Shahid Udham Singh

[the_ad_placement id=”adsense-in-feed”]

Exclusive on Udham Singh’s Death Anniversary

By Shivnath Jha*

By Shivnath Jha*

Udham Singh (26 December 1899 – 31 July 1940) was a revolutionary of the Ghadar Party. The great martyr had shot and killed Michael O”Dwyer, who as Lieutenant Governor of Punjab endorsed the massacre on Baisakhi day in 1919.

[the_ad_placement id=”content-placement-after-3rd-paragraph”]

Singh had assassinated O’Dwyer in London on 13 March 1940. He was subsequently tried and convicted of murder and hanged on July 31, 1940.

We remember his ultimate sacrifice today. But at the same time I feel it prudent to see what we have done for the descendants of such selfless freedom fighters to whom we owe our Independence.

Udham Singh might have borne the burden of avenging one of the most gruesome colonial acts in Indian history–the infamous Jalianwala Bagh massacre–but his descendants were condemned to carry the burden of penury.

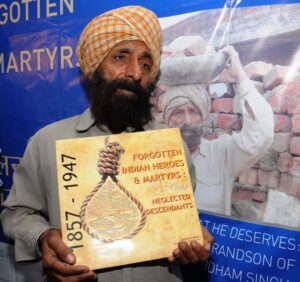

Jeet Singh was no ordinary Indian but grand-nephew of Udham Singh. When I located him in 2012, he was working as a labourer at a construction site in Punjab.

The then 55-year-old Jeet lived in Sangrur village of Punjab with his two sons, all of whom lived a miserable life despite promises of succour by government functionaries, including late President Giani Zail Singh.

Giani Zail Singh, then chief minister of Punjab (and later President of India), got Udham Singh’s ashes from England in 1974 and handed them over to his sister. A memorial was built where his ashes were buried; the doors of this neglected memorial are opened just four times a year to pay tributes to the martyr.

When I traced Jeet Singh, he was working as a labourer at a construction site for Rs.120 a day. Given the family’s circumstances, his son Jagga Singh managed to study only till Std. X.

I had felt ashamed of myself. I desperately wanted to do something for the descendants of one of the pillars of our freedom movement. But was that easy?

Exploring possibilities of some government job for Jagga, I approached the Commissioner’s office at Sangrur. It was in Sangrur district of Punjab where the martyr was born.

“Of course we acknowledge Udham Singh’s sacrifice,” Kumar Rahul, the then Deputy Commissioner of Sangrur district, told me. “We’ve re-named his hometown Sunam after him; we are spending crores to build a museum for him,” he informed. But giving his sister’s great-grandson a job? That was out of question, though the young man had a letter of recommendation from former Chief Minister Amarinder Singh himself. “A job is a recurring expenditure; besides, rules don’t permit us to give jobs to anyone but the direct descendants of freedom fighters,” the Deputy Commissioner told us point blank. He went on: “Once we bend the rules, who knows how many sisters of Udham Singh will come crawling out? He can’t claim a job as a right; out of courtesy, we have helped him. We’ve given him a bus pass.”

I could see the anger in Jagga Singh’s eyes: “I am not asking for crores; I want a job. I will work, I don’t want charity.”

“But there should be an opening,” Rahul consented. The DC helplessly pointed out that how for years, there had been a freeze on government jobs by the Punjab government. “We are a poor government,” he confessed.

Because of our concerted efforts to rehabilitate the great martyr’s descendants through a pictorial coffee-table book Forgotten Indian Heroes and Martyrs: Their Neglected Descendants-1857-1947, chronicling the lives of more than 22 such families of descendants of the martyrs of India”s freedom struggle, Rajya Sabha MP and founder of the Lokmat media group Vijay Darda had honoured the memory of Udham Singh on the occasion of Baisakhi in 2014.

Because of our concerted efforts to rehabilitate the great martyr’s descendants through a pictorial coffee-table book Forgotten Indian Heroes and Martyrs: Their Neglected Descendants-1857-1947, chronicling the lives of more than 22 such families of descendants of the martyrs of India”s freedom struggle, Rajya Sabha MP and founder of the Lokmat media group Vijay Darda had honoured the memory of Udham Singh on the occasion of Baisakhi in 2014.

He had then handed over a cheque of Rs 11 lakh to Jeet Singh. The amount was collected through contributions by his media group and from some individual philanthropists, in 2014.

Jeet Singh was moved to tears at the felicitation and he mumbled “it feels good to be respected and loved by the people of the country”.

There was nothing about Udham Singh in our book that people did not know already. I have but changed the perspective of the story by encapsulating the present lives of his descendants. The neglect of Jeet Singh was an example of a black page in our system–one of which we ought to be ashamed of.

Here I endorse the view of Darda that if the government can take care of its Parliamentarians for life, don’t the families of our national heroes need some attention. I hope various state governments will wake up to the cause of such families.

*The writer is a senior journalist and co-author of Forgotten Indian Heroes and Martyrs: Their Neglected Descendants-1857-1947.

[the_ad_placement id=”sidebar-feed”]

Like!! Great article post.Really thank you! Really Cool.

Truly thought provoking article.

I wish that was a way to form a TRUST to assist them.

Shiva