Forests Hold the Keys to Climate-Proofing Agriculture

Study Shows Forest Loss Undercuts Global Food Systems

Belém, Brazil: As the 2025 United Nations Climate Change Conference (Conference of the Parties 30, COP30)unfolds in the Amazonian city of Belém, one message from scientists and negotiators is emerging with uncommon clarity: agriculture cannot be climate-resilient without healthy forests. The conversation around forests is undergoing a profound realignment. The science presented here shows that forests are not just carbon reservoirs or biodiversity sanctuaries but active engines propelling agricultural success.

A new report led by the FAO, launched at the conference, underscores that climate-resilient farming depends on the ecological functions performed by forests and trees, from cooling land surfaces and sustaining rainfall to regulating water flows, reducing soil loss and protecting rural workers from life-threatening heat. The findings directly challenge the long-standing assumption that forests and farming are locked in competition for land. Instead, the evidence makes clear that the real conflict is between short-term agricultural expansion and the long-term viability of the very systems that produce food.

A new report led by the FAO, launched at the conference, underscores that climate-resilient farming depends on the ecological functions performed by forests and trees, from cooling land surfaces and sustaining rainfall to regulating water flows, reducing soil loss and protecting rural workers from life-threatening heat. The findings directly challenge the long-standing assumption that forests and farming are locked in competition for land. Instead, the evidence makes clear that the real conflict is between short-term agricultural expansion and the long-term viability of the very systems that produce food.

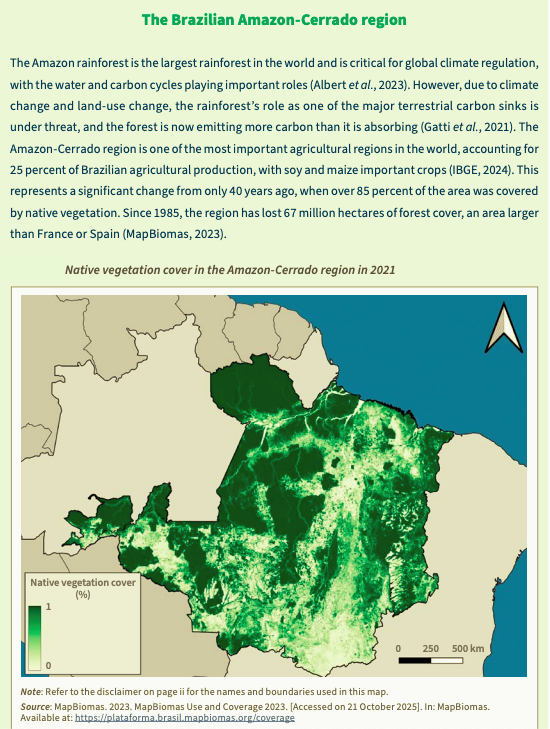

The report, Climate And Ecosystem Service Benefits Of Forests And Trees For Agriculture, developed by the FAO, the Stockholm Environment Institute (SEI), Conservation International (CI) and The Nature Conservancy (TNC), draws on global datasets to show that forests moderate temperatures, generate atmospheric moisture, stabilise hydrological cycles and support biodiversity that underpins crop productivity. It cites Brazilian studies demonstrating that converting tropical forests to farmland reduces evapotranspiration by up to 30 per cent, raising local temperatures and depressing rainfall essential to crops. It also reveals that agriculture in 155 countries depends on forests — often across borders — for as much as 40 per cent of annual rainfall. Deforestation disrupts these continental-scale moisture flows, weakening agricultural resilience far beyond the site of forest loss.

This climate destabilisation has immediate human consequences. Rising temperatures in deforested tropical regions have contributed to an estimated 28,000 heat-related deaths every year between 2001 and 2020. Between 2003 and 2018, workers in these hotter landscapes lost as many as 2.8 million safe working hours annually. Fields without shade expose farm labourers to dangerous levels of heat stress, affecting health and productivity and sometimes pushing adaptation limits. The report shows that restoring even half of the world’s lost tropical forests could cool land surfaces by about 1 degree Celsius, making entire agricultural regions more habitable for both crops and workers.

Forests also function as hydrological regulators. Their roots draw water into soils, their canopies slow rainfall impact, and their presence reduces runoff and erosion while allowing gradual moisture release during dry spells. These processes become increasingly vital as climate change drives more erratic precipitation patterns. In forested catchments, groundwater recharge is stable, irrigation reliability improves, and farms downstream benefit from moderated drought and flood risks. When forests disappear, these services collapse. For countries reliant on rainfed agriculture — nearly 90 to 95 per cent of farmland in parts of South America and sub-Saharan Africa — the implications are stark.

Despite these well-documented benefits, most national development plans still treat agriculture and forests as separate spheres. Policies frequently incentivise agricultural expansion into forest areas while failing to support practices that keep trees within farmland. The FAO-led report highlights that such siloed governance structures are outdated and increasingly costly. It argues that agricultural ministries, forestry agencies, water authorities, labour departments and public health systems all have stakes in forest stewardship, and the absence of coordinated frameworks weakens every sector. Integrating forest conservation into agricultural development agendas, therefore, becomes not just desirable but essential for national climate adaptation, food security and rural welfare.

Achieving such integration requires redesigning incentives. Many current subsidy regimes — whether covering fertilisers, credit, irrigation infrastructure or input support — encourage forest clearing by rewarding area expansion rather than productivity gains through ecological stability. Redirecting even a fraction of these subsidies to promote agroforestry, riparian buffers, forest patches and climate-resilient cropping systems would align agricultural support with ecosystem preservation. Agricultural extension systems would need to be reoriented to provide technical guidance on tree management within farms, including species selection, planting design, soil compatibility and moisture retention techniques. Incorporating tree-cover targets into agricultural district plans would ensure that productivity and ecological outcomes are monitored together rather than in isolation.

Institutional structures would also require transformation. Forest–agriculture task forces involving the Ministry of Agriculture, the Ministry of Environment and Forests, the Ministry of Water Resources, the Ministry of Finance, national planning bodies and the Ministry of Labour could guide integrated land-use planning at watershed and landscape scales. Such bodies would identify zones where forest restoration maximises agricultural benefits, such as headwaters, recharge zones, wind corridors and heat-vulnerable plains. They would also craft joint policies that prevent contradictions between agricultural incentives and forest regulations. Over time, coordinated frameworks would help countries embed non-carbon forest benefits — such as evapotranspiration contributions, cooling effects and hydrological regulation — into Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and National Adaptation Plans (NAPs).

Financing this integration calls for both traditional and innovative instruments. Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) schemes can compensate communities for maintaining forest cover that supports rainfall and water availability downstream. Jurisdictional programmes under the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation mechanism (REDD+) can reward regions that reduce deforestation while improving agricultural outcomes. Biodiversity bonds, green bonds and emerging mechanisms such as the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF) open pathways for channelling climate finance into mixed forest–agriculture landscapes. For such investments to be credible, countries need monitoring systems that quantify land-surface temperature trends, tree cover on farms, moisture recycling metrics and labour heat-stress indicators. Linking finance to measurable outcomes also reduces the risk of elite capture and increases transparency.

The social dimension is just as critical. Forest-dependent agricultural landscapes often overlap with Indigenous territories and smallholder farms. Securing land tenure provides these communities the confidence to invest in agroforestry, restoration and sustainable land management. Co-designed solutions — where communities shape monitoring systems, benefit-sharing agreements and land-use rules — reduce conflict and encourage long-term stewardship. In areas where conservation limits land-use options, social protection measures such as transition grants, alternative livelihood support, and access to low-carbon household energy sources help ensure that conservation does not disproportionately burden vulnerable households.

Managing integration also means recognising trade-offs. Trees can compete with crops for light or nutrients, harbour pests or reduce water yields in specific contexts. The FAO-led report notes that forest–agriculture interactions vary dramatically with local ecology, species choice and spatial configuration. Policies must therefore encourage context-specific design rather than one-size-fits-all solutions. Landscape assessments that combine biophysical modelling with socioeconomic mapping can identify which combinations of tree cover, crop type, and landscape design maximise benefits and minimise harms. Adaptive management — testing solutions in pilot landscapes before scaling them — helps refine interventions and avoid costly mistakes.

A crucial dimension of integration lies in protecting rural workers as temperatures rise. Forest conservation reduces heat stress by creating cooler microclimates across farms. National labour guidelines can incorporate shade requirements, flexible working hours and heat-protection protocols shaped around the ecological functions of trees. Rural health systems can track heat-related illnesses, while agricultural ministries can support farmers to integrate shade trees as part of productivity strategies rather than as cosmetic or peripheral additions.

The monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) systems needed to embed these non-carbon benefits into climate and agricultural planning are becoming clearer. National statistics offices and environmental agencies can combine satellite data and field measurements to track tree cover on farmland, changes in evapotranspiration rates, localised cooling effects and moisture recycling patterns. Water ministries can quantify how forest cover influences rainfall reliability across river basins. Labour ministries can measure safe working hours using the Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) index. Regular reporting — annually for tree cover and land-surface temperature changes, biennially for water and labour indicators and every five years for integrated agricultural productivity outcomes — would make forest–agriculture synergies visible in national development planning.

If these shifts seem expensive, the alternative is far costlier. Without forests, agricultural systems face cascading failures — unstable water supplies, declining yields, rising pest pressure, degraded soils and increasingly dangerous working conditions. Integrating forest conservation into agricultural development is therefore a pragmatic strategy for safeguarding national food systems and rural livelihoods in a warming world.

As COP30 negotiators in Belém weigh the global climate agenda, the evidence presented here places forests firmly within the agricultural policy domain. Forests are not ecological luxuries but agricultural infrastructure, regulating temperature, rainfall and hydrology in ways no engineered system can replicate at scale. By realigning incentives, strengthening cross-sector governance, securing community rights, improving data systems and designing contextually appropriate landscape solutions, countries can build agrifood systems that endure and thrive. The science shows that where forests fall, farms eventually falter. Where forests flourish, agriculture finds its most reliable ally.

– global bihari bureau