By Deepak Parvatiyar*

By Deepak Parvatiyar*

Noise That Kills: India’s Silent Epidemic

Delhi to Varanasi, and Kashmir to Kanyakumari, the racket never stops — it just changes pitch. In the biting December of 2025, when cities are already choking on smog, noise pollution has once again raised its head, only to be politely ignored.

On December 6, 2025, a four-member team from Satya Foundation, an outfit that has been fighting noise since 2008, walked into the office of Varanasi Police Commissioner Mohit Agarwal and handed over a memorandum. Their simple demand: equip every police station and chowki in the commissionerate with decibel meters. If granted, Varanasi would become the first district in Uttar Pradesh where every cop on the beat can actually measure noise instead of just shrugging. The Commissioner heard them out, read the letter, and promised “serious consideration”. Anyone who has followed such promises knows exactly how that movie ends.

This little episode in a holy city is only a speck in a nationwide picture where Indian cities are drowning in noise.

According to the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) standards, residential areas are entitled to 55 dB by day and 45 dB by night. Reality laughs at those numbers. The National Ambient Noise Monitoring Network (NANMN), running since 2011 across 35 stations in seven metros, shows the same old story in its 2023-24 reports (2025 data still “under compilation”): Delhi clocks 65–75 dB in the daytime and routinely touches 60 dB after dark; four out of five stations in Mumbai and Bengaluru breach limits, especially at night.

In 2025, 23 out of 26 Delhi monitoring stations exceeded permissible levels during Diwali, with daytime readings ranging from 49.3–93.5 dB(A) — a stark rise from 2024’s 88.7 dB(A) night average. Moradabad in Uttar Pradesh was flagged in a 2022 United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report for high peaks (114 dB), though disputed by local officials as possibly flawed or misattributed, highlighting South Asia’s urban noise hotspots. Right to Information (RTI) replies reveal that state pollution boards are sitting on mountains of unprocessed data — Uttar Pradesh, for instance, hasn’t released Q1 2025 figures yet, amid 49% staff vacancies (355 out of 732 posts) as per August 2025 RTI responses.

The World Health Organization (WHO) quietly notes that 93 per cent of India’s urban population lives with chronic noise exposure in a country that already carries over 101 million diabetes and 314 million hypertension cases.

These noise figures are not raw peaks but Leq values — the equivalent continuous sound level, A-weighted, which averages fluctuating noise over a defined period into a single steady value, capturing total acoustic energy. CPCB methodology specifies Leq over daytime (6 a.m.–10 p.m., 16 hours) and nighttime (10 p.m.–6 a.m., 8 hours), using A-weighted decibels (dB(A)) to mimic human ear sensitivity. Peaks (Lmax) can spike 20–30 dB higher during festivals or rush hours, but Leq better reflects chronic exposure.

Varanasi demands meters, silence demands justice

Satya Foundation’s memorandum spells out why a ₹6,000 decibel meter in every thana matters. Under the Noise Pollution (Regulation and Control) Rules, 2000, read with the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986, all loudspeakers must be switched off between 10 p.m. and 6 a.m. — no meter needed; police can seize equipment and file cases straightaway. Yet between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m., limits exist on paper but enforcement collapses because most patrol teams have no way to prove the breach. Result: walls crack from vibration, heart attacks spike, and complaints die in the diary. The Foundation also wants night patrol squads that act suo moto after 10 p.m. (because “influential” violators simply switch the music back on once the beat constable leaves) and a written circular to every station that “just one day” or “religious sentiment” is no excuse for breaking the night silence rule.

70 dB by day, 55 dB by night: Delhi’s new normal

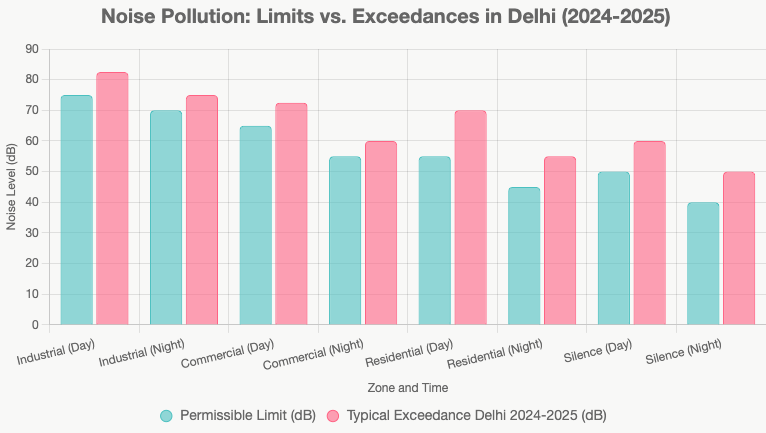

Noise hits hardest where people live — and unequally. In Delhi, traffic corridors like ITO or Anand Vihar average 80–85 dB Leq during the day, driven by honking and idling engines, while quieter residential pockets in South Delhi hover at 65–70 dB. Mumbai’s informal settlements near Dharavi or Byculla slums report 75–80 dB from mixed sources (traffic, generators, street vendors), exceeding commercial zone limits by 10–15 dB, with peripheries like Navi Mumbai edging lower at 60–70 dB but still breaching residential norms. Nighttime drops 5–10 dB across zones, but informal areas lag due to unregulated night markets. The numbers are merciless. Here is Delhi’s everyday truth (estimated 2024–2025 Leq averages, day/night, based on NANMN trends and DPCC monthly reports):

In plain language: where the law allows 55 dB by day and 45 dB by night, Delhi delivers 70 and 55. That extra 10–15 dB is the slow poison that causes permanent hearing loss, spikes cortisol, pushes up blood pressure, triggers heart disease, diabetes, anxiety, depression, and sleep bankruptcy. Indian studies sharpen the edge: a Delhi-based ecological analysis linked higher Leq noise (above 65 dB) in rural-urban fringes to a 15–20% rise in cardiovascular admissions, correlating with hypertension spikes. Another cohort in Mumbai found road traffic noise (Leq >70 dB) associated with 8–12% higher hypertension prevalence among low-income groups, compounding air pollution effects. Urban workers exposed to 75+ dB report 25% more arrhythmia cases, per a 2023 Science of the Total Environment study. The young are losing hearing faster than ever before; noise exposure during pregnancy may contribute to lower birth weights (often in synergy with air pollution like PM2.5), per global reviews and some Indian studies; birds in city parks have changed their songs because they can’t hear themselves no more.

Festivals, faith and noise: Rules bend, hearts break

The legal armoury looks impressive on paper — Environment Protection Act, 1986; Noise Rules, 2000; Supreme Court orders of 2024 declaring excessive noise a violation of Article 21 — yet the ground reality is a yawn. Enforcement? Spotty at best. In 2024–25, Delhi police registered over 5,000 noise complaints via 112 helpline and apps like Green Delhi, but prosecutions numbered under 200 — mostly for loudspeaker misuse during festivals, with fines averaging ₹5,000–10,000 (max ₹1 lakh under the Act).

Maharashtra Pollution Control Board (PCB) issued 300+ fines in 2024 for Ganesh Chaturthi violations (peaks >80 dB), but recovery hovers at 40% due to appeals. Only 15% of NANMN stations have real-time IoT gear; most rely on manual spot-checks. Bombay HC’s January 2025 guidelines mandated “silent zones” around hospitals with ₹1,000–2,000 honking fines, but compliance audits show 60% evasion in informal areas. Maharashtra PCB recorded peaks above 80 dB during Ganesh Chaturthi 2024; nothing changed. Newspapers write editorials, experts demand IoT monitors and green buffers, apps like Green Delhi collect complaints by the thousand, but the chain of enforcement — state boards, police, municipal bodies — remains happily fragmented.

So here we are, December 2025: one small NGO begging for decibel meters in Varanasi, while the rest of the country continues to treat noise as an inevitable side-effect of “culture” and “development”. The meters may or may not arrive. The noise certainly will — louder, longer, and deadlier — until the day we finally admit that the right to silence is also a right to life. Until then, keep the earplugs handy.

*Senior journalist