From Tap to ICU: Tracing Indore’s Waterborne Outbreak

A City’s Clean Image, Undone by Its Drinking Water

As a medical professional observing this unfolding public health emergency, the water contamination crisis in Indore’s Bhagirathpura locality represents a classic—and entirely preventable—explosive outbreak of acute gastroenteritis, driven by faecal–oral transmission through contaminated municipal drinking water. This is not a minor episode of “loose motions”, but a severe systemic illness marked by profuse vomiting and diarrhoea, rapidly progressing to dehydration, electrolyte imbalance, acute kidney injury (AKI), and, in fatal cases, cardiac arrest. The clinical pattern—sudden onset across households, affecting infants, adults and the elderly alike—is characteristic of heavy pathogen exposure through a shared water source.

The crisis began around December 24–25, 2025, when residents of the densely populated Bhagirathpura area reported foul-smelling and bad-tasting tap water supplied through municipal pipelines carrying water from the Narmada River. Within days, large numbers of residents developed gastrointestinal illness after consuming this water. The speed and simultaneity of cases across the locality immediately pointed to community-wide exposure, the epidemiological hallmark of a contaminated drinking-water supply rather than sporadic illness or foodborne infection.

Also read: NHRC Probes Bhagirathpura Water Deaths in Indore

From a medical standpoint, the disease course observed was severe and unforgiving. Intractable vomiting and diarrhoea led to rapid fluid loss and dehydration. In vulnerable individuals—particularly infants, elderly residents, and those with limited physiological reserve—this dehydration progressed to electrolyte imbalance and acute kidney injury. Where deaths occurred, the pathway was medically consistent and well recognised: severe dehydration leading to electrolyte derangement, precipitating AKI, followed by cardiovascular collapse and cardiac arrest. This sequence is a documented outcome of severe diarrhoeal disease when rehydration is delayed or inadequate. Some severe cases were also reported to have associated jaundice or systemic complications, reflecting critical illness rather than isolated gastrointestinal upset.

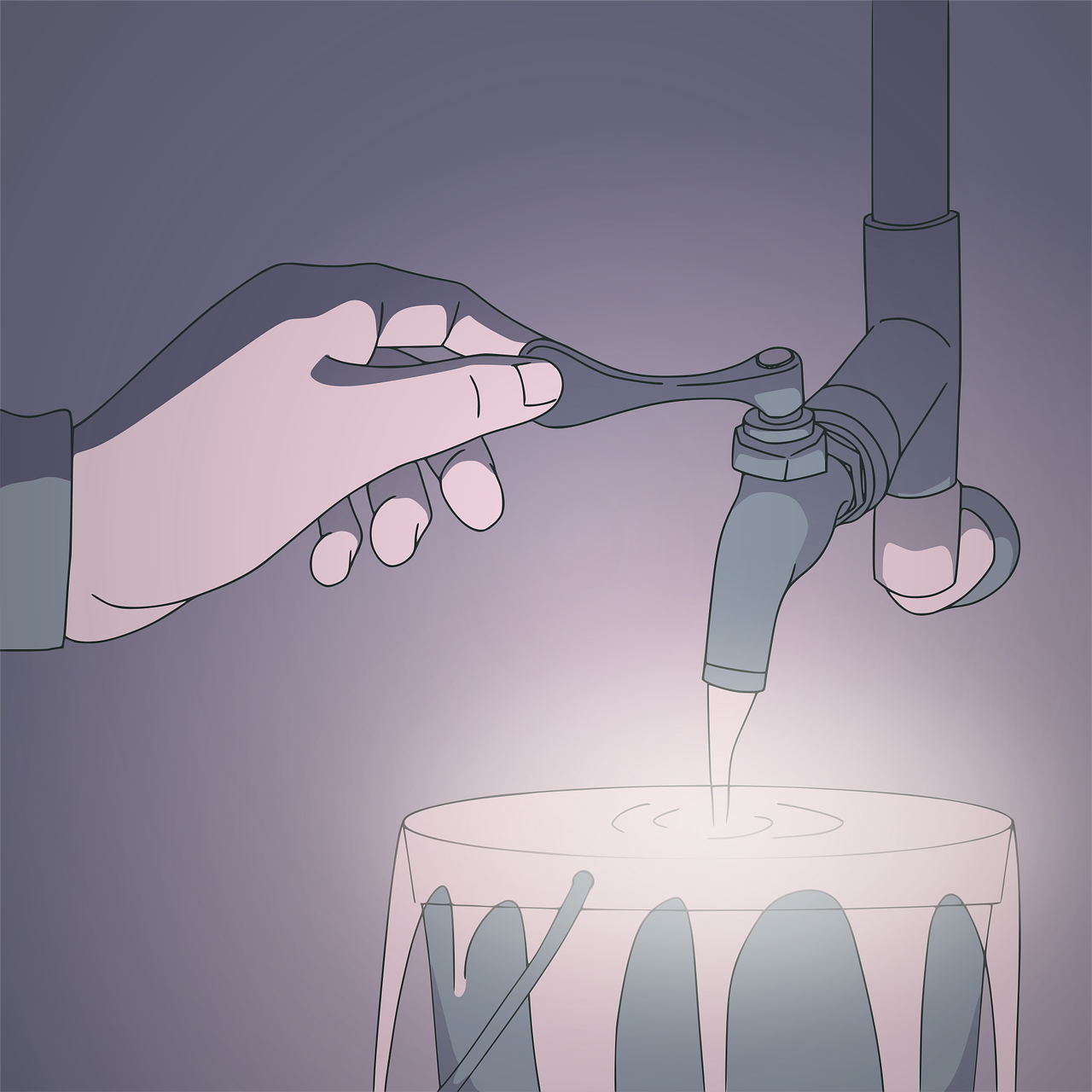

There has been no evidence of chemical poisoning. The outbreak was caused by faecal contamination of the municipal drinking-water supply. A leakage in the main water pipeline allowed sewage and drainage water to mix with potable water. A key contributory factor was the construction of a toilet at the Bhagirathpura police check-post, with waste channelled into a pit located directly above the pipeline. Seepage through a loose joint allowed sewage to enter the drinking-water line—a structural failure with fatal consequences.

At the time of initial reporting, laboratory confirmation was pending. Water and stool samples had been collected, with PCR and culture reports awaited. Nevertheless, the clinical and environmental pattern strongly suggested faecal–oral transmission by common waterborne pathogens typically implicated in such outbreaks. These include enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC), frequently responsible for explosive waterborne diarrhoeal outbreaks; Shigella species, associated with severe diarrhoea and systemic toxicity; Salmonella and other enteric organisms; and, less likely but still possible, Vibrio cholerae, though its characteristic epidemic profile was not clearly evident. Subsequent government testing later confirmed bacteriological contamination of water samples, ruling out chemical toxins, while organism-specific PCR and culture identification remained pending at the time of confirmation.

In the absence of confirmed isolates, management appropriately prioritised supportive care. Rehydration—oral or intravenous—formed the cornerstone of treatment, aimed at correcting fluid loss and restoring electrolyte balance. Antibiotics were used judiciously and primarily in severe or strongly suspected bacterial cases, with agents such as ciprofloxacin or azithromycin considered for suspected Shigella or Campylobacter, and ceftriaxone reserved for critically ill patients. Many cases were managed without antibiotics, recognising that unnecessary antimicrobial use offers no benefit in viral or self-limiting illness and carries the risk of resistance.

The scale of the outbreak is best understood through its epidemiological ratios. Health surveys covering a population of 39,854 identified over 2,456 affected residents, yielding an attack rate of approximately 6.1 per cent. In practical terms, this translates to roughly one illness per three households, or every 16th person in the locality falling sick—clear evidence of an urban explosive outbreak with heavy contamination.

Hospitalisation data further underscored the severity. Two hundred and twelve patients required admission, with approximately 50 discharged and 162 still hospitalised across government and private facilities, including MY Hospital and Shalby Hospital. Twenty-six patients required intensive care. These figures indicate that 8.6 per cent of those affected were sick enough to require hospitalisation, nearly one in eleven, and that 12.3 per cent of admitted patients deteriorated to ICU-level illness. Put differently, approximately one in every 94 affected individuals became critically ill. For diarrhoeal disease, this represents a high-severity signal, far beyond routine gastroenteritis.

Fatality figures remain contested due to ongoing verification. Senior district sources and multiple media reports have cited more than ten deaths, while the Mayor has acknowledged seven. Initial official figures from the Chief Minister’s office ranged between four and seven confirmed contamination-linked deaths, while residents have claimed numbers as high as thirteen. As of December 31, 2025, the government was still differentiating contamination-related deaths from natural causes, and no final official toll had been released. Based on available data, the approximate death rate stands at 0.8 per cent. Those reported deceased, compiled from multiple credible sources, include a five- to six-month-old infant, several women in their working and middle years, and elderly residents—illustrating the indiscriminate reach of the outbreak.

From an epidemiological perspective, waterborne outbreaks of this nature typically peak 10 to 14 days after initial exposure. At the time of assessment, Bhagirathpura appeared to be at day six or seven, only halfway to the expected peak. Using conservative modelling, the outbreak could stabilise at an attack rate of 8 to 15 per cent, translating to approximately 4,000 total cases, around 340 hospitalisations, 30 to 40 ICU admissions, and more than 30 deaths, assuming a conservative case-fatality rate of 0.8 per cent. In practical terms, if intervention remains committee-level rather than pipeline-level, Indore risks drifting toward this trajectory. This is why public health professionals tend to raise alarms early: pathogens follow epidemiological curves, not political timelines.

The outbreak remains controllable, but the window is narrowing. Immediate measures with proven impact include emergency chlorination of the water supply, door-to-door distribution of oral rehydration solution and zinc, fast-track admission protocols for elderly patients to reduce ICU burden, and GIS-based mapping of pipelines to prevent a second wave.

The incident has punctured Indore’s long-cultivated image as India’s cleanest city and triggered sharp political controversy. Administrative action has included the dismissal of in-charge sub-engineer Shubham Shrivastava, the suspension of Shaligram Sitole and Yogesh Joshi, and the formation of a three-member probe panel headed by IAS officer Navjeevan Panwar. Emergency public-health measures have been implemented, including medical camps, water tankers, free treatment orders, and ex-gratia compensation of ₹2 lakh for families of the deceased. The Madhya Pradesh High Court has sought a status report and directed that treatment be provided free of cost.

Indore’s tragedy illustrates a fundamental public-health truth: collapse often begins invisibly, underground, long before it becomes visible above ground. A city celebrated for cleanliness awards allowed a drinking-water pipeline to pass beneath a sewage pit. Microbes were indifferent to trophies, titles or civic rankings. They exploited a loose joint and followed biology’s rules. Infrastructure integrity, not accolades, is what ultimately protects lives.