![]() By Deepak Parvatiyar*

By Deepak Parvatiyar*

Freebies on Empty: Bihar’s ₹70K Cr Black Hole

Patna: Bihar’s election season has always been noisy, but this time the loudest sound is arithmetic. The ruling National Democratic Alliance’s (NDA) Sankalp Patra 2025, released on October 31, promises over one crore government jobs and employment opportunities through a statewide skill census and mega training centres in every district, while pledging to transform one crore women into Lakhpati Didis with self-employment loans up to ₹2 lakh under the Chief Minister’s Women Employment Scheme and guaranteeing 125 units of free electricity. The opposition Mahagathbandhan’s Tejashwi Pran, unveiled on October 28, 2025, offers a law within 20 days for one government job per family across 2.5 crore households, ₹2,500 monthly transfers to 22.5 lakh women under the Mai-Behan Yojana, 200 units free electricity for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Old Pension Scheme revival in the first cabinet, and full farm loan waivers estimated at ₹50,000–75,000 crore.

With first-phase polling opening in seventy-two hours, Bihar’s rival alliances have turned the campaign into a promise auction. Both manifestos read like blueprints for prosperity; the state’s own ledgers tell another story — of receipts that can’t keep up, audits that warn of missing vouchers, and welfare schemes that stall halfway between allocation and delivery. Neither the NDA nor the Mahagathbandhan names funding sources beyond vague nods to central aid and private partnerships.

The government’s 2025–26 Budget Speech, tabled by Deputy Chief Minister Samrat Choudhary, projects a total outlay of ₹3.17 lakh crore, a 13.7 per cent rise over the previous year. Forty-four per cent of that — roughly ₹1.4 lakh crore — is pre-committed to salaries, pensions, and interest payments. Bihar’s own tax revenue stands at just over ₹1.2 lakh crore; the remainder depends on central transfers. The state’s liabilities now exceed ₹3.3 lakh crore, about 28 per cent of its gross state domestic product. The CAG’s State Finances Audit Report 2023–24 (Report No. 1 of 2025) records a fiscal deficit of 3.23 per cent and warns that “the growing revenue expenditure on committed liabilities reduces the fiscal space for developmental spending.” The report calls this “a structural constraint on future policy flexibility.”

That constraint has been deepening for years. In successive reports since 2020-21, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG) has tracked the same fault lines. The CAG’s State Finances Audit Report No. 1 of 2025, tabled in July 2025, recorded 49,649 pending utilisation certificates worth ₹70,877.61 crore, including ₹14,452 crore pre-2017 legacy, and 22,130 unvouchered Abstract Contingent bills totalling ₹9,206 crore. It also flagged ₹144 crore unpaid interest on deposits, ₹53 crore undisclosed off-budget liabilities, and utilisation at 79.92 per cent with ₹65,512 crore surrendered. The CAG warned that the absence of utilisation certificates provides no assurance that funds reached beneficiaries and carries a high risk of embezzlement, misappropriation, and diversion.

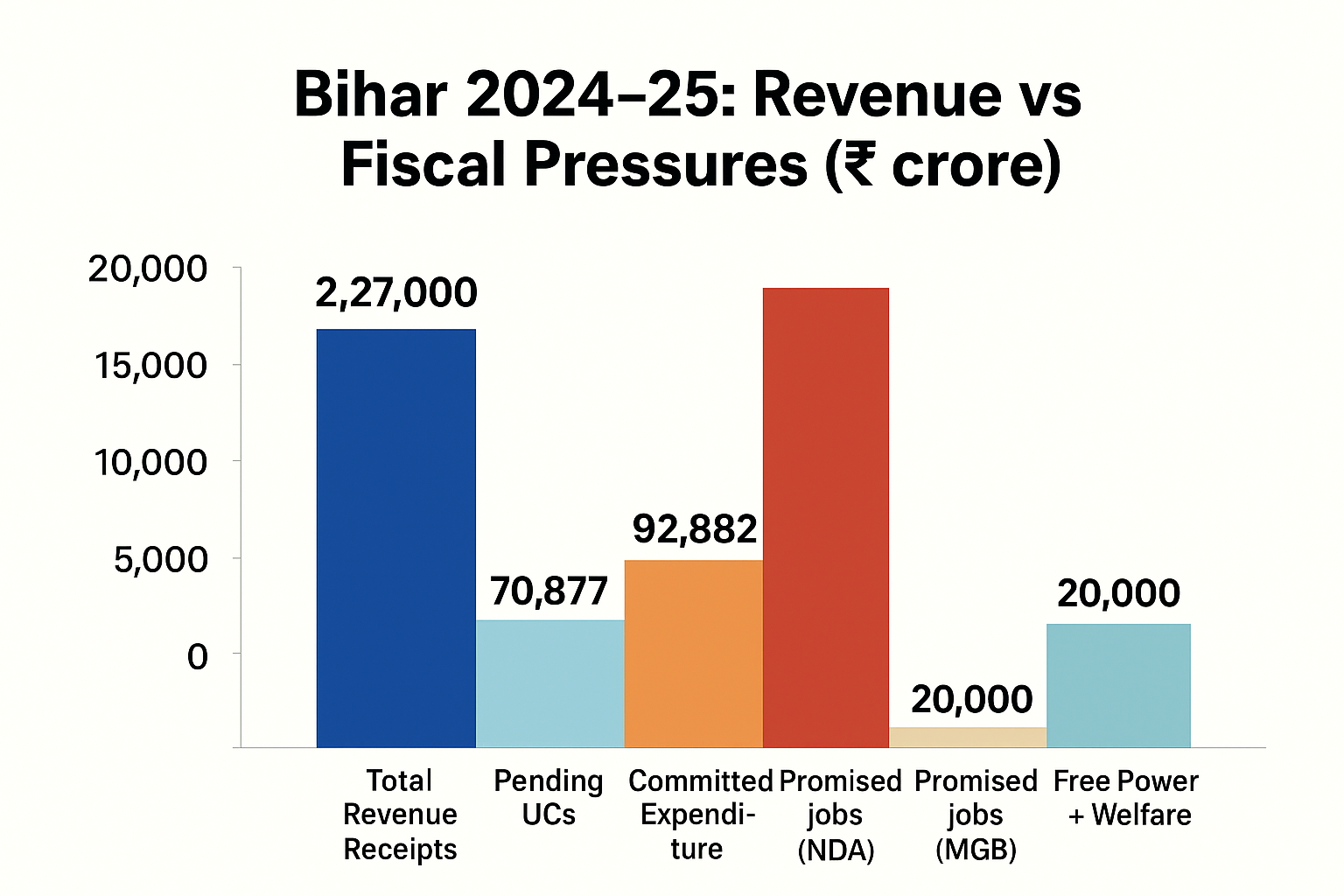

In simpler terms, Bihar has spent money it has yet to explain. This backdrop turns the manifestos’ job bonanzas into implausible arithmetic. The NDA’s promise of one crore jobs assumes a capacity to fund, recruit, and manage an employment drive larger than the total number of sanctioned state positions today. Even the education and labour departments combined employ barely five lakh people. If each new job were to cost an average of ₹2 lakh per year in salary and allowances, the bill would equal the state’s entire revenue pool. The Mahagathbandhan’s commitment to ten lakh government jobs and a family-wise employment guarantee would, on conservative calculation, add ₹20,000–25,000 crore a year to the wage bill. The 2025–26 Budget allocates ₹40,194 crore for salaries. The CAG’s 2021–22 audit already flagged “persistent shortfalls in the filling of sanctioned posts” as a cause of under-performance in education and health. Promises of sudden mass hiring run straight into that historical bottleneck.

Welfare pledges compound the strain. The NDA’s 125 units free electricity cost ₹5,000 crore annually, atop ₹13,483 crore existing subsidies, its ₹5 lakh health cover another ₹10,000 crore, and Lakhpati Didi loans ₹12,000 crore in interest subsidies, totalling ₹27,000 crore or one-eighth of revenue. The Mahagathbandhan’s 200 units of free electricity cost ₹15,000 crore, ₹25 lakh Central Government Health Schem (CGHS)-style insurance ₹20,000 crore, and Mai-Behan transfers ₹42,000 crore, summing to ₹77,000 crore yearly. Both ignore 38 per cent transmission losses and ₹97 crore central grants lost to non-compliance noted in the 2021–22 power audit.

Infrastructure ambitions dwarf capacity. The NDA’s seven expressways, 3,600 km of rail modernisation, four metro cities, and three international airports require capital outlay far beyond ₹64,984 crore when public works utilisation averages 75–80 per cent, leaving ₹50,000 crore unspent annually, with 15 of 44 Smart City projects unapproved and ₹50–100 crore diverted per the 2021–22 compliance audit. The Mahagathbandhan’s IT parks and coaching revival lack any cost estimate. Agriculture promises clash with reality: the NDA’s ₹1 lakh crore infra and panchayat-level MSP versus ₹25,000 crore allocation with ₹16,193 crore UC backlog in rural development, cold storages uncommissioned for missing power connections; the Mahagathbandhan’s loan waivers and ₹10,000 PM-KISAN hike would consume two years’ rural vote.

The deeper issue is not simply money but execution. The CAG’s 2023–24 report records that major departments utilised between 75 and 80 per cent of their annual budget provisions on average, leaving roughly ₹50,000 crore unspent each year. The Rural Works Department alone accounted for 22 per cent of unutilised funds. In audit after audit, the same words recur: “inadequate planning,” “delayed release,” “non-submission of completion certificates.” The pattern predates any one government; it defines Bihar’s bureaucracy itself. The Mahagathbandhan’s offer of a ₹50,000 crore farm-loan waiver, for instance, would rely on the same machinery that has not yet reconciled ₹16,000 crore of rural-development expenditure.

Health, which both alliances claim as a centrepiece, has been repeatedly red-flagged. The CAG’s performance audit of health infrastructure, tabled in 2024, found that 49 per cent of doctor posts were vacant across district hospitals and primary centres, and shortages of essential drugs ranged from 21 to 83 per cent. It also documented overpricing of ₹2.86 crore in medicine procurement by the Bihar Medical Services Corporation Limited. Despite these findings, the NDA’s manifesto promises new “district medicities” and expanded insurance, while the Mahagathbandhan proposes ₹25 lakh medical cover for every family. The audit data imply that the challenge is not new schemes but basic functionality: facilities without staff, and procurement without control.

Education tells the same story. The CAG’s audits between 2021 and 2023 show that 1.5 lakh sanctioned teacher posts remain vacant, and that school infrastructure projects worth hundreds of crores were delayed or left incomplete. In 2023–24, the Education Department surrendered ₹1,234 crore of unspent funds. Yet both manifestos promise free education “from KG to PG” and large-scale recruitment of teachers. The contrast is arithmetical: Bihar already allocates nearly a fifth of its budget — ₹60,954 crore this year — to education and skills. Spending more is not the problem; spending effectively is.

The CAG’s findings on welfare spending are equally stark. The 2022–23 report recorded ₹52 crore in grants for construction workers left undistributed for more than two years because the welfare board meant to disburse them had not been constituted. The 2023–24 audit observed that “schemes remained incomplete despite full release of funds,” listing examples from the Health and Rural Development departments. Bihar’s welfare promises — cash to women, stipends to youth, subsidies to entrepreneurs — all depend on a delivery apparatus with this record.

When confronted with those audit findings in the Assembly, ministers have cited “legacy issues” and blamed delays on overlapping schemes. Deputy Chief Minister Samrat Choudhary, in the August 2025 assembly debates, blamed 60 per cent of ₹70,877 crore UC pendency on 2015–20 Grand Alliance tenures and claimed 10 per cent clearance via monthly monitoring ordered by Chief Minister Nitish Kumar, yet the Public Accounts Committee held zero sittings in 2023–24, leaving 385 of 388 audit paragraphs undiscussed. The CAG’s July 2025 follow-up reiterated glaring deficiencies, noting only a “marginal improvement” in reconciliation. Tejashwi Yadav of the opposition has used the same reports to accuse the government of “₹80,000 crore of scams” in unverified spending, branding the NDA document a “sorry patra.”

The blame-trading is predictable; the documents neither exonerate nor confirm such charges. They describe weaknesses in accounting and control that have persisted through multiple administrations, coalition or otherwise. Until the audit backlog is cleared, revenue base expanded, and execution systems reformed, every manifesto guarantee remains a post-dated cheque on a failing treasury.

Economists who work on state budgets read those weaknesses as structural, not episodic. PRS Legislative Research points out that nearly seventy per cent of Bihar’s revenue comes from the Centre. That dependence limits the state’s flexibility: when central transfers slow, development spending must shrink unless borrowing rises. The Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act caps the deficit at 3 per cent of GSDP; Bihar has hovered just above that limit. New permanent entitlements — salaries, pensions, subsidies — would push it higher. The CAG’s 2023–24 report warns that “continued revenue deficits despite rising grants point to fiscal stress.”

The political rhetoric moves in the opposite direction. Both manifestos present spending as stimulus and entitlements as empowerment. Neither engages with the arithmetic of constrained revenue and chronic under-utilisation. The numbers in the state’s own documents are less dramatic but more revealing. In 2025–26, developmental expenditure is ₹1.55 lakh crore — roughly half the total outlay — but almost all of it is absorbed by ongoing schemes. Capital expenditure growth, the measure of new assets created, is budgeted to rise only marginally. Bihar’s infrastructure deficit, estimated by the Economic Survey at nearly ₹2 lakh crore, cannot be closed by borrowing alone.

The CAG’s social-sector audits make the cost of that gap visible in human terms. Maternal mortality remains twice the national target. Health centres operate without staff. Classrooms exist without teachers. Water-supply projects miss deadlines because of unspent funds. The CAG’s phrase for this, repeated in report after report, is “inefficiency in utilisation.” Each unutilised rupee is an unfinished clinic, an unbuilt road, an unpaid worker. Yet the manifestos speak in the future tense, as if the state’s administrative present were already fixed.

None of this means ambition is unwarranted; Bihar’s electorate expects transformation. But transformation has to be audited too. To make the promises in these manifestos credible would require first reconciling those ₹70,877 crore in unverified expenditures, closing the ₹9,205 crore of contingent bills, and ensuring departments certify completion of old projects before announcing new ones. Without that, new schemes will land on old backlogs.

The auditor’s reports are not partisan tracts; they are bureaucratic documents written in neutral prose. Their warnings, though, amount to a political indictment of a system that writes promises faster than it files vouchers. “Internal controls remain inadequate,” one report concludes. Another observes that “budgetary assumptions are not supported by realistic revenue estimates.” Taken together, they describe a government — any government — whose words outpace its ledgers.

As the campaign noise builds across Darbhanga and Gaya, the balance sheet sits quietly in Patna’s Finance Department, rows of figures showing receipts, outlays, and pending accounts. Between those pages and the manifestos lies the gap Bihar must close. The numbers do not care which coalition wins; they will still have to be reconciled. The state’s audit trail — the missing utilisation certificates, the idle funds, the unfilled posts — is not a partisan narrative but a ledger of unfinished work.

Bihar’s real election promise is not a crore jobs or a crore entrepreneurs. It is whether a new government, any government, can clear the old accounts, spend what it allocates, and account for what it spends. Until that happens, manifestos will remain glossy pamphlets pinned to a filing cabinet marked pending verification.

In the end, it is worth pointing out that the Election Commission of India’s Model Code of Conduct (MCC), Part VIII: “Guidelines on Election Manifestos”, complies with the Supreme Court’s 2013 judgment (S. Subramaniam Balaji v. State of Tamil Nadu & Others, Civil Appeal No. 5130 of 2013). The Commission clearly says that while a manifesto “shall reflect the rationale for the promises made” and “the ways and means to meet the financial requirements of such promises”, it should also explain the broad principles of resource mobilisation to meet those commitments. In 2022, the ECI strengthened these rules by directing that political parties must file a standardised disclosure form with details on the financial implications of each promise; how resources will be generated to fulfil them; and the likely impact on the fiscal sustainability of the state or the Centre.

Have the political parties in Bihar submitted these disclosures to the Commission and publicised them for transparency? At the moment, there is no such confirmation on whether the required disclosure under the 2022 directive has been submitted or made public in the Bihar case. Will the ECI clarify?

*Senior journalist