Sediment Core Shows Strong Monsoon During Medieval Warm Phase

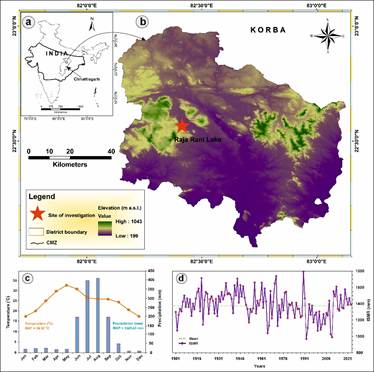

Lucknow: India’s monsoon history may have been far more intense than previously understood, according to new palaeoclimatic evidence extracted from ancient pollen preserved beneath a lake in central India. Scientists studying sediment cores from Raja Rani Lake in the Korba district of Chhattisgarh found clear indications of prolonged and unusually strong monsoon rainfall between approximately 1,060 and 1,725 Common Era (CE), suggesting a sustained warm and humid climatic phase during this period.

The findings emerged from a detailed investigation of vegetation dynamics and hydro-climatic variability in India’s Core Monsoon Zone (CMZ), a region where rainfall is primarily governed by the Indian Summer Monsoon and which contributes nearly 89 to 90 per cent of the country’s annual precipitation. Because this zone is particularly sensitive to fluctuations in monsoon behaviour, reconstructing its past climate is considered critical for understanding long-term monsoonal variability during the Late Holocene, also known as the Meghalayan Age.

The study was conducted by scientists from the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences, Lucknow, which is an autonomous institute under the Department of Science and Technology. The researchers focused on Raja Rani Lake, located at the heart of the CMZ, and extracted a 40-centimetre-long sediment core from the lake bed. These sediment layers preserved a continuous environmental archive spanning nearly 2,500 years.

Embedded within the mud layers were microscopic pollen grains released by plants that once grew around the lake. By identifying and counting these grains through palynology, the scientific study of pollen and spores, the researchers reconstructed past vegetation patterns and, by extension, the climatic conditions under which those plants thrived. A dominance of forest-dwelling plant species was interpreted as evidence of warm and humid conditions, while a higher proportion of grasses and herbs indicated comparatively drier phases.

The pollen record revealed that during the period corresponding to the Medieval Climate Anomaly, there was a marked dominance of moist and dry tropical deciduous forest species. This vegetation profile pointed to sustained strong monsoon rainfall and a warm, humid climate across central India. Significantly, the researchers found no evidence of prolonged dry phases within the CMZ during this interval, challenging earlier assumptions that parts of the region may have experienced contrasting arid conditions.

The strengthened monsoon was linked to the Medieval Climate Anomaly, a global warm phase dated roughly between 1,060 and 1,725 Common Era. The study suggested that the enhanced Indian Summer Monsoon during this time was driven by a combination of global and regional climatic factors. These included La Niña–like conditions, which are typically associated with stronger monsoon circulation over the Indian subcontinent, a northward shift of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, positive temperature anomalies, increased sunspot numbers and elevated solar activity. Together, these factors appear to have amplified monsoonal rainfall and reinforced humid conditions across the CMZ.

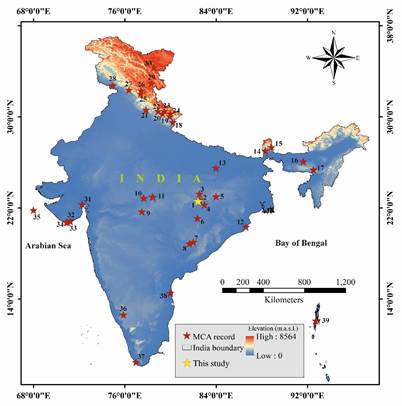

Spatial analysis using Shuttle Radar Topographic Mission Digital Elevation Model data further supported the regional significance of the findings. Correlations between the Raja Rani Lake record and other Medieval Climate Anomaly indicators across the Indian subcontinent indicated that the strong monsoon phase was not a localised phenomenon but part of a broader climatic pattern affecting much of the region.

Scientists involved in the study noted that such high-resolution palaeoclimatic reconstructions of the Indian Summer Monsoon are crucial for improving understanding of present-day monsoon behaviour. By documenting how the monsoon responded to natural climate drivers during the Holocene, the findings offer valuable insights into how current and future monsoon systems may react under ongoing global warming.

The researchers emphasised that the detailed climatic records generated through this study could contribute to the development of more robust palaeoclimatic models. These models, in turn, could help simulate future climatic trends and rainfall patterns with greater accuracy. Beyond scientific modelling, the study also holds societal relevance, as a deeper understanding of long-term monsoon variability can inform evidence-based policy planning related to water resources, agriculture and climate adaptation in a monsoon-dependent country such as India.

– global bihari bureau