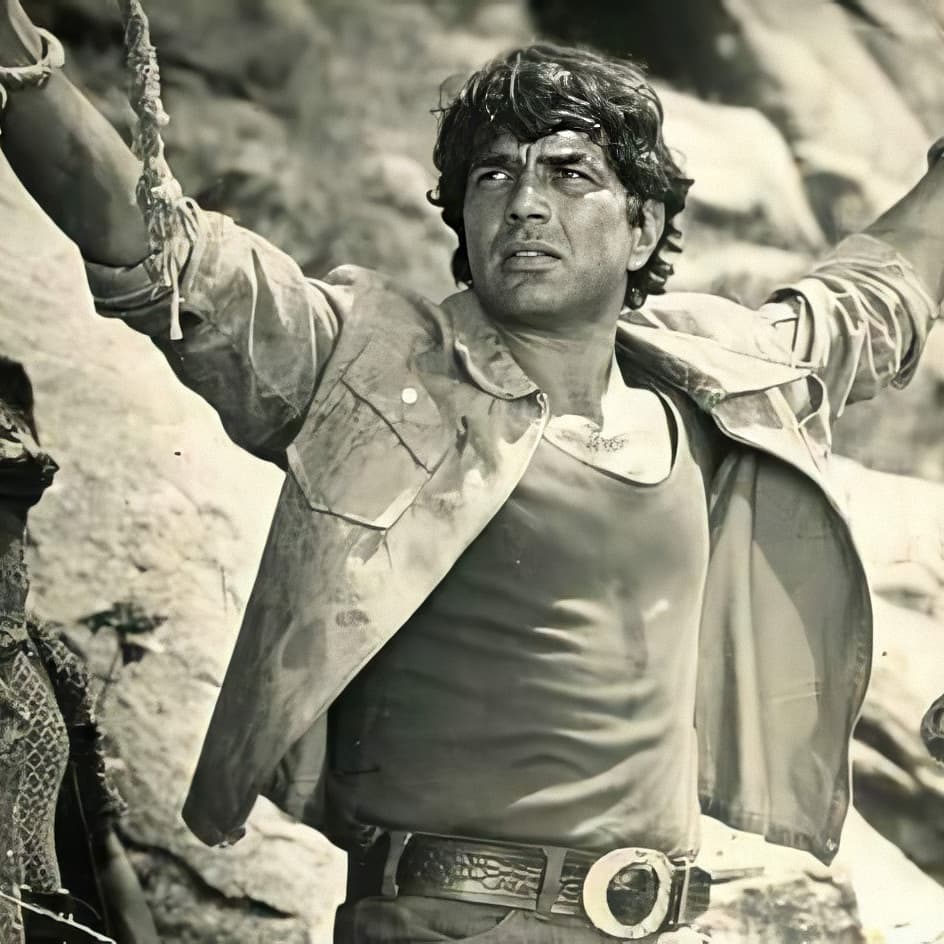

Dharmendra in Sholay

By Deepak Parvatiyar*

By Deepak Parvatiyar*

Dharmendra’s Legacy: Hits and Heart

The news arrived quietly, the way Dharmendra himself always preferred to leave a room, no dramatic exit, no final close-up, just a gentle fade to black. At his beloved Lonavala farmhouse, surrounded by the fields he had tilled with his own hands in the last decades, Dharmendra Kewal Krishan Deol, the boy who would become Bollywood’s unbreakable “He-Man,” the thunderous voice behind “Kutte, kaminey, main tera khoon pee jaunga,” and the tender soul who once bribed spot boys with pocket change just for one more hug on the sets of Sholay, slipped away at the age of eighty-nine, two weeks short of ninety, from the quiet accumulation of years that even the He-Man could not outrun.

Off-screen, Dharmendra was the anti-hero: humble as harvest moon, humorous as a hidden flask. “Growing up, Dharmendra ji was the hero every boy wanted to be,” Akshay Kumar tweeted today, voice cracking in memory. Madhuri Dixit called him “one of the most handsome persons I’ve seen,” Jaya Bachchan a “Greek God.” Zeenat Aman remembered his set-side modesty: “Strikingly handsome, yet he’d ease my nerves with village tales.” A Sagittarius adventurer, he embodied courage with kindness – loyal to the bone, generous to a fault, his 100-acre Lonavala haven a testament to rooted wanderlust. “I’m no artifice,” he once said. “Just a boy who loves laughing loud and living true.”

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi captured the world’s grief, “The passing of Dharmendra Ji marks the end of an era in Indian cinema. He was an iconic film personality, a phenomenal actor who brought charm and depth to every role.” From Amitabh Bachchan’s tear-streaked nod to their unbreakable Sholay bond – “Yeh dosti hum nahi todenge” – to Rajinikanth’s raw whisper of “A golden heart… Farewell, my friend,” the tributes cascade like monsoon rains, washing over a legacy that doesn’t fade; it ferments, growing richer with every retelling.

Let’s rewind the reel to Nasrali village, Ludhiana, where Dharmendra was born in a small mud-brick house on 8 December 1935. The son of a strict school headmaster who wanted him to become an officer or at least a respectable clerk, little Dharam Singh Deol chased shadows of heroes across mustard fields, while his father, Kewal Krishan, preached the gospel of steady jobs over starry delusions. “My father was shocked when I said I wanted to be an actor,” Dharmendra later reminisced in a heartfelt chat, his voice carrying that signature rumble laced with boyish wonder. “He thought marriage would settle me, but the film bug had bitten deep – ever since I snuck into a screening of Shaheed and watched Dilip Kumar command the screen like a king.” By 1952, after matriculating in Phagwara and flirting with Panjab University, Dharam was drilling for an American oil company, saving every paisa for Filmfare magazines that arrived like forbidden love letters. “I devoured them,” he confessed in a 1997 acceptance speech, eyes twinkling under stage lights. He lied to his mother, told her he was going to Jalandhar for a job interview, and instead took the Frontier Mail to Bombay with eighty rupees and a photograph for the Filmfare-Guru Dutt-Bimal Roy talent contest.

Bombay did try. It starved him, humiliated him, made him sleep on footpaths and write his Hindi lines in Gurmukhi on cigarette packets. Yet every time it pushed, he pushed back harder, with a smile that could melt studio lights. The first cheque he ever earned, fifty-one rupees for Dil Bhi Tera Hum Bhi Tere, he framed and hung above his bed for seventy years. From that tiny room in Dadar to the hundred-acre farm where he died, every brick, every tree, every cow was bought with the sweat of a man who refused to let the city win.

And win he did, gloriously, thunderously, tenderly. In the six and a half decades that followed, he devoured the industry and gave it back a hundredfold: over three hundred films, seventy-four certified hits, six all-time blockbusters, four consecutive years (1972–75) as Box Office India’s undisputed number one, and two separate calendar years (1973 and 1987) in which he delivered seven hits each, records that still stand like ancient oaks no new storm has managed to uproot.

He arrived speaking no Hindi, only Punjabi, and learned his lines by writing them in Gurmukhi on scraps of paper he hid in his palm. His first paycheck was fifty-one rupees, seventeen each from three producers who had pooled the money for Dil Bhi Tera Hum Bhi Tere. He kept that cheque framed for the rest of his life. From there the climb was meteoric: the sensitive doctor in Bandini who made Nutan weep, the doomed soldier in Haqeeqat, the bare-chested saviour in Phool Aur Patthar that turned him overnight into the He-Man, the tragic idealist of Satyakam who won him a National Award, the comic genius of Chupke Chupke who could make Hrishikesh Mukherjee double up with laughter between takes, the thunderous dacoit-hunter of Mera Gaon Mera Desh, the lost-and-found brother of Yaadon Ki Baaraat, and, above everything else, Veeru of Sholay, the role he always insisted was not acting at all, just Dharmendra with a garam coat and a heart the size of Punjab.

Five times the Filmfare Best Actor trophy slipped through his fingers, once for Phool Aur Patthar, then Mera Gaon Mera Desh, Yaadon Ki Baaraat, Dost, Resham Ki Dori, and once more in Supporting Actor for Ayee Milan Ki Bela. Every year, he would polish his shoes, choose a tie that matched his suit, and sit in the audience thinking, “Aaj toh mil jaayega.” It never did. When they finally handed him the Lifetime Achievement Award in 1997, he bounded up the stage, hugged Dilip Kumar, and laughed through tears: “Thirty-seven years I wore a matching tie and suit, and tonight God compensated by giving me fifteen trophies in one go!”

He never chased awards, he said; he chased truth. And truth, for him, was often found in a beer bottle disguised as lassi on the sets of Sholay. Ramesh Sippy would tear his hair out because Dharmendra would finish twelve bottles a day and still deliver the water-tank suicide scene in a single take. The real secret, he confessed decades later, was that every time Hema Malini had to embrace him for the shot, he quietly slipped twenty or fifty rupees to the spot boys with whispered instructions: “Light gir jaayegi, reflector hil jaayega, ek aur take!” He spent almost two thousand rupees just for extra hugs. “Best investment I ever made,” he would say, eyes twinkling.

Love, for Dharmendra, was never simple. Married at nineteen in an arranged ceremony to Prakash Kaur, a woman he described as “pure gold,” he became father to Sunny, Bobby, Vijeta, and Ajeeta. Yet when he met Hema Malini at a premiere, something irrevocable shifted inside him. “The first time I saw her I told my friend, ‘Yaar, yeh ladki meri hogi.’” Twenty films, countless stolen glances, and one legendary interrupted wedding later (he flew to Madras with Shobha Sippy to stop Hema’s mother from marrying her off to Jeetendra), they were wed in 1980 in a quiet Iyengar temple with only four witnesses. Rumours of conversion to Islam dogged them for decades; he dismissed them with the same calm shrug he used for everything that tried to diminish him: “I never changed my name, never changed my faith. I only changed my heart’s address.” Prakash Kaur, in one of the most dignified statements ever made by a wronged wife, told Stardust in 1981, “Dukh toh hota hai, lekin main us dukh ko apne andar daba leti hoon. He may not be the best husband, but he is the best father.” When Dharmendra read those words, he wept like a child. Branded a “womaniser” by tabloids, he faced public scorn, yet Prakash Kaur defended him fiercely in the 1981 Stardust interview: “Why only my husband? Any man would have preferred Hema over me… All heroes are having affairs…”

From that complicated union came Esha and Ahana, and somehow, against every prediction of the gossip columns, the two families found a way to coexist. When Esha was old enough to ask questions, Hema sat her down and explained gently. There were no screaming matches, no public mud-slinging, only quiet acceptance and the knowledge that Dharam Paaji’s heart was large enough to hold everyone. The two families stitched themselves into one patchwork quilt held together by his boundless heart. Hema, years later, would say simply, “He never lied to me, never promised what he couldn’t give. He just loved, completely, clumsily, the only way he knew how.”

When the grandchildren came, they called both women Dadi, and no one corrected them.

In the final weeks, when machines breathed for him in Breach Candy, Sunny and Bobby stood guard like the heroes he had raised them to be, Esha and Ahana held their mother’s hand, and Prakash and Hema took turns sitting by his bedside. The Deol dynasty, fractured on paper, proved unbreakable where it mattered. Outside, the paparazzi screamed for pictures; inside, six children kept vigil for the man who had taught them that real strength is the courage to be vulnerable.

He launched his sons the way only a father who had once stood penniless at Dadar could: Sunny with Betaab, a debut that earned seventeen crore when seventeen crore was real money, and Bobby with Barsaat, both under his banner Vijayta Films. “I never forced them,” he said on Koffee with Karan. “I only told Sunny, ‘Ek film kar lo, pasand na aaye toh England wapas jaana.’ The public made him a star in one night.” He produced Ghayal, the film that swept seven Filmfare and a National Award, because he believed his son’s anger on screen was the same anger he himself had carried from the villages into the city.

In his seventies and eighties, he reinvented himself yet again: the lonely husband in Life in a… Metro, the mischievous patriarch in Yamla Pagla Deewana, the progressive grandfather in Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani, still handsome enough that Alia Bhatt blushed on set and Ranveer Singh called him “the original Greek God of Bollywood.” Even in 2025, battling corneal transplants and breathing trouble, he sent a voice note from his hospital bed when fake death news went viral: “Arre bhai, marne ka bhi ek style hota hai, itna jaldi thodi na marunga!” Three weeks later, he kept his promise, no fuss, no cameras, just family and the quiet of his farm.

He hated birthdays in his later years. “I cry alone remembering Ma,” he told Filmfare in his last major interview, “then I go plant a few trees, feed the cows, and feel happy again. Life has given me everything: love, fame, two beautiful families, and grandchildren who call me Dadaji He-Man. What more can a village boy ask for?”

He asked for nothing more and gave everything. When the end came, there was no dramatic last line, no slow-motion walk into the sunset. Just the soft closing of a door on a life that had already provided Indian cinema with enough slow-motion, enough sunsets, enough heart-stopping dialogues to last a thousand years.

Dharmendra’s legacy? It’s the pulse of Bollywood – the man who fused rural rawness with urban gloss, birthing the action-romance hybrid that still powers Khans and Kumars. Ranked 10th on Rediff’s all-time greats, his seven-hit years (1973, 1987) stand unbroken.

As he himself once said, laughing that unmistakable laugh: Picture abhi baaki hai, mere dost.

The garam coat is finally off, Paaji. But somewhere tonight, a spot boy is still waiting for his fifty-rupee note, a reflector is about to fall, and Veeru is climbing that water tank one more time, grinning, because Basanti is waiting with open arms.

Om Shanti! Thank you for every extra take, every thunderous laugh, every quiet tear, and every hug you bribed the world to give us. The He-Man has ridden into eternity, but the fire still burns. Forever.

*Senior journalist