DR Congo Ends 16th Ebola Outbreak After 42-Day Lull

Ebola Stopped in Bulape—Surveillance Starts Again

Kinshasa/Geneva: The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) today declared an end to what officials count as its sixteenth Ebola virus disease outbreak since the pathogen was first identified in the country in 1976. The announcement, delivered by Minister of Public Health, Hygiene and Social Welfare Dr Samuel Roger Kamba, came after 42 days—two full incubation cycles—without the detection of a new case. The last patient had been discharged from a treatment centre on October 19, and the government now claims the transmission chain has been broken.

Authorities and international partners are visibly eager to portray the operation as a success of modern outbreak control. The Ministry of Health, backed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and a familiar list of global response partners, repeatedly cited speed and coordination as reasons the virus failed to spread beyond the initial rural cluster.

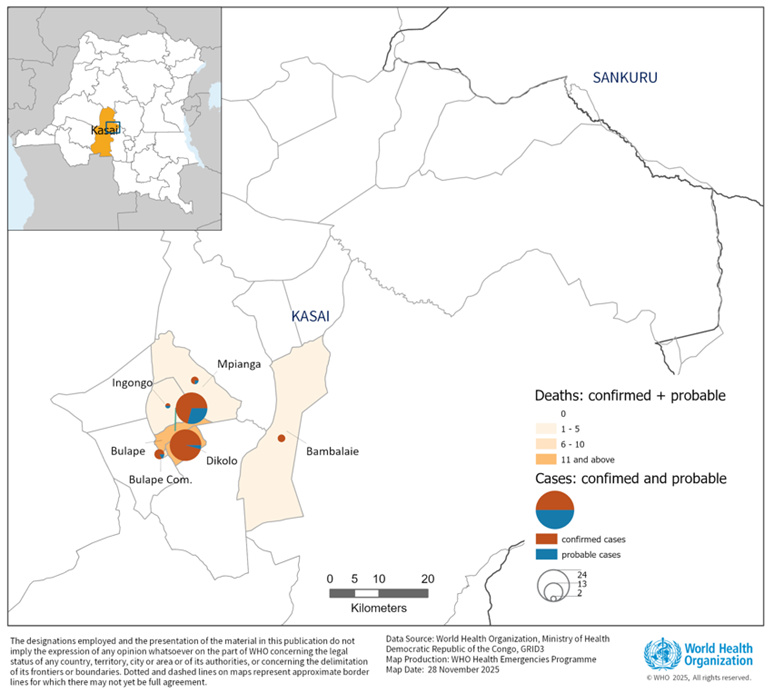

Bulape Health Zone, the outbreak’s epicentre, is known in medical logistics circles not for its easy access but for its dirt roads, unreliable telecommunications, and a chronic scarcity of clinical equipment. That 64 cases—53 confirmed and 11 listed as probable—were confined to six health areas is being framed as proof that rapid containment is possible when money, expertise and infrastructure arrive early enough.

The numbers, however, relay a familiar brutality. Forty-five people died, a case fatality rate higher than 70 per cent. Three of the five infected frontline health workers did not survive. The worst-hit localities, Dikolo and Bulape, accounted for more than three-quarters of the caseload and more than 80 per cent of the deaths. The outbreak spread through hospitals and funerals before authorities reached a level of control sufficient to interrupt transmission. While the official language focuses on epidemiological success and resilience, the human cost—especially among children in the early cluster—will never be documented with the same level of confidence as the tally sheets.

Still, the government and WHO insist that the response infrastructure built during the crisis marks a turning point. More than 112 WHO experts were dispatched, over 150 tonnes of supplies were flown or driven in through a temporary airbridge, and the new modular Infectious Disease Treatment Module—designed to provide safer conditions for staff and more dignified care for patients—was commissioned for the first time in an active Ebola zone. There is no public accounting yet of the total operational bill, nor clarity on how much of the new infrastructure will remain usable once emergency budgets wind down.

Vaccination, now central to Ebola strategy, was rolled out aggressively. More than 47,500 people received the rVSVΔG-ZEBOV-GP (Ervebo) vaccine through a ring vaccination model that was later expanded to broader geographic coverage around hotspots. The doses came from the global stockpile funded by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, which did not miss the opportunity to highlight that prompt access to vaccines, cold-chain logistics, and delivery funding were decisive. The assertion that Ebola can now be “rapidly brought under control” will likely be read differently in communities that continue to live with the burden of disrupted livelihoods, vacant hospital beds, and the stigma attached to survivors.

Rehabilitation is now the language of the day. A piped water system recently installed to shore up the Bulape hospital’s clinical needs is also being presented as a long-term asset for residents. Reconstruction work on hospitals and outlying facilities continues with the explicit aim of strengthening the health system rather than merely patching it until the next emergency. A survivor care programme—largely invisible to the cameras—is meant to address lingering medical complications and social fallout. Whether these promises translate into resources six months down the line will depend on political mood, donor patience, and whether other crises overshadow Congo’s routine battles with preventable disease.

In Geneva, World Health Organization Director-General Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus congratulated Congolese authorities and communities, while reminding reporters of the broader context. “When Ebola devastated West Africa a decade ago, there were no approved vaccines or therapeutics. Now we have both,” he said, adding that an outbreak of Marburg virus disease in Ethiopia has already claimed eight lives and is now the organisation’s immediate concern. For WHO officials, victory statements are always followed by caveats.

Congo has learned the hard way that the end of an outbreak is rarely the end of risk. The Ebola virus can persist in survivors for months in immune-privileged parts of the body, and spillover from wildlife remains a constant threat in forest regions. The Ministry of Health has launched a 90-day phase of heightened surveillance across Kasai and neighbouring provinces. Border checkpoints—including those within 100 to 200 kilometres of Angola—have been instructed to continue screening travellers. Risk communication teams will continue to track rumours, reinforce scientific messaging, and try to keep survivor stigma from mutating into a public health barrier.

Internationally, no travel or trade restrictions have been recommended. But internally, Congolese health authorities know they remain underpowered. The country is simultaneously managing outbreaks of mpox, cholera and measles, and is navigating a prolonged economic and political crisis that weakens administrative capacity and donor leverage. For all the optimism that follows today’s declaration, even WHO’s official risk assessment concedes that a future outbreak is not just likely but expected.

For the moment, Kinshasa is celebrating a line crossed on a calendar: 42 days without Ebola. For a country that has counted sixteen such outbreaks in less than half a century, optimism will remain cautious. In the congested offices of public health managers and the wards that have seen too many body bags, there is no illusion that the virus has disappeared. Only that it has been forced—for now—to retreat.

– global bihari bureau