Invisible Bugs Thrive in Delhi’s Toxic Skies

Delhi’s Pollution Fuels Bacterial Health Risk

Kolkata: Delhi’s choking air is not just a pollution crisis but a breeding ground for invisible bacteria, doubling the risk of infections in the city’s densely packed neighbourhoods, a new study warns. Released on September 2, 2025, by the Kolkata-based Bose Institute, the research reveals that airborne pathogens, hitching a ride on microscopic dust particles, thrive in the capital’s polluted skies, posing a silent threat to millions and urging a rethink of urban health strategies.

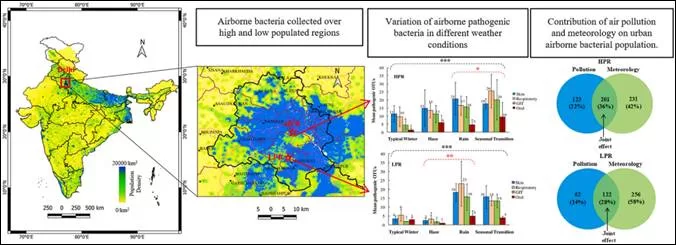

The term “airborne pathogens” refers to bacteria that cause respiratory, gastrointestinal, oral, and skin infections, carried through the air on PM2.5 particles—fine dust small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs. The study, published in Atmospheric Environment: X and led by Dr. Sanat Kumar Das of the Bose Institute, found these pathogens are twice as abundant in Delhi’s high-population zones compared to less crowded areas. “The cocktail of pollution and weather patterns creates a perfect storm for microbes to linger longer,” Dr. Das said, highlighting how winter conditions amplify the risk.

Conducted in the Indo-Gangetic Plain (IGP), one of the world’s most densely populated and polluted regions, the study pinpointed Delhi as a hotspot. The city, home to over 20 million, ranks among the world’s most polluted urban centres. During winter, western disturbances lower temperatures and raise humidity, trapping pollutants in a low boundary layer with stagnant winds. This environment allows PM2.5, laden with pathogens, to accumulate, increasing infection risks. “PM2.5 acts as a carrier, sneaking bacteria into the lungs and spreading disease,” Dr. Das explained, noting that hazy days and winter rains create “high-risk windows” for outbreaks.

The study’s findings are a wake-up call for Delhi, where air quality routinely breaches hazardous levels. In 2024, Delhi’s Air Quality Index (AQI) frequently exceeded 300, classified as “severe” by the Central Pollution Control Board, with PM2.5 levels often surpassing WHO safety limits by 10–15 times. The research shows that densely populated areas, like Old Delhi and East Delhi, harbour twice the microbial load compared to greener, less crowded zones like Lutyens’ Delhi. This disparity underscores how population density and pollution amplify health risks, particularly for vulnerable groups like children and the elderly.

Dr. Das emphasised the need for action: “Understanding how pollution and weather drive bacterial spread can help predict outbreaks and guide urban planning.” The study suggests integrating microbial monitoring into air quality frameworks and redesigning cities to reduce pollution hotspots. However, challenges loom—India’s air quality management is underfunded, and Delhi’s rapid urbanisation strains infrastructure. Retrofitting a megacity for better ventilation and green spaces is costly, and public health systems may struggle to handle potential infection surges.

The report calls for urgent policy shifts, including real-time air quality alerts tied to microbial risks and stricter emissions controls. With Delhi’s population projected to hit 23 million by 2030, the stakes are high. Failure to act could exacerbate respiratory and gastrointestinal disease burdens, already significant in India, where 1.5 million deaths were linked to air pollution in 2021, per WHO estimates. The study’s insights could reshape urban health strategies, but implementation hinges on overcoming logistical and financial barriers in a city battling chronic pollution.

The launch, attended by Department of Science and Technology officials, underscores the government’s push for science-driven solutions. Yet, with winter approaching, Delhiites face an immediate threat from this invisible enemy, demanding swift action to protect public health.

– global bihari bureau