By Nava Thakuria*

By Nava Thakuria*

PLF 2025: Roots Found, Tears Shed, Hope Renewed From Tiwa Villages to Jnanpith Dreams

Assam’s Litfest Season Peaks as PLF Bids Emotional Goodbye

Guwahati: The third Pragjyotishpur Literature Festival (PLF) 2025 wrapped up at Srimanta Sankaradeva Kalakshetra in Guwahati yesterday evening, leaving behind the kind of lingering conversations that define a proper literary adda—those unhurried exchanges over black tea where stories from the past spill into plans for tomorrow, much like the endless flow of the Brahmaputra itself.

Organised by the Sankardev Education and Research Foundation under the theme “In Search of Roots,” this three-day gathering had drawn authors, critics, journalists, and readers from across Assam and beyond, all united in a quiet mission to reclaim the threads of cultural heritage that often get lost in the rush of modern life. The valedictory ceremony, held in the gracious presence of PLF president Phanindra Kumar Dev Choudhury and chief guest Sahitya Akademi awardee Dr Apurba Kumar Saikia, felt like a family farewell: proud, a little teary, and full of unspoken promises.

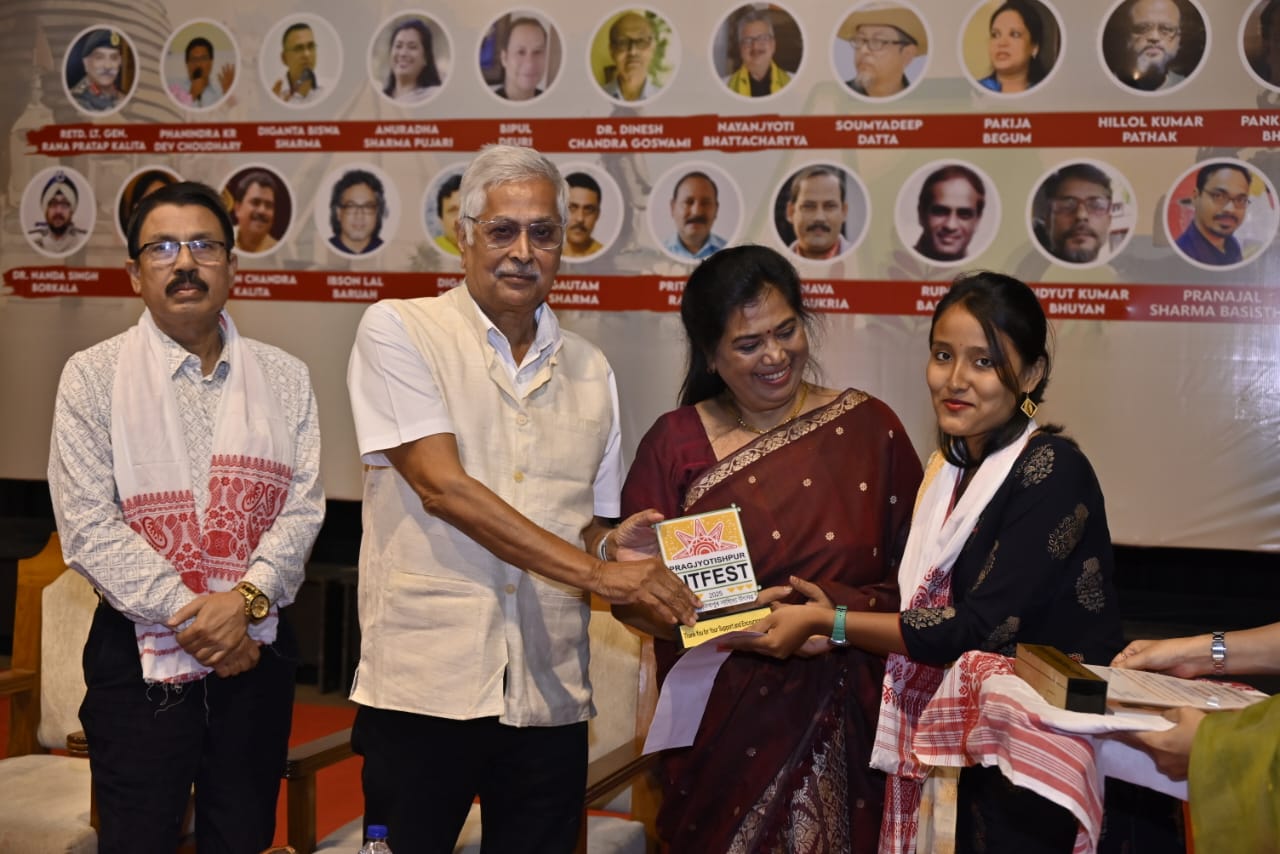

At the heart of it all were the PLF Awards 2025, presented to two writers whose paths embodied the festival’s spirit—one a veteran digging deep into forgotten histories, the other a young voice just starting to find her footing. Eminent Tiwa scholar and essayist Moneswar Deori, a tireless researcher on society, literature, culture, and history, received the main PLF Award. Having authored over 20 books after resigning from a senior government job to commit to literature and journalism fully, Deori has long focused on the Tiwa community’s identity, often trekking through western Assam’s villages to record events and oral traditions overlooked by mainstream narratives. Accepting the honour—a citation, traditional cheleng chador, and cash prize—he expressed deep emotion, noting how his works on districts like Morigaon, Nagaon, and Karbi Anglong could one day aid scholars and historians in crafting a more complete story of Assam. It was the kind of moment that hit home for anyone who’s ever chased a fading folktale, only to wonder if it mattered.

Sharing the stage was Srotashwini Tamuli, the emerging short-story writer and research scholar at Birangana Sati Sadhani State University in Golaghat, who took home the PLF Youth Award for her collection Jalkhar. At an early point in her career, she spoke plainly about the weight of the recognition: it sharpened her sense of duty in creative writing, turning every unwritten line into something more urgent. For the packed hall—filled with college students scribbling notes and retirees nodding along—it was a reminder of how festivals like this hand the baton to the next generation, one award at a time.

Dr Apurba Kumar Saikia’s closing address perfectly captured the room’s mood. He lauded the festival’s three days of exploration, from keynote reflections to heated panels, and voiced hope that PLF would soon rank among India’s top litfests. More than that, he saw it sparking real fire in budding writers, translators, journalists, theatre and film workers, and everyday readers who might otherwise let Assamese fade into the background. As he put it, these events aren’t just talks—they’re the spark that keeps a language breathing.

The day’s sessions had set the tone for that optimism. An analytical discussion on Jnanpith awardee Birendra Kumar Bhattacharyya’s works pulled in a full house, with Sahitya Akademi winner Anuradha Sarma Pujari at the forefront. The editor of Sadin and Satsori, and author of 27 books, including 12 novels like her debut Hridoy Ek Bigyapan—which gave voice to women’s inner worlds in ways that reshaped Assamese fiction—she joined media columnist Rupam Barua, storyteller Pranjal Sharma Basishtha, and researcher Smritirekha Bhuyan to unpack Bhattacharyya’s unflinching novels. They delved into Mrityunjay’s raw take on the Quit India Movement’s betrayals and Iyaruingam’s haunting look at the 1962 Sino-Indian War, set in Arunachal’s hills—titles that still force readers to confront insurgency, borders, and the quiet toll on everyday lives. Barua, known for his sharp essays on media and politics in collections like Xomoy aru Xongbadpatra and Mor Xongbad, Mor Xongram, added edges to the talk, questioning how these stories echo in today’s headlines. It wasn’t abstract theory; it was a group of voices piecing together why Bhattacharyya’s moral fire still burns.

Then came the workshop on nature literature, led by wildlife activist and writer Soumyadeep Dutta—a vivid admirer of Gautam Buddha’s teachings—who laid out how tales of rivers, rhinos, and floods aren’t just pretty words; they’re the roots that ground a society, teaching empathy for the land that’s always giving and taking back. Drawing from Assam’s own wild heart, he showed how such writing can heal divides, one story at a time.

The panel on Assamese translated literature rounded out the day with equal spark. Sahitya Akademi translation awardees Bipul Deuri and Diganta Biswa Sarma—himself a scholar of Indian knowledge systems, poet, and recent Professor of Practice at IIT Guwahati’s Centre for Indian Knowledge Systems—sat with young writer-translator Dr Nayanjyoti Sharma to map the growing world of cross-language flows. Sarma, who won his award for translating Sri Aurobindo’s works into Assamese, drove home a point that landed like a quiet thunderclap: honest translation isn’t a copy anymore—it’s original art, standing tall on its own. And Sanskrit? Far from a relic, it’s the deep well regional languages like Assamese draw from, essential for nourishing future words. Sharma chipped in with the real talk on hurdles and openings in moving stories between Assamese and beyond, leaving everyone nodding at the promise of more bridges.

Zoom out, and PLF fits into Assam’s buzzing litfest scene, a calendar as full as Bihu season. There’s the Brahmaputra Literary Festival in late November, hugging the river with ecology talks and folklore slams; Dibrugarh University Litfest in early February, pulling in over 120 writers from 25 countries for global chats; Guwahati International Literary Festival in autumn, blending Northeast voices with national heavyweights; and Rangoli Utsav in April, tying literature to Bohag Bihu’s spring vibes with folk readings and manuscript exhibits. With Assamese newly recognised as a classical language in October 2024, these spots—often free and open to all—aren’t just events; they’re lifelines, amplifying tribal tales, women’s stories, and eco-concerns while countering the pull of the mainstream. Hundreds to thousands show up each time, from tea garden workers to city scholars, proving literature here is as communal as a village haat.

As the final lamp flickered out and the crowd thinned into the November chill, no one bolted for the gates. A group of Tezpur students cornered Pujari for book tips, whispering how her stories made them braver on the page. An elder from Nagaon slipped a faded volume of Deori’s into a young reporter’s bag, murmuring, “This is the real Assam—read it before you chase the next ‘unrest’ angle.” Tea cups cooled on ledges as hugs stretched long, and somewhere in the mix, a quiet pact formed: next November can’t arrive soon enough. The third PLF hadn’t just ended; it had woven itself into the roots it celebrated, ensuring the stories—and the adda—keep going.

*Senior journalist