US Trade Preference Lapse Poses Risk to African Industrialisation

Geneva: The expiry of the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) on September 30, 2025, the United States trade preference scheme long credited with opening U.S. markets to sub-Saharan African exports, threatens to undercut the continent’s fragile progress on export diversification and industrialisation, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) warned today.

UNCTAD’s analysis, published alongside its commentary on trade and preferences, emphasises that without prompt renewal, many African exporters of agricultural goods and light manufactures risk losing the preferential margins that have sustained jobs and processing activity for more than two decades.

Also read: Trade Jitters, Tariff Shock Looms for Africa as US Deal Expires

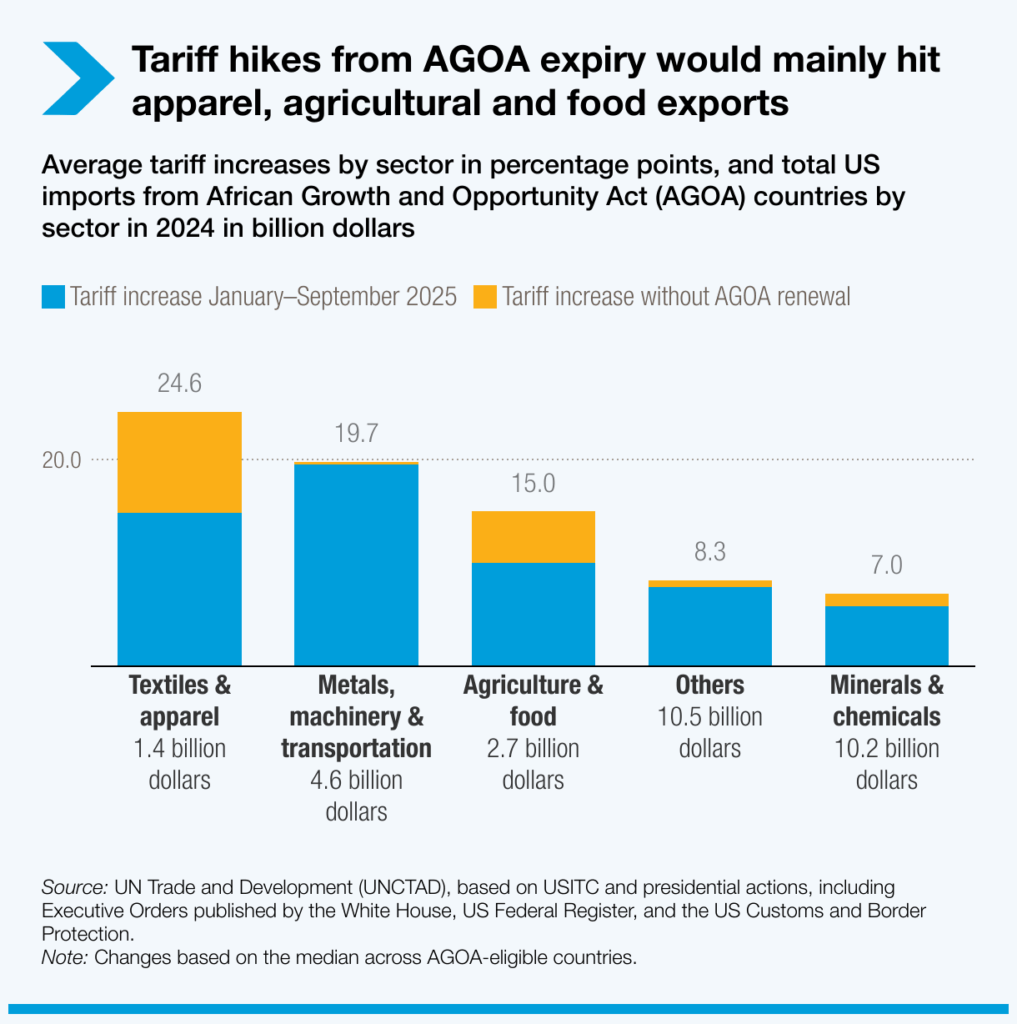

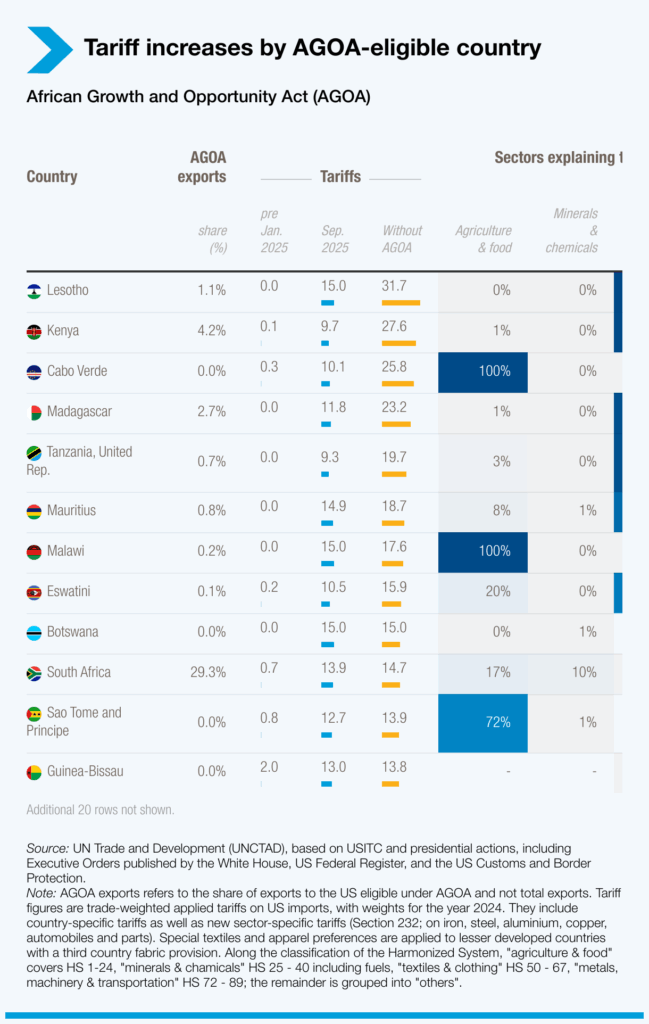

Since its launch in May 2000, AGOA has supported 32 sub-Saharan African countries through preferential access to U.S. markets, particularly in labour-intensive and value-added sectors. The recent expiry of the scheme now jeopardises this support. According to UNCTAD, country- and sector-specific duties the United States introduced since April 2025 have already increased effective tariffs for the “average AGOA country” from under 0.5 per cent to roughly 10 per cent. For key sectors such as apparel, processed fish, dried fruits, other agro-food products, metals, machinery, and transportation, these tariff hikes have triggered double-digit increases, creating an immediate shock to exporters who previously relied on duty-free access.

The practical impact is highly uneven. Light-manufacturing and agro-food exports, including textiles and apparel, processed fish, dried fruits, and packaged foods, bear the brunt of the shock. Lesotho is illustrative: roughly one-third of its U.S. exports were tied to AGOA preferences, primarily in apparel factories employing an estimated 30,000–40,000 workers, mostly women.

The sudden loss of preferential access threatens both livelihoods and local processing activity. African exporters already face increased trade barriers, and the lapse of AGOA could lead to a “second wave” of tariff increases, as country-specific and sectoral levies would be applied atop most-favoured-nation rates instead of current preferential treatment. For many agricultural and manufactured products, these tariffs would be two to three times higher than those applied to fuels and minerals.

By contrast, exports of fuels, metals, and many mined commodities are comparatively insulated. Countries whose export baskets are commodity-heavy — including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, and Angola — face minimal tariff increases because their primary exports already benefit from low MFN rates or exemptions from additional duties. More diversified economies, such as South Africa, have experienced significant tariff increases due to country-specific and sectoral levies earlier in 2025, but remain somewhat less exposed to AGOA’s expiry.

UNCTAD warns that the lapse could further hinder Africa’s industrialisation and export diversification. Since most U.S. imports from AGOA-eligible countries already consist of fuels, metals, and agricultural raw materials, the end of the trade pact could exacerbate commodity dependence. Labour-intensive sectors like apparel and agriculture are particularly at risk, with negative consequences not only for export diversification but also for poverty reduction and women’s employment. The experience of Madagascar, whose AGOA eligibility was suspended between 2009 and 2015 following a coup, illustrates the dangers of sudden market exclusion and the potential for delayed recovery.

Small exporters specialising in apparel and agricultural processed goods — Lesotho, Kenya, Cabo Verde, Madagascar, and the United Republic of Tanzania — could see average trade-weighted U.S. tariffs double or more, in some cases exceeding 20 per cent, if AGOA is not renewed. Such increases could render African products costlier in U.S. markets than similar goods from developed countries, undermining efforts to move up the value chain and reduce reliance on raw commodity exports. UNCTAD highlights that expiry would disproportionately raise protection on activities African governments have sought to nurture — small-scale processing, export-oriented agribusiness, and labour-intensive textiles — while leaving commodity exports comparatively unaffected, risking a reversal of two decades of diversification efforts.

Governments in the region have reacted with concern. South Africa’s Trade Minister Parks Tau, speaking on 30 September 2025, said he remained “optimistic” that AGOA would be renewed, pointing to continuing bipartisan support in the U.S. Congress, while noting Pretoria’s engagement over tariffs introduced earlier this year. Lesotho’s Trade Minister Mokhethi Shelile told reporters on 24 September 2025 that a delegation to Washington had received informal assurances from some U.S. lawmakers about a one-year extension, but stressed that formal action in Washington remained uncertain. Analysts note that such short-term measures could blunt the immediate shock but do not substitute for durable, rules-based market access that encourages investment and supply-chain planning.

UNCTAD stresses that predictable, long-term preferences — or negotiated reciprocal arrangements locking in market access — are far more conducive to industrial upgrading than ad hoc renewals. Firms considering investments in factory lines, cold chains, or other value-adding capacity require multi-year certainty; the threat of punitive tariffs at short notice discourages capital commitments and can redirect investment back toward commodity extraction. The lapse of AGOA could reduce female participation in export manufacturing, weakening poverty-reduction pathways dependent on stable employment. The case of Madagascar remains a cautionary example of the long-term damage sudden exclusion can inflict on export performance.

UNCTAD’s call is pointed: policymakers in the United States should weigh the broader development costs of abrupt preference removal and consider mechanisms that preserve market access while encouraging regional integration and upgrading, including through the African Continental Free Trade Area. Without renewal, the agency concludes, many African exporters face more than a temporary tariff shock — they risk a structural setback to diversification and industrialisation, with immediate socio-economic repercussions for jobs, investment, and inclusive growth.

– global bihari bureau