UN’s First: Preterm Crisis in Spotlight

A New Dawn for Preterm Care—If Systems Can Deliver

Geneva: The clock struck a milestone on 14 November 2025 when the United Nations observed the first World Prematurity Day, pulling preterm birth—a silent killer of over one million neonates annually—from the footnotes of maternal health agendas into the spotlight of its own international observance.

This is not incremental progress; it is a diplomatic rupture. For years, the crisis of babies born before 37 weeks has been bundled with broader newborn campaigns, its urgency lost amid competing priorities. The designation, hammered out through advocacy by paediatricians, parent networks, and innovators in low-resource settings, elevates prematurity to the league of World AIDS Day and World Tuberculosis Day.

Governments must now report preterm-specific data, allocate dedicated funds, and implement reforms under the Every Newborn Action Plan (ENAP)—the 2014 roadmap endorsed by 194 Member States at the 67th World Health Assembly to end preventable neonatal deaths and stillbirths. The day compels accountability: preterm survival becomes a benchmark of national health performance, not an afterthought.

More than 13.4 million babies are born preterm every year—over 36,000 every day—and nearly one million die annually from complications linked not to rare syndromes but to hypothermia, respiratory distress, infections, and feeding challenges; in India, one in eight deliveries, totalling 3.5 million cases, with low birth weight claiming over 200,000 lives. Most deaths occur in the first week from hypothermia, infection, and starvation—preventable with the right interventions.

The first World Prematurity Day, formally recognised by the United Nations, arrives at a moment when premature birth has become the leading cause of death among children under five. The new UN designation is significant because it elevates prematurity, historically overshadowed by high-profile diseases, to the same global policy plane as HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis. Yet the more consequential shift is embedded in the World Health Organization’s new clinical directive that every stable preterm or low-birthweight baby should receive immediate and continuous Kangaroo Mother Care from birth. For the first time, a global guideline positions maternal skin-to-skin contact above incubators as the universal first-line intervention.

The World Health Organization’s Kangaroo Mother Care: A Clinical Practice Guide, a 140-page update to the 2003 edition, draws on a far more extensive evidence base than the 2003 edition, with global studies showing that Kangaroo Mother Care reduces neonatal mortality by 25–32 per cent, hypothermia by up to 70 per cent, severe infections by as much as a quarter, and hospital stay by three to seven days.

The World Health Organization’s Kangaroo Mother Care: A Clinical Practice Guide, a 140-page update to the 2003 edition, draws on a far more extensive evidence base than the 2003 edition, with global studies showing that Kangaroo Mother Care reduces neonatal mortality by 25–32 per cent, hypothermia by up to 70 per cent, severe infections by as much as a quarter, and hospital stay by three to seven days.

Although preterm births account for only about 7.2 per cent of all births worldwide, they are responsible for more than 18 per cent of under-five deaths. Economic examinations place the annual cost of prematurity at USD 16 billion in direct medical and societal losses in high-income countries alone. Comparable losses in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa remain largely uncalculated but are expected to be significantly higher because they include prolonged disability, developmental delays, and income losses among caregivers.

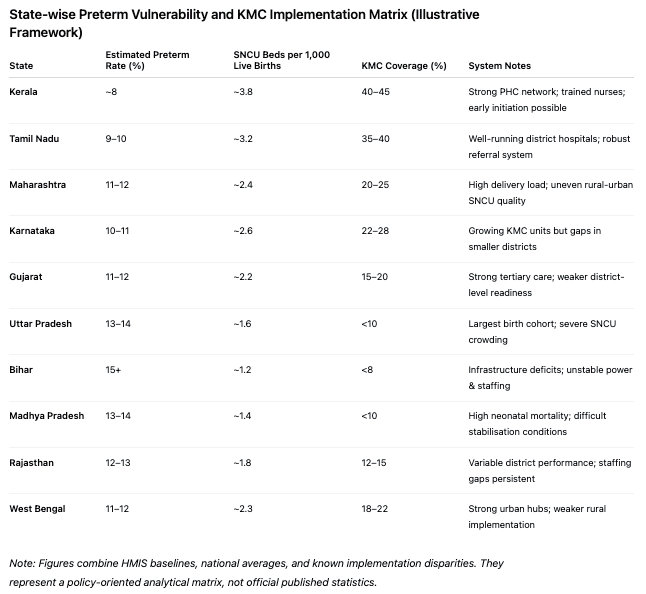

India stands at the centre of this global crisis, with approximately 3.5 million preterm births annually, representing more than a quarter of the world’s total. One in eight Indian babies is born too soon. The burden is not uniform: Kerala’s prevalence is close to 8 per cent, supported by robust primary health centres, while states such as Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Madhya Pradesh cross 15 per cent and sometimes approach 17 per cent. Maternal anaemia, which affects around 57 per cent of Indian women, remains the most widespread risk factor, supplemented by adolescent pregnancies, untreated urinary tract infections, and inadequate antenatal care. Prematurity alone accounts for nearly a quarter of neonatal deaths in the country. Low birthweight contributes to additional mortality, particularly in rural districts with limited referral capabilities.

Even nations with weaker health systems have begun institutionalising early KMC bays, while India — despite possessing one of the largest public health infrastructures in the world — continues to rely heavily on Special Newborn Care Units (SNCU)–first pathways, which delay the moment when infants receive the one therapy that demonstrably stabilises them fastest: parental warmth and continuous skin-to-skin contact.

The WHO directive for immediate Kangaroo Mother Care highlights the gap between scientific consensus and practical capacity. Continuous KMC ideally requires 24 hours of skin-to-skin care daily, with eight hours considered the minimum threshold for measurable benefit. Yet in India’s public hospitals, postnatal stays often do not exceed 48 hours, nurse-to-infant ratios in Special Newborn Care Units frequently reach 1:30, and nearly one in three births is delivered by Caesarean section, making prolonged skin-to-skin contact difficult. Facility-readiness indicators reflect wide disparities: Kerala maintains roughly 6 to 7 SNCU beds per 1,000 live births; Tamil Nadu and Karnataka cluster around 5; Maharashtra ranges between 4 and 5; while Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and Madhya Pradesh often fall below 3, with several districts chronically overstretched. When these densities are placed alongside state-wise preterm prevalence and Kangaroo Mother Care coverage, a clear implementation matrix emerges, showing that high-burden states frequently have the lowest KMC readiness and the poorest follow-up systems.

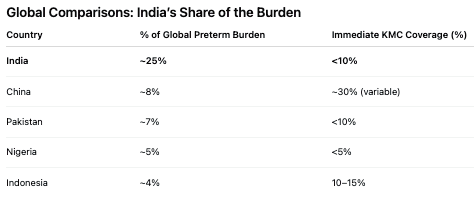

International comparisons further contextualise the challenge. Sub-Saharan Africa records 40 per cent of global preterm deaths and South Asia 34 per cent. Survival for infants under 1,500 grams exceeds 90 per cent in Japan, Sweden, and South Korea; the same weight category registers survival below 15 per cent in parts of Africa and below 25 per cent in India’s most resource-constrained districts. Despite evidence that Kangaroo Mother Care is one of the most cost-effective interventions—global models suggest that every dollar invested yields up to thirty dollars in savings from reduced hospitalisation and long-term disability—nationwide adoption remains limited. Only 39 countries report nationwide KMC programmes, and fewer than 10 per cent offer immediate KMC from birth. Global comparisons make the contrast sharper: India accounts for nearly 25 per cent of the world’s preterm births but provides immediate KMC to fewer than 10 per cent of eligible newborns, placing it far below countries like Colombia and Vietnam, where KMC originates and where early coverage exceeds 60 per cent.

India’s research portfolio presents a layered picture of both promise and fragility. The Community-Initiated KMC trial in rural Haryana, involving more than 4,000 low-birthweight infants, documented a 10–15 per cent mortality reduction through home-based KMC delivered for at least eight hours daily under the guidance of trained community health workers. However, adherence declined sharply where mothers lacked household support or faced pressure to resume domestic responsibilities. The Immediate KMC Implementation Study conducted across Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, and Haryana produced a 40 per cent increase in KMC uptake and a 25 per cent mortality decline among infants under 2,000 grams in Sonipat, yet uptake plateaued around 60 per cent in rural blocks. Power outages, incubator downtime, and staff shortages often pushed facilities to rely on KMC not by protocol but by necessity, complicating the attribution of outcomes to intentional implementation.

Other Indian evaluations expose similar tensions. A 2023 Tamil Nadu–Karnataka qualitative study recorded emotional benefits for 85 per cent of mothers practising KMC, with exclusive breastfeeding rising by more than one-third, but only half the participants sustained KMC beyond two weeks. A 2022 quality improvement initiative at Chengalpattu Medical College raised average KMC hours from 2.5 to 7.5 daily and lowered infections by 20 per cent, although staff rotation across departments made such improvements difficult to maintain. In the Anand district of Gujarat, 65 per cent of doctors surveyed were aware of KMC, but fewer than half could correctly demonstrate safe binder positioning or airway protection. Continuity of care emerged as a recurrent gap, especially in districts where community follow-up visits are irregular or limited by terrain and staffing.

Economic comparisons underscore the magnitude of possible system savings. A functional incubator costs between ₹5 lakh and ₹15 lakh, excluding maintenance and electricity, while creating a fully equipped KMC ward—reclining chairs, washable binders, privacy partitions, dedicated maternal beds—costs less than ₹3 lakh. Early KMC-supported discharge can save between ₹2,000 and ₹6,000 per infant in public facilities. A longitudinal cost model based on district-level caseloads shows that widespread KMC adoption could reduce Special Newborn Care Unit congestion by 20–35 per cent over three years, lowering electricity consumption, maintenance expenditure, and incubator replacement cycles. Nationally, universal KMC coverage is estimated to prevent as many as 450,000 infant deaths annually and reduce hospital expenditure by billions.

The WHO guidelines emphasise the need for infrastructural redesign. Integrated mother-newborn care units that position maternal beds alongside equipment-intensive spaces aim to end the long-standing separation of mothers and newborns, yet implementation remains sporadic. India has more than 700 district hospitals and roughly 35,000 primary health centres; converting even a fraction of them into KMC-ready facilities requires long-term capital planning. Expanding a typical neonatal wing to include fifty maternal beds requires around 1,500 square feet and recurring operational costs for sanitation, linens, and support staff. The absence of such dedicated spaces in most facilities is one of the strongest structural barriers to continuous KMC.

Global research strengthens the argument for accelerating adoption. A 2023 review of thirty international trials found that Kangaroo Mother Care reduced postpartum depression among mothers by nearly a quarter and enhanced paternal bonding when fathers were encouraged to participate. Continuous KMC has reduced hypothermia by up to 60 per cent in Ethiopia, Malawi, and Nepal during nights when ambient temperatures fell below 15°C, often outperforming radiant warmers during power outages. Colombia’s long-running programme shows better cognitive outcomes and fewer hospital readmissions in infancy. These findings are echoed in data from Bangladesh, where early KMC reduced sepsis by nearly 30 per cent in community settings.

Follow-up studies show uneven results depending on infrastructure. St John’s Medical College in Bangalore reduced hypothermia by 70 per cent after adopting continuous KMC, but community trials in Delhi recorded only around 40 per cent improvement. The WHO acknowledges these inconsistencies through detailed annexes on airway safety, breastfeeding support, growth monitoring, micronutrient supplementation, and community follow-up. The guideline notes that more than 70 per cent of births in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa still occur in facilities without full neonatal support, making community continuity essential to achieving any sustained benefit.

The fundamental tension is clear. Kangaroo Mother Care is physiologically superior for most stable preterm infants, yet it depends on caregiver time, social support, and health-system readiness. Incubators remain essential for the sickest newborns but are vulnerable to power instability, maintenance failures, and infection risks in overcrowded facilities. The WHO does not advocate replacing incubators; rather, it proposes a hybrid model in which stable infants receive skin-to-skin care while technology is prioritised for those who genuinely require it. Where health systems embrace this hybrid model, survival tends to rise rapidly; where the model is under-resourced, gains remain inconsistent and fragile.

As the world observes the first official World Prematurity Day, the symbolism is strong, but the task ahead is more substantive. Survival for the smallest babies will depend on whether health systems can translate evidence into practice by redesigning wards, training staff, strengthening community linkages, and supporting families through the social pressures that impede continued Kangaroo Mother Care. In India—where premature births remain high and public hospitals operate under severe strain—the challenge is no longer conceptual but political, logistical, and urgent.

– global bihari bureau