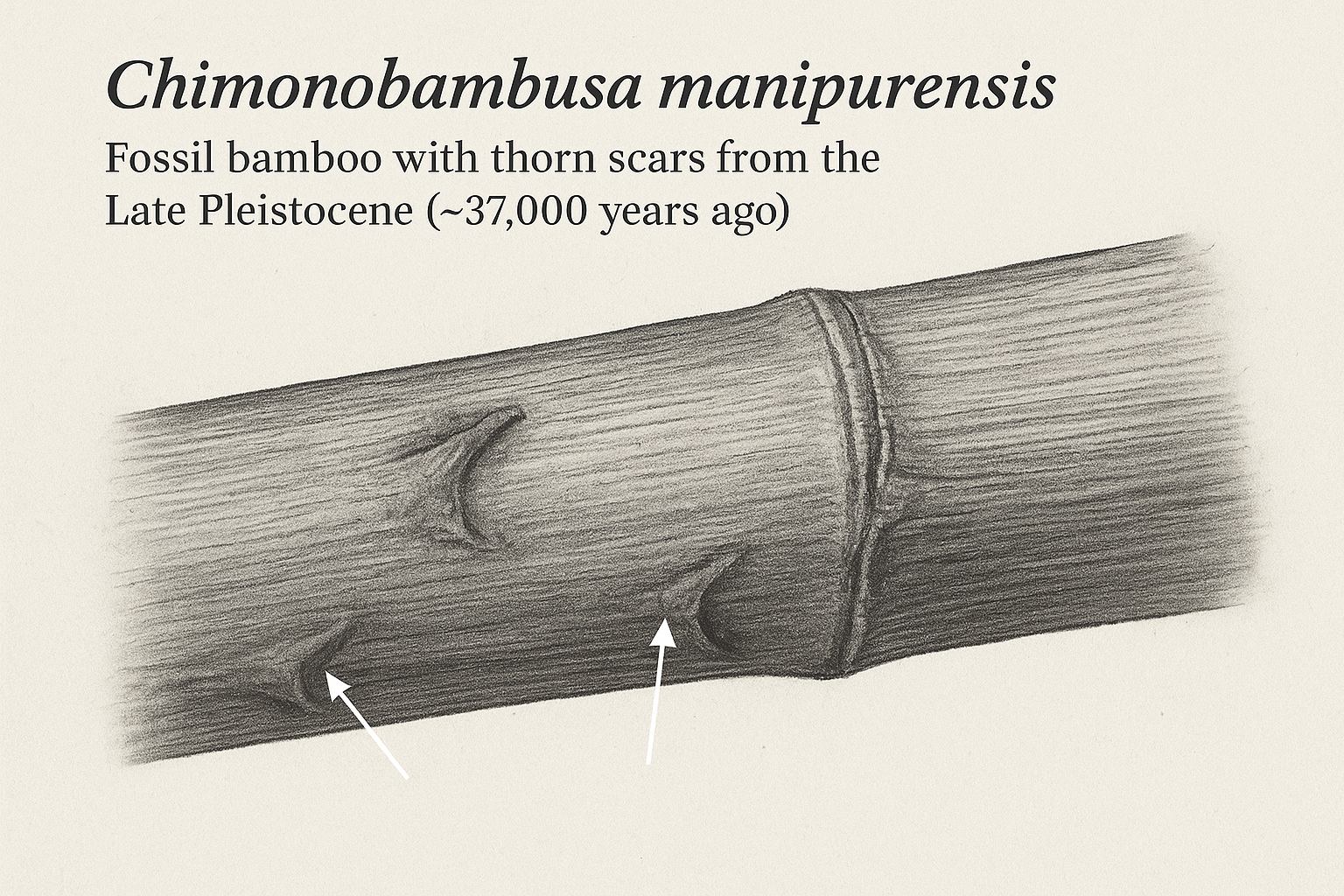

Lucknow/Imphal: A single piece of bamboo, silent and mineralised, has emerged from Manipur’s Imphal Valley after 37,000 years. It carries the faint yet sharp marks of thorns — scars left by a defence mechanism that once repelled prehistoric herbivores. Though no larger than an ordinary stem fragment, the fossil has opened a new chapter in Asian botanical history, reshaping scientific understanding of when and where bamboo evolved the ability to protect itself.

The fossil was recovered from the silt-rich floodplain deposits of the Chirang River, a tributary winding across the Imphal Valley. The site is known for sediment layering that dates back to the Late Pleistocene, a period when global temperatures were substantially lower, glaciers advanced across continents, and many plant species retreated or vanished in response to lower humidity and extended cold spells. Contrary to the typical fate of bamboo — which decays rapidly due to its hollow culm, thin cell walls and fibrous structure — this specimen survived in an unusually intact manner, preserving nodes, buds and, most strikingly, the scars of detached thorns.

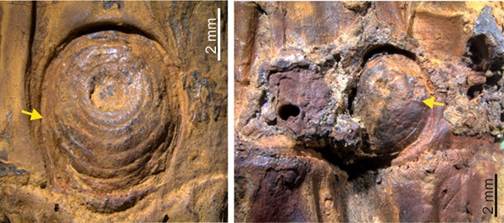

Scientists of the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP), an autonomous institute under the Department of Science and Technology (Government of India), first noticed the unusual pattern of markings during routine examination. At a distance, the stem resembled any other water-transported bamboo piece. Under laboratory microscopy, however, the researchers identified elliptical depressions and elongated attachment bases — indicators consistent with mature thornfall. Thorn scars are almost unheard of in fossil records; even in living bamboo, they disappear swiftly once the thorns break off or wither. The fact that these minute structural details survived for tens of millennia is a rarity in palaeobotany.

Based on comparative morphological assessment — including measurements of nodes, internode lengths, bud positions and thorn attachment patterns — the fossil was conclusively assigned to the genus Chimonobambusa and later established as a new species, now formally named Chimonobambusa manipurensis. Comparisons with modern thorny bamboos, such as Bambusa bambos and Chimonobambusa callosa, underscored functional continuity in defence traits: robust spines at nodes to discourage predation by herbivorous mammals.

While evolutionary theory had long assumed that thorniness in bamboo predates the Holocene, the scientific community lacked direct fossil verification. Until now, reference to prehistoric bamboo defence mechanisms has relied largely on inference from comparative analysis of extant species and their ecological niches. This newly discovered fossil provides the first unambiguous proof that thorn-bearing bamboo existed in Asia during the Ice Age.

The implications stretch beyond taxonomy. During the Late Pleistocene, bamboo disappeared from large portions of Eurasia, including Europe, as colder and drier climates reduced favourable habitats. Yet the fossil demonstrates that Manipur — and more broadly the Indo-Burma region — supported bamboo populations during the same period, acting as a climatic refuge when the plant faced drastic reduction elsewhere. The relative warmth and humidity sustained by monsoonal influence in the region appear to have provided a buffer against global extremes.

The fossil also enhances understanding of Pleistocene ecology in Northeast India. Thorniness generally arises in response to persistent herbivory, implying the presence of bamboo-grazing fauna in the region 37,000 years ago. Although the fossil itself provides no direct information about animals, the biology of bamboo suggests that the plant had acquired energy-expensive defence traits because they offered evolutionary benefits against repeated browsing pressure.

Researchers further note that the fossil’s anatomical integrity indicates rapid burial under silt — likely the outcome of a high-energy fluvial event, such as a riverbank collapse or flash flood, which sealed the stem from oxygen and biological decay. The geological context reinforces the prevailing understanding that the Imphal Valley underwent multiple flooding episodes during the Late Pleistocene, depositing thick layers of fine sediment that continue to serve as a repository of palaeobotanical material.

The discovery adds weight to a growing body of evidence demonstrating that the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot has acted as a long-term sanctuary for plant lineages through successive climatic oscillations. It also invites renewed interest in palaeoecological mapping of the Eastern Himalayas and adjoining hill systems. If bamboo survived here when it perished elsewhere, other plant groups that disappeared early from the global record may also be preserved in these deposits.

The study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, notes that further excavations could help reconstruct the vegetation history of the northeast Indian upland-valley interface during periods of high climatic volatility. Greater understanding of how plant communities persisted through extreme conditions could also inform modern conservation strategies, particularly as human-driven climate change accelerates.

Although the fossil itself is a small specimen, scientists describe it as an anchor point — one that links evolution, climate science and regional biogeography. It reminds the scientific community that life does not simply advance across the world uniformly, but sometimes survives in isolated refuges, protected by a confluence of geography, climate and ecological resilience.

For Manipur and the Indian scientific community, the finding is more than a symbolic achievement. It positions Northeast India not merely as a region rich in modern biodiversity, but also as a living archive of evolutionary memory, housing biological lineages that endured when much of the world shifted into cold dormancy.

In physical space, the fossil is only a darkened bamboo stem. In scientific time, it is a message from an era of ice, herbivores and survival — proof that adaptation was already underway long before humans ever reached the valley where the rivers still deposit silt today.

– global bihari bureau