Prime Minister Narendra Modi along with world leaders at the AI Impact Summit dinner and cultural programme at Bharat Mandapam, in New Delhi on February 18, 2026.

By Deepak Parvatiyar*

By Deepak Parvatiyar*

Who Will Shape AI’s Future: Markets or Nations?

Rare Earths, Ethics and India’s AI Moment

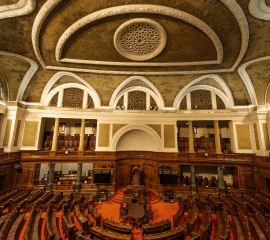

New Delhi: When more than twenty heads of state and government converged in New Delhi for the India AI Impact Summit 2026, the spectacle went far beyond conference halls and technical panels. A Guinness World Record for over 250,000 AI responsibility pledges collected in twenty-four hours unfolded alongside a dense calendar of bilateral meetings, institutional launches and joint declarations. Together, they created a carefully choreographed narrative: artificial intelligence is no longer only a domain of engineers and corporations but a field of public legitimacy, diplomatic alignment and strategic positioning. The signal lay not just in numbers or ceremonies, but in what India chose to communicate—about who should shape AI’s future, on what terms, and for whose benefit.

Also read: India AI Summit Turns Infrastructure Into Statecraft

This choreography reached its political high point as Prime Minister Narendra Modi prepared to address the Leaders’ Plenary, following his earlier inauguration of the AI Expo on February 16, where he walked through pavilions and framed artificial intelligence through ancient Indian reflections on intellect and responsibility. The February 19 programme itself carries a layered message: a restricted-access plenary in the morning where heads of government would commit to principles of AI governance; a Chief Executive Officers’ roundtable with figures such as Sam Altman, Sundar Pichai and Jensen Huang; and side events on artificial intelligence for the Sustainable Development Goals. Even the city bore the imprint of the gathering, with traffic diversions around Pragati Maidan and invite-only access until midday, underlining that this was diplomacy unfolding in real time, not a distant policy seminar.

The presence of leaders such as French President Emmanuel Macron, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić and Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres placed the summit firmly in the lineage of earlier global AI gatherings in the United Kingdom and France, but with a decisive geographical and political shift. This was the first major artificial intelligence summit hosted in the Global South, and India did not attempt to conceal its ambition to recast itself as a bridge between industrial powers and developing nations, between technology giants and public institutions, between innovation and governance. Alar Karis, President of the Republic of Estonia, praised India’s leadership in digital public infrastructure, stating it’s shaping the global conversation on technology, governance, and inclusion.

Symbols were matched by infrastructure. Union Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw announced the expansion of India’s national AI compute pool with the addition of 20,000 high-end graphics processing units, building on the existing IndiaAI Mission. Access to this public compute capacity at subsidised rates for startups, researchers and students was presented as a counter-model to the concentration of AI power within a few global corporations. At the same time, corporate commitments underscored how quickly diplomacy was translating into capital: Google announced over fifteen billion dollars in artificial intelligence infrastructure investments, Microsoft unveiled new talent-upskilling partnerships, and NVIDIA confirmed the expansion of its “Shakti Cloud” initiative with tens of thousands of advanced processors hosted on Indian soil.

These announcements revealed the summit’s deeper logic. Artificial intelligence is being positioned as strategic infrastructure, comparable to railways or ports in earlier eras. Whoever builds and governs it will shape economic flows, labour markets and political influence. India’s pitch is that this infrastructure must be accessible, interoperable and publicly accountable. Its language of “Digital Public Infrastructure” and “AI for All” stands in contrast to the corporate-led model dominant in the United States and the state-centralised model pursued in China. The summit thus became a stage for an emerging geopolitical philosophy: digital sovereignty without digital isolation, and innovation without monopolisation.

Yet beneath this vision of inclusion lay a more complex material story. Artificial intelligence depends on rare earth minerals, lithium, copper and vast energy inputs. India’s latest national budget places strong emphasis on the exploration and processing of critical minerals, linking technological autonomy to extractive capacity. That connection has provoked anxiety among environmental groups, particularly regarding mining prospects in ecologically fragile regions such as the Aravalli range and the Western Ghats. These landscapes are biodiversity hotspots and water catchments; their transformation into mineral corridors for data centres and battery supply chains exposes a fundamental contradiction between “humane AI” and the physical costs of building it.

Summit sessions on sustainability acknowledged this tension. Commitments were made to reduce the energy and water footprint of data centres by up to thirty-five per cent through cleaner power, efficient cooling systems and advanced hardware. Partnerships with global technology firms focused on green computing and circular supply chains. Yet the question lingered unresolved: can an ethics of inclusion coexist with extraction from vulnerable ecologies? This dilemma is not uniquely Indian. It echoes debates in Australia over lithium mining, in Latin America over copper, and in Africa over cobalt. What distinguishes the New Delhi summit is that it placed this contradiction within a framework of public accountability rather than corporate inevitability.

Another axis of concern ran through discussions on misinformation, deepfakes and child protection. Under the summit’s “Planet” pillar, sessions focused on artificial intelligence safety, job displacement and the destabilising effects of automated propaganda. These were not abstract fears but immediate political risks, especially in democracies where trust in institutions is fragile. By foregrounding these themes alongside innovation showcases, India sought to position itself as a convenor not only of optimism but of restraint, a country willing to host uncomfortable conversations about technology’s harms as well as its promises.

The civic dimension of this effort was visible in the Guinness World Record itself. More than 250,000 students and young citizens pledged to use artificial intelligence responsibly, transforming ethics into a mass ritual rather than an elite declaration. Youth-focused initiatives such as the YUVAi Global Challenge and gender-equity programmes like “AI by HER” reinforced this attempt to democratise technological discourse. In parallel, six AI Impact Casebooks displayed over 170 innovations in health, agriculture, education and disability access, presenting artificial intelligence as a tool of everyday governance rather than speculative futurism.

Diplomacy unfolded in quieter corridors as well. India signed a Joint Declaration of Intent with Germany on telecommunications, quantum communication and digital governance, and deepened its strategic technology dialogue with Sweden around fifth- and sixth-generation mobile networks, Open Radio Access Networks and cybersecurity. Both engagements were explicitly linked to cooperation within the International Telecommunication Union, where India has sought support for leadership positions and for hosting the Plenipotentiary Conference in 2030. In this sense, the summit functioned not only as a marketplace of ideas but as a rehearsal for multilateral rule-making.

India also advanced its technology diplomacy with Spain. During bilateral meetings on the margins of the summit, India and Spain agreed to deepen cooperation in artificial intelligence, digital public infrastructure and semiconductor-related research, with a focus on responsible AI governance and skills development. Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez underlined the need for democratic countries to align standards on data protection and algorithmic accountability, while Indian officials highlighted opportunities for joint projects linking Europe’s regulatory experience with India’s large-scale digital platforms. The engagement signalled New Delhi’s intent to broaden its AI partnerships beyond traditional technology powers and anchor them within the European Union’s evolving regulatory framework.

The scale of the gathering soon exceeded expectations. The AI Expo was extended to February 21, 2026, due to daily footfall crossing ten thousand visitors, with more than three hundred exhibitors and over thirty national pavilions. The contrast between the controlled space of leaders’ meetings and the open arena of public exhibitions reflected the summit’s dual identity: part high diplomacy, part civic spectacle.

What ultimately distinguished the India AI Impact Summit was its insistence that artificial intelligence is now inseparable from foreign policy. Technology has become a language of alignment and a measure of trust. By hosting presidents, prime ministers, corporate chiefs and students under one roof, India attempted to show that the governance of algorithms cannot be left to markets alone or to security blocs alone. It must be negotiated across cultures, economies and ecosystems.

Yet the summit also exposed unresolved questions. Can India maintain an open, subsidised compute model while attracting billions in corporate investment? Can it reconcile rare earth extraction with ecological stewardship? Can youth pledges mature into enforceable policy? And can a middle-power democracy truly mediate between rival technological empires without becoming dependent on either?

The answers will not emerge from declarations alone. They will be tested in how infrastructure is built, where minerals are mined, how standards are written, and who gains access to computing power. For now, the New Delhi gathering has done something rare in global technology politics: it has made artificial intelligence visible not merely as code and capital, but as culture and conscience. In doing so, India has placed itself at the centre of a debate that will define the next decade of geopolitics—whether the future of intelligence will belong to a few, or to many.

*Senior journalist