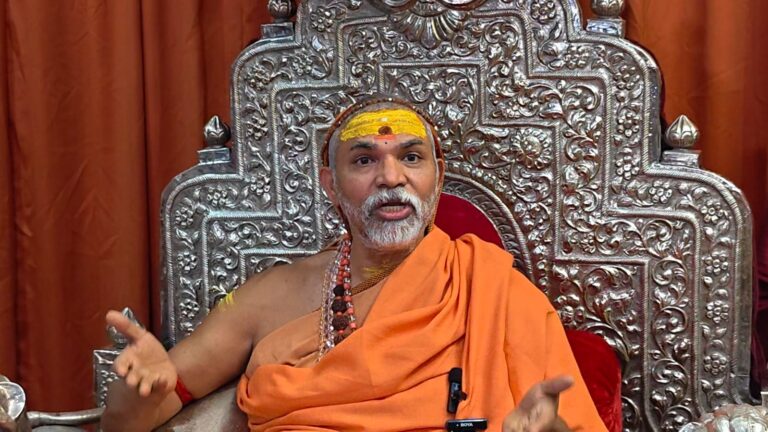

Photo by Rahul Laxman Patil

By Nava Thakuria*

By Nava Thakuria*

BNP Takes Power as India Weighs Regional Risks

Bangladesh’s New BNP Regime Signals Reset with India

Bangladesh has constituted a new government under the leadership of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) following a largely fair and peaceful national election held on 12 February 2026, raising expectations across eastern India for political stability and economic progress in the neighbouring country of more than 170 million people. The eastern Indian region, which almost surrounds Bangladesh except for narrow stretches touching Myanmar and the Bay of Bengal, is watching developments in Dhaka with cautious optimism. Many hope that the new dispensation will usher in a phase of stability and development for the South Asian nation, but deep-rooted concerns remain, particularly in the northeastern states such as Assam, where the impact of events in Bangladesh is felt most directly. For years, Bangladesh has remained a source of anxiety for Assam and adjoining states, primarily for two reasons: the unabated influx of migrants and persistent regional security concerns that affect millions of indigenous families in their homeland.

The geographical and political sensitivity of the region is frequently highlighted by sections of motivated opinion within Bangladesh, which point to India’s vulnerability around the Siliguri corridor, popularly described as the “chicken’s neck”, the narrow land bridge that connects the northeastern states to the rest of India. Some of these elements go beyond strategic commentary and openly fantasise about incorporating large parts of eastern India to establish what they describe as a “Greater Banglasthan”. They argue that an affluent and powerful nation must possess access to the sea, a fertile valley with abundant water bodies and a range of mountains, and in this vision, they even extend their imagination to parts of Bhutan and Tibet. Parallel to this expansionist rhetoric is the belief held by some that Bangladesh, which nurtures a single linguistic identity in Bengali, should also evolve into a mono-religious state centred on Islam. Though such views are not representative of mainstream opinion, they contribute to a climate of unease in India’s northeast, where historical memories of displacement and demographic change remain sensitive political issues.

Against this backdrop, the February 2026 election assumed significance not only for Bangladesh but also for its neighbours. The poll, held in an unusually festive atmosphere not commonly witnessed in the country’s electoral history, recorded a voter turnout of around 60 per cent. The BNP secured a sweeping victory by winning 212 seats in the 300-member Parliament, with another 50 women members to be added to the Jatiya Sangsad under the constitutional provision. Sixty-year-old Tarique Rahman, son of former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia and former President Ziaur Rahman, led the party through the electoral contest without resorting to provocative anti-India rhetoric, a tool that has often been used in Bangladeshi politics to gain instant popularity among sections of the electorate. Even after taking the oath as Prime Minister, Rahman maintained a measured and calm tone, emphasising the importance of holistic relations with neighbouring countries, including India.

The rise in anti-India speechifying in Bangladesh in recent years gathered momentum after the ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina took shelter in New Delhi, where she, along with thousands of Awami League leaders, has continued to seek political asylum since her sudden departure from Dhaka on 5 August 2024. The interim government formed under the leadership of Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus repeatedly demanded Hasina’s extradition, citing a death sentence pronounced by a Bangladeshi tribunal. These requests did not elicit any positive response from India. Rahman, however, avoided aggressive or emotional remarks against Hasina, who dismissed the 13th Jatiya Sansad as a farce. He confined himself to stating that her repatriation should be pursued through legal initiatives rather than political confrontation.

The election also drew attention because of its implications for religious minorities in Bangladesh, at a time when the country had attracted international media scrutiny over reports of atrocities against minority families in recent years. In a development seen as symbolically important, four non-Muslim candidates emerged victorious in the election, including two Hindus—Goyeshwar Chandra Roy and Nitai Roy Chowdhury—both nominated by the BNP and defeating Jamaat candidates in their constituencies. Two other winners from minority communities, Saching Pru and Dipen Dewan, were also BNP nominees. Prime Minister Rahman inducted Roy Chowdhury and Dewan into his cabinet. Hindus today constitute a dwindling population of around 13 million people, or about 8 per cent of Bangladesh’s total population, a sharp decline from more than 22 per cent at the time of Partition in 1947.

India moved swiftly to engage the new leadership in Dhaka. Prime Minister Narendra Modi promptly congratulated the BNP leadership on its decisive victory and became the first global leader to personally call Tarique Rahman. Modi expressed India’s interest in working with Bangladesh for the mutual benefit of both neighbours. The BNP leadership acknowledged the gesture and said Dhaka looked forward to engaging constructively with New Delhi to advance a multifaceted relationship guided by mutual respect, sensitivity to each other’s concerns and a shared commitment to peace, stability and prosperity in the region. Modi later congratulated Rahman on assuming office and invited him, along with his family members, to visit India at a mutually convenient time. Although he could not attend the swearing-in ceremony on 17 February, Modi deputed Lok Sabha Speaker Om Birla to represent India at the ceremony held at the southern courtyard of the Jatiya Sansad Bhawan in Dhaka.

Earlier, in his last televised address to the nation as chief adviser of the caretaker government, Yunus described the election as “not merely a transfer of power but the beginning of a new journey for Bangladesh’s democracy”. The globally acclaimed microcredit pioneer and social business promoter reminded citizens that the interim regime had begun its work from “minus, not even zero”, alleging that the poverty-stricken country had been left in ruins by the former ruler. The respected economics professor reiterated his belief that Bangladesh faced enormous opportunities through the expansion of regional cooperation with Nepal, Bhutan and India’s northeastern states. He concluded his address by appealing to Bangladeshis, along with political leaders, to uphold and strengthen the momentum for peace, progress and reforms with unwavering unity in the coming days.

Despite these hopeful signals, concerns for India in general and Assam in particular remain acute. Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami, an Islamist party that opposed the 1971 liberation movement by siding with West Pakistan, has emerged as the main opposition party in the Jatiya Sangsad for the first time in the country’s history. The Jamaat-led alliance of 11 parties won 77 seats, with the Shafiqur Rahman-led party itself securing victory in 68 constituencies, most of them in areas bordering West Bengal. The newly surfaced National Citizen Party, formed by students who orchestrated the July–August 2024 uprising that toppled Hasina’s government in Dhaka, joined hands with Jamaat in the electoral battle and won six seats.

Political observers believe that this configuration of forces represents a potential threat to the landlocked northeastern region of India and needs to be addressed efficiently by New Delhi through a careful recalibration of bilateral ties with its troubled neighbour. The rise of Jamaat as the principal opposition party has revived fears about the ideological direction of Bangladeshi politics and its implications for regional security, especially in states such as Assam that already struggle with demographic pressures and cross-border movements.

Senior BNP leader and now cabinet minister Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir, speaking to the BBC on February 16, expressed hope that Indo-Bangladesh relations would continue even as Dhaka pursued Hasina’s extradition from New Delhi. Alamgir said the BNP would persist in demanding her return and that the matter now lay in India’s court. He also insisted that every Bangladeshi national, irrespective of religion, should live happily and with dignity in Bangladesh. Responding to Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma’s recent pushback policy targeting alleged Bangladeshi migrants, Alamgir warned that such measures would negatively impact bilateral relations. He said the issue would be raised with New Delhi through appropriate diplomatic forums.

Once again, concerns for India, particularly Assam, resurfaced with the emergence of Jamaat-e-Islami as the main opposition force in Parliament. The party’s historical opposition to Bangladesh’s liberation struggle and its ideological orientation continue to alarm security analysts in India. Combined with the role of the National Citizen Party, born out of the student-led uprising that removed Hasina, the opposition landscape in Dhaka is now viewed as more complex and potentially volatile than in previous parliamentary terms.

Sections of Indian strategic opinion argue that the landlocked northeastern region, connected to the rest of the country by the narrow Siliguri corridor, faces a looming challenge that requires sustained diplomatic engagement and vigilance. They warn that narratives of territorial expansion, mono-religious identity and strategic leverage over India’s geography, even if held by fringe groups, cannot be ignored in a sensitive neighbourhood.

As Bangladesh embarks on a new political journey under Tarique Rahman, India confronts a dual reality: the promise of a democratically elected government that has signalled moderation and constructive engagement, and the persistence of ideological and security challenges rooted in history, geography and domestic politics within Bangladesh. Whether the BNP-led regime can translate its moderate tone into lasting cooperation with India, while managing internal pressures from powerful opposition forces, will shape the future of relations between the two neighbours and determine whether Dhaka can indeed turn friendlier to New Delhi in the years ahead.

*Senior journalist