An online JD(U) poster after the Bihar election verdict.

Women, Youth, and NDA: The Formula That Won Bihar

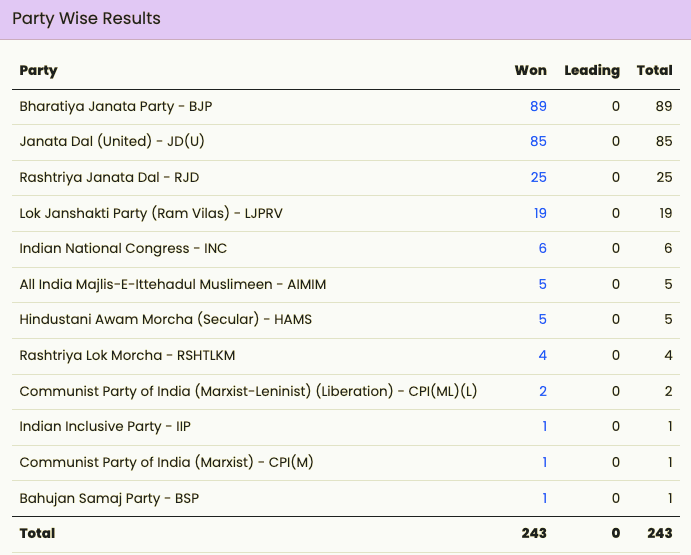

Patna/New Delhi: The verdict of the 2025 Bihar Legislative Assembly election is unequivocal. The National Democratic Alliance (NDA), led in the state by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its partner the Janata Dal (United) (JD(U)), has secured a sweeping mandate, transforming what might have been expected as a hard‑fought contest into a near‑landslide. The alliance has won 202 seats in the 243‑member assembly, delivering a decisive message to both the electorate and the opposition. For the rival Mahagathbandhan, led by the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and including the Indian National Congress (INC) among others, this translates into a dramatic reversal of political fortunes, with the coalition winning 35 seats (RJD 25, INC 6).

The new Chief Minister (likely Nitish Kumar, given JD(U)’s strong showing and his incumbency) and cabinet are anticipated to be sworn in on November 17, 2025, at Raj Bhavan in Patna.

The NDA’s total, which includes the BJP’s 89-seat surge and JD(U)’s 85 seats, reflects far more than a simple re‑election of incumbents. It represents a consolidation of electoral power, a signal of governance continuity, and a demonstration of coalition discipline.

Meanwhile, the Mahagathbandhan has found itself not merely defeated but significantly diminished: its core social-coalition strategy visibly faltered, its messaging failed to broaden beyond established vote-banks, and its leadership was unable to convert hope into credible electoral performance.

For national figures such as Rahul Gandhi, the implications are stark. As leader of the Congress, his campaign in Bihar—and his narrative around electoral malpractice—yielded one of the party’s worst performances in the state. With only a handful of seats won, Congress remains largely marginal, highlighting the persistent gap between national rhetoric and the state-level political realities. For Rahul Gandhi, this outcome is a reminder that prominence on the national stage does not automatically translate into state-level influence.

The political future of the RJD and the extended Yadav family is similarly unsettled. Tejashwi Yadav, though comfortably re-elected from Raghopur, could not reverse the party’s overall decline. His elder brother, Tej Pratap Yadav, also failed to make a significant impact beyond his contested seat. The once reliable Yadav-Muslim axis, which underpinned the RJD’s ascendancy, proved insufficient to secure victory. The coalition’s inability to expand into Other Backward Classes (OBCs) and Mahadalits underscores the erosion of its social engineering strategy and points to an urgent need for political recalibration.

At the centre of the verdict stands Nitish Kumar. His role goes beyond being a partner in the NDA; he has once again demonstrated political instinct and a governance narrative that resonates with voters. Over decades, he has shifted alliances, adapted to changing caste dynamics, and sustained his relevance. This election reinforces his ability to knit a winning coalition, manage alliance seat-sharing with precision, and project a governance-focused narrative that voters trust. His victory should be regarded as a reaffirmation of his statesmanship, marking a notable chapter in Bihar’s political history.

Several factors contributed to the NDA’s commanding performance. High voter turnout signalled enthusiasm and mobilisation that favoured parties with strong organisational infrastructure. The alliance’s cohesion allowed for disciplined campaigning, coordinated messaging, and effective outreach across constituencies, particularly in Dalit-dominated seats. Additionally, welfare measures targeted at women, including direct benefit transfers and other social programs, appear to have mobilised female voters significantly, tipping close races in favour of the NDA. In contrast, the Mahagathbandhan struggled to convert its presumed base into a winning coalition, over-relying on traditional Yadav-Muslim support while failing to reach other OBC groups, Mahadalits, and urban voters.

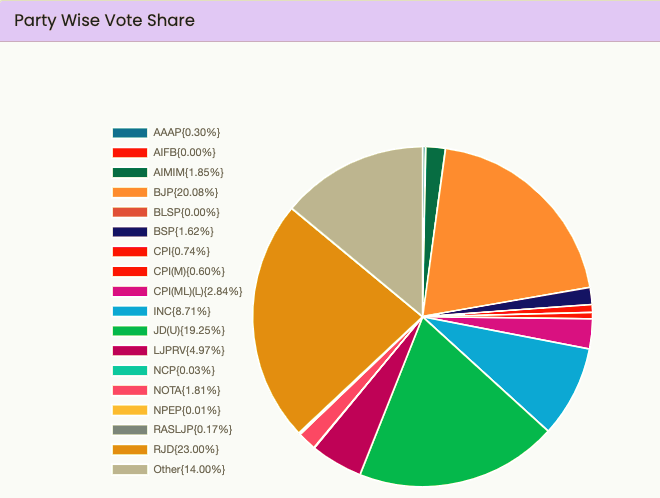

According to official data from the Election Commission of India, the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) secured the highest vote share of the major parties in the 2025 Bihar Legislative Assembly elections at 23.00 %, while the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) registered around 20.08 %. The Janata Dal (United) (JD(U)) stood at approximately 19.25 %.

Despite topping the vote share, the RJD’s conversion of votes into seats proved inefficient compared with the BJP‑JD(U) alliance, highlighting the critical importance of effective vote‑to‑seat translation under the first‑past‑the‑post system. This discrepancy underscores the NDA’s strategic advantage in consolidating constituencies and converting targeted outreach—including rural, female, and Mahadalit mobilisation—into tangible legislative gains. The figures also reinforce the observation that numerical dominance alone is insufficient without disciplined ground-level execution, alliance coherence, and attention to localised caste and community dynamics.

Caste arithmetic played a central role in the electoral outcome. While the RJD has historically relied on Yadav-Muslim coalitions, the NDA expanded its appeal to non-Yadav OBCs, Mahadalits, and economically marginalised voters, complemented by strong female and youth turnout. The realignment of these blocs diluted the RJD’s numerical advantage and illustrated that successful caste-based strategies must evolve with demographic shifts and changing voter priorities. The Muslim vote, once assumed to be monolithic in favour of the RJD, splintered in several regions, reflecting a more discerning and issue-focused electorate.

Women’s participation was pivotal. The NDA’s emphasis on welfare schemes, financial empowerment, and security resonated strongly with female voters, demonstrating that targeted outreach to women can decisively influence results. Their votes were not only a matter of turnout but actively shaped outcomes in constituencies that were otherwise tightly contested.

The pre-election Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls drew controversy. Its “acceptance” merits nuance on migrant turnout dips in Seemanchal. Opposition parties claimed that it disproportionately affected migrant labourers, economically disadvantaged groups, and religious minorities, raising fears of disenfranchisement. However, in practice, these claims did not manifest in reduced voter turnout or visible protest, suggesting that the electorate accepted the process as largely legitimate or prioritised governance and development over procedural grievances. The SIR controversy, therefore, had minimal impact on the final verdict.

The performance of the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM), winning a few seats in Muslim-concentrated regions, highlighted fractures within the traditional Muslim vote-bank of the RJD. While numerically limited, AIMIM’s success underscored that communal vote assumptions can no longer guarantee outcomes and that local issues and leadership choices increasingly matter.

In what was one of Bihar’s most closely watched political experiments, Prashant Kishor’s Jan Suraaj Party (JSP) failed to secure a single seat despite contesting almost all constituencies. The party’s narrative of governance reform and change resonated in urban and digital spheres, but the lack of a ground-level structure, weak booth presence, and overreliance on professional candidates over local stalwarts hindered its performance. This outcome underscores the continued difficulty of establishing a third front in Bihar, where politics remain deeply localised, caste and community networks dominate, and sustained organisational presence is essential. The failure of the JSP also signals the challenge of transforming strategic vision into electoral results in a competitive, alliance-driven landscape.

Turnout data for the 2025 election reflects one of the most striking shifts in Bihar’s electoral landscape. The official figures show that the state recorded a voter turnout of 66.91 %, the highest since the first assembly elections in 1951, and within that figure, women cast their ballots in significantly greater proportion than men: 71.6 % of female electors compared to 62.8 % of male electors. The gap widened further across the two phases of polling: in Phase I, women turned out at about 69.04 % while men were at 61.56 %, and in Phase II women surged to 74.03 % compared with 64.1 % for men. This gender differential has significant implications for the result: the alliance that managed to convert high female participation into votes gained the decisive edge. In the case of the NDA, the mobilisation of women voters appears to have been a critical element in close constituencies and arguably helped widen the margin of victory beyond traditional strongholds.

At the same time, while constituency-level data with urban-rural splits and full vote shares by party are still emerging, early trends point to meaningful shifts in regional patterns and caste-based arithmetic. Reserved seats for Scheduled Castes (SC) are early indicators: the NDA was leading in 35 out of the 38 SC-reserved constituencies, while the Mahagathbandhan held 3. What this suggests is that the NDA’s appeal extended beyond its core OBC and upper-caste base into Mahadalit, non-Yadav OBC, and Dalit segments that have traditionally been harder to mobilise. At the same time, regions with large migrant populations and rural hinterlands—especially in Seemanchal, where women’s turnout in some seats fell as migrant shifts grew—hint at the complex interplay of migration, voter registration revisions, and local alliances. While the full urban-rural breakdown remains unavailable, the available signals underscore that even in rural constituencies with strong caste identities, the vote is beginning to incorporate gender, welfare outreach, and alliance discipline as critical variables beyond the old arithmetic.

In the regional breakdown of the state, the performance across distinct geographic clusters reinforces the broader trends. In the Seemanchal belt, comprising districts such as Araria, Kishanganj, and Purnea, the expectation had been that the Opposition alliance, anchored by the Yadav–Muslim formula, would dominate. Instead, the NDA captured significant ground even in this region, while the AIMIM registered gains, leading in several seats and thereby eroding the monopoly of the Mahagathbandhan over Muslim-concentrated constituencies. In the Magadh division, covering districts such as Gaya, Jehanabad, Nawada, and Arwal, Dalit-dominated seats and divisions of non-Yadav OBCs fell largely to the BJP and its allies, aided by the fragmentation of sub-caste loyalties and the relative weakness of the opposition’s local infrastructure.

Urban-rural dynamics in the 2025 Bihar election added important layers to the outcome. While full breakdowns of votes by party in every constituency remain pending, available data indicate that rural turnout and mobilisation were significantly stronger than in many urban pockets. This implies that the NDA could capitalise on its rural organisational strength and welfare-scheme outreach more effectively than its opponents. Urban areas, especially in localities with strong middle-class and migrant populations, remained more volatile and less consistently mobilised, reducing their impact in the larger tally.

Selected constituencies illustrate micro-level shifts. In Raghopur, Tejashwi Yadav’s narrower victory margin reflected weakening support from non-Yadav OBCs and Mahadalits. In Kishanganj, the NDA’s improved vote share and AIMIM’s presence highlighted the erosion of RJD’s previously solid Muslim base. In Magadh and Tirhut divisions, rural mobilisation and women-focused outreach enabled NDA victories in seats previously considered marginal. These patterns underscore that Bihar’s electorate is now influenced by governance, candidate credibility, and demographic outreach rather than solely historical caste loyalties.

Phase-wise analysis shows that Phase II constituencies, covering central and southern districts, recorded the highest voter participation, particularly among women and youth. NDA strategies, including welfare announcements and digital outreach timed with Phase II polling, amplified turnout and converted it into an electoral advantage. The SIR controversy had a limited effect, as increased mobilisation offset any potential disenfranchisement.

Youth participation, urban-rural splits, small-party performance, and comparative vote-share analysis collectively explain the NDA’s consolidation. The BJP-JD(U) alliance effectively mobilised rural, female, and youth voters, penetrated Mahagathbandhan strongholds, and leveraged local candidate credibility. Meanwhile, the Mahagathbandhan’s reliance on historical Yadav-Muslim alliances, limited outreach to women and youth, and weak organisational structure restricted its gains. Smaller parties like Lok Janshakti Party (Ram Vilas) complemented NDA consolidation, while AIMIM fragmented the opposition, and Jan Suraaj Party’s absence of local presence underscored the dominance of two-block politics.

The cumulative evidence presents a comprehensive picture: the 2025 Bihar election demonstrates how organisational discipline, alliance cohesion, demographic targeting, and strategic candidate selection decisively shape outcomes. Nitish Kumar’s leadership, NDA alliance execution, caste arithmetic recalibration, and mobilisation of women and youth collectively produced a historic mandate. For the Mahagathbandhan, the verdict signals the urgent need for strategic re-evaluation. Bihar’s electorate has clearly signalled that governance performance, inclusive outreach, and local credibility now outweigh legacy loyalties.

– global bihari bureau