WTO Urges Inclusive Policies for AI Trade Boom

Geneva: Artificial intelligence (AI) could catapult global trade in goods and services by nearly 40 per cent by 2040, injecting trillions into the world economy through soaring productivity and plummeting trade costs, but only if policymakers swiftly bridge yawning digital divides and implement inclusive strategies, according to the World Trade Organization’s exhaustive 2025 annual report unveiled today at the Public Forum. Spanning over 200 pages of rigorous analysis, simulations, and fresh survey data, the document casts AI as a general-purpose technology on par with electricity or the internet, propelled by breakthroughs in machine learning and generative models since the early 2000s, yet fraught with risks of exacerbating inequalities unless harnessed through targeted trade, investment, and labour policies.

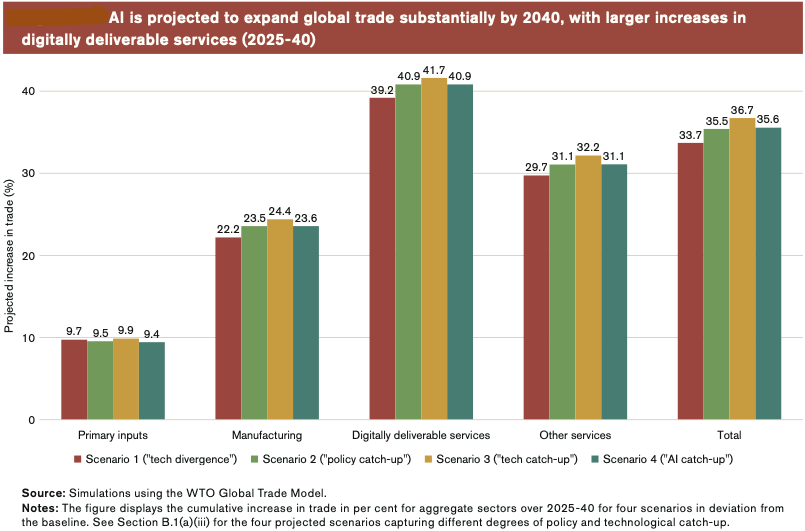

At the heart of the report’s optimism are detailed macroeconomic simulations using the WTO Global Trade Model—a recursive dynamic computable general equilibrium framework calibrated with gravity regressions, task-level occupational data, and productivity estimates ranging from 0.07 to 1.24 per cent annual total factor productivity growth. These projections envision global trade expanding by 34 to 37 per cent and GDP by 12 to 13 per cent by 2040, with digitally deliverable services leading the charge at up to 42 per cent growth. Trade in AI-enabling goods, already totalling $2.3 trillion in 2023, underscores this potential, supplying essential raw materials, semiconductors, and intermediate inputs while providing the diverse datasets AI systems crave for learning and innovation.

The report delineates four nuanced scenarios to illustrate the stakes of policy choices, revealing how inaction could widen global chasms while convergence might democratize gains. In a “technology divergence” baseline, where high-skilled workers reap the most rewards without catch-up efforts, high-income economies could see 13.7 per cent income growth, middle-income 12.4 per cent, and low-income just 7.6 per cent. A “policy catch-up” pathway, closing 50 per cent of digital policy gaps and benefiting medium-skilled labour, narrows this to 11 to 12.4 per cent across groups. The “technology catch-up” scenario, emphasising productivity convergence in AI-automated tasks, delivers the most equitable uplift: 13.7 per cent for high-income, 14.4 per cent for middle-income, and 15.3 per cent for low-income nations. An “AI catch-up” variant, focusing on AI services production, yields similar results to policy catch-up but highlights how trade in AI services can substitute for domestic capacity-building, mitigating the need for every economy to develop full AI infrastructure.

These models incorporate assumptions like fixed savings rates and sequential period-solving, with sensitivity analyses showing that higher AI services growth (up to 38 per cent annually, per UNCTAD estimates) could temper wage gains relative to capital returns by 14 per cent, potentially spurring greater investments in capital stock under intertemporal optimisation. Such granularity exposes AI’s role in reshaping comparative advantages: automation may erode outsourcing incentives in labour-intensive sectors, but global value chains endure, with emerging economies retaining manufacturing edges and advanced ones dominating services—a dynamic warranting ongoing monitoring, as noted in an opinion piece by economist Philippe Aghion.

Trade emerges as AI’s indispensable partner, slashing costs through real-time logistics tracking, predictive maintenance, and automated customs clearance, while dismantling language barriers—as vividly demonstrated by eBay’s machine translation initiative, which amplified U.S. exports to Spanish-speaking Latin America by 17.5 per cent in quantity and 13.1 per cent in revenue. A pioneering WTO-International Chamber of Commerce survey of 158 firms amplifies this, with 89 per cent of AI adopters reporting trade-related perks: 56 per cent in enhanced risk management, over 70 per cent anticipating savings in logistics and communications, and micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) voicing the loudest optimism for cost cuts exceeding 50 per cent.

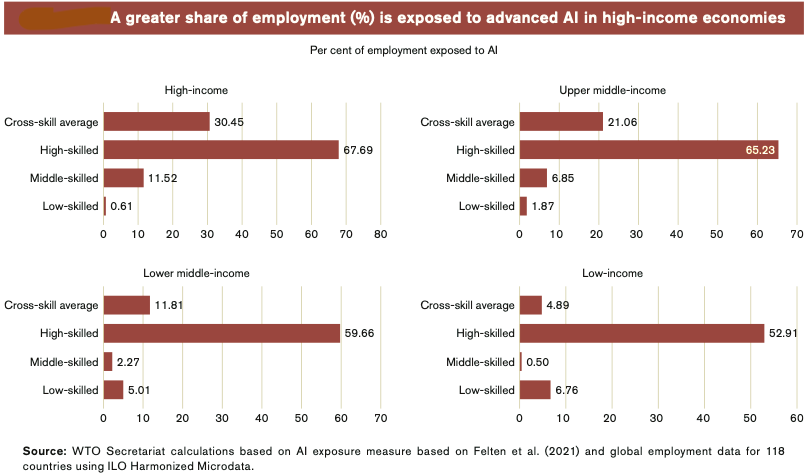

Yet adoption disparities paint a sobering picture, with two-thirds of firms in high-income countries embracing AI compared to less than one-third in low-income ones, and only 41 per cent of small firms versus 60 per cent of large. This mirrors broader digital rifts, where 2.6 billion people—predominantly in developing regions—remain offline, demanding $418 billion in annual infrastructure investments to unlock participation. The report’s new AI Trade Policy Openness Index (AI-TPOI) quantifies regulatory hurdles, tracking a spike in quantitative restrictions on AI-related goods from 130 in 2012 to nearly 500 in 2024, largely imposed by high- and upper-middle-income economies, alongside bound tariffs soaring to 45 per cent in some low-income markets, throttling access to vital inputs.

Sectoral deep dives reveal AI’s tailored promise for developing economies. In agriculture, where 84 per cent of global smallholder farmers reside in low-income nations, tools like PlantVillage’s Nuru app leverage satellite imagery and cloud computing to diagnose crop diseases in real-time, bolstering food security in Kenya and beyond. Education sees AI automating grading to alleviate teacher shortages, finance harnesses it for credit expansion to underserved MSMEs—closing gaps exceeding 30 per cent of GDP in many markets—and healthcare deploys diagnostics to stretch resources in constrained settings, collectively turbocharging inclusive development across high-AI-intensity sectors like IT, finance, and R&D, and medium-intensity ones like chemicals and transport equipment.

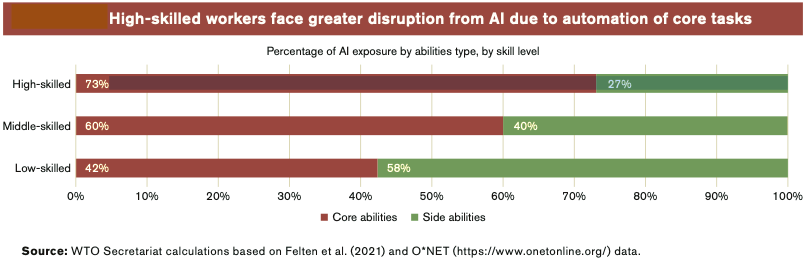

Labour markets, however, brace for turbulence. AI’s productivity jolt—a 15 per cent uplift for customer-support agents, for instance—comes with displacement risks in medium- and high-skilled roles, such as transcription services, projecting a 3 to 4 per cent dip in the skill premium through task substitution. Informal workers, constituting nearly 60 per cent of the global workforce, grapple with regulatory voids on digital platforms, potentially amplifying polarisation akin to U.S. manufacturing’s automation-driven job losses. To navigate this, the report champions inclusive education reforms and labour models like Denmark’s flexicurity, blending generous social supports with aggressive retraining to augment rather than supplant human roles.

Environmental imperatives add another layer, with AI’s voracious energy appetite poised to strain global electricity supplies, though optimised supply chains and resource management could pivot it toward sustainability. Opinion pieces enrich the discourse: Amandeep Singh Gill (United Nations Under-Secretary-General and Special Envoy for Digital and Emerging Technologies) highlights trade’s role in furnishing diverse data for AI evolution, reshaping commerce’s efficiency and scope, while Anu Bradford – a Finnish-American law professor and expert in international trade law, advocate regulatory harmony to avert a “splinternet” of fragmented digital realms.

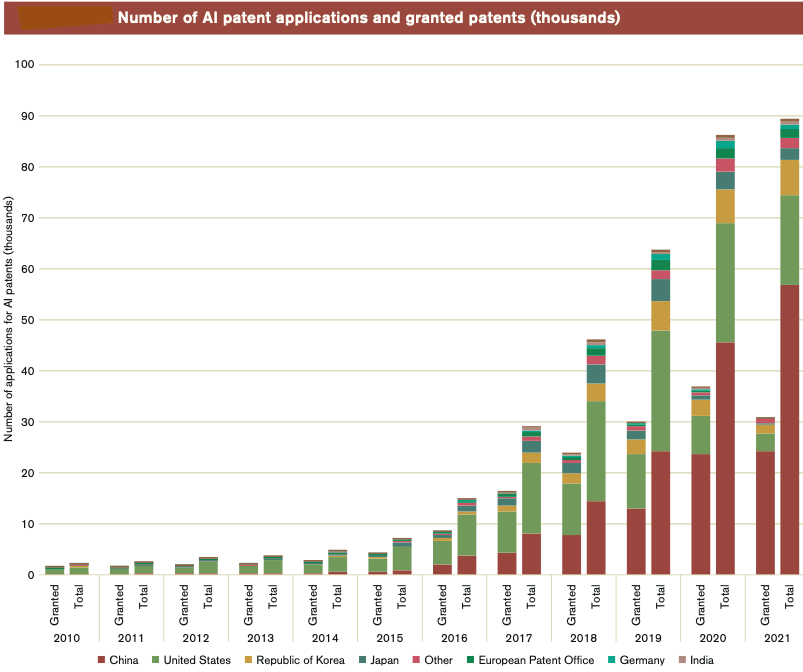

The WTO stands as the linchpin, offering forums for debating 80 AI-specific trade concerns and propelling e-commerce programs. Broader engagement in pacts like the Information Technology Agreement and General Agreement on Trade in Services could slash costs and democratize access, with a 10 per cent uptick in digitally deliverable services trade linked to a 2.6 per cent surge in cross-border AI patent citations, accelerating innovation flows.

WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala captures the urgency in her foreword: “AI has vast potential to lower trade costs and boost productivity. However, access to AI technologies and the capacity to participate in digital trade remain highly uneven. With the right mix of trade, investment and complementary policies, AI can create new growth opportunities in all economies.” She pledges the WTO’s support, echoing calls for investments in critical minerals and energy for resource-rich developing nations to fuel this equitable ascent.

Annexes bolster the report’s rigour, cataloguing AI-enabling products, sectoral classifications, and methodological intricacies, making it an indispensable reference for policymakers and economists alike. The full document is available for download on the WTO website, with printed copies through the online bookshop.

– global bihari bureau