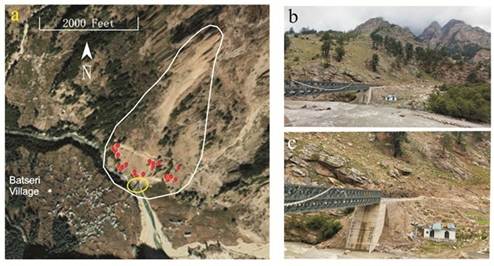

(a) Red dots indicate location of collected, rock fall-impacted Cedrus deodara trees from a hazard prone slope (catchment area indicated with white lined area) opposite to Batseri village. The yellow circle indicates the location of a bridge and a house damaged by a rockfall in July 2021. (b) View on the rockfall prone slope and Deodar trees. (c) Damaged house and reconstructed bridge after damage in July 2021.

Dry Springs, Deadlier Slopes: Kinnaur’s New Warning

Tree Rings Warn of Rising Geohazards in Kinnaur

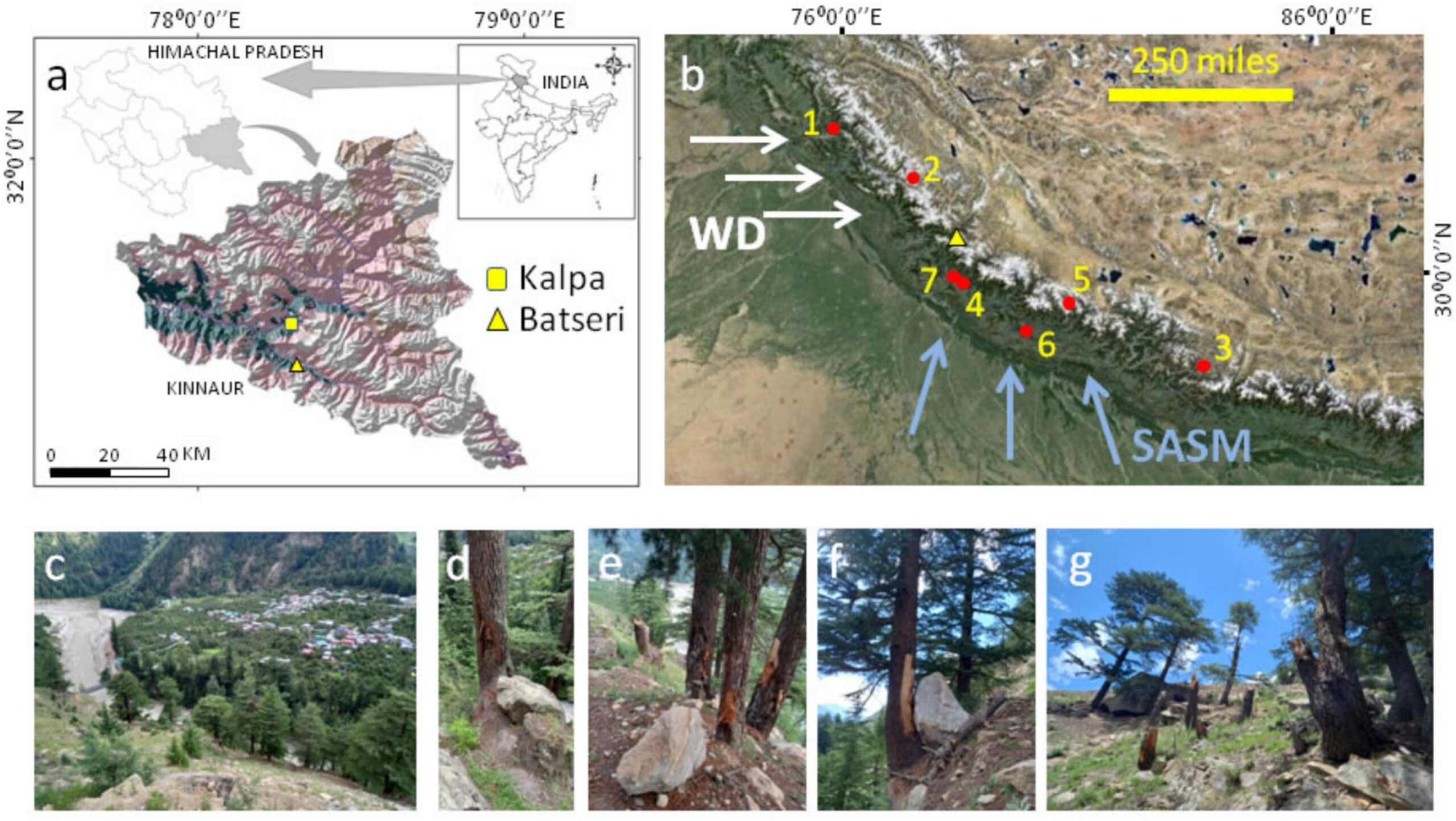

Lucknow: High above Batseri village in Himachal Pradesh’s Sangla valley, the silent Deodar trees have been keeping a centuries-long diary of the Himalayan climate. Now, scientists have learned to read it. In their tightly packed rings — carved year after year into slopes scarred by rockfalls — researchers from the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences (BSIP) have uncovered nearly 400 years of shifting moisture, worsening droughts and rising geohazard activity that shape life in the fragile western Himalayas.

The discovery began with disaster. In July 2021, a sudden rockfall near Batseri smashed a bridge and damaged a house on the Baspa River’s banks. When scientists climbed the slope opposite the village, they found not just boulders and debris but trees gashed, twisted and broken by past rockfall episodes. Those injuries became clues, allowing researchers to merge tree-ring climatology with geomorphology to piece together a long-term record of both climate variability and slope instability.

Their work produced two landmark reconstructions: a 378-year timeline of spring moisture (1558–2021 CE) and a 168-year record of rockfall events (1853–2021 CE). The results reveal that the region’s spring climate shifted dramatically after 1757 CE, moving from the wetter conditions characteristic of the Little Ice Age to increasingly dry springs in the modern era. The trees showed heightened sensitivity to moisture in February–April months governed by winter precipitation from Western Disturbances — making them reliable witnesses of hydroclimatic change.

What the tree rings spell out is a clear link between climate stress and geohazard risk. The scientists identified 53 rockfall events, including eight major ones, many clustered after 1960 when dry spring years began rising sharply. When spring drought strips slopes of moisture and vegetation, the terrain becomes brittle; all it takes then is heavy monsoon rain to trigger destructive rockfalls. Images from the study show scarred slopes, injured Deodars and the damaged structures from 2021 — visual reminders of how closely Himalayan settlements live with danger.

The implications extend far beyond Batseri. As extreme events — droughts, cloudbursts, floods, GLOFs, avalanches — intensify under a warming climate, the Himalayas face compounding risks. Yet long-term, high-resolution records of moisture variability and hazard frequency have been scarce. This study, published in Catena, fills that gap by creating a climate–hazard archive from natural indicators that continue to grow and record every passing year.

The findings strengthen the case for better forest and slope management, targeted land-use planning, improved water governance and early warning systems tailored to Himalayan terrains. For communities already confronting climate volatility, such science offers more than historical insight — it offers a basis for practical preparedness. And for policymakers, it demonstrates the value of reading the signals the mountains have been sending for centuries, etched in wood by trees that have endured every drought, storm and rockfall before the next one arrives.

– global bihari bureau