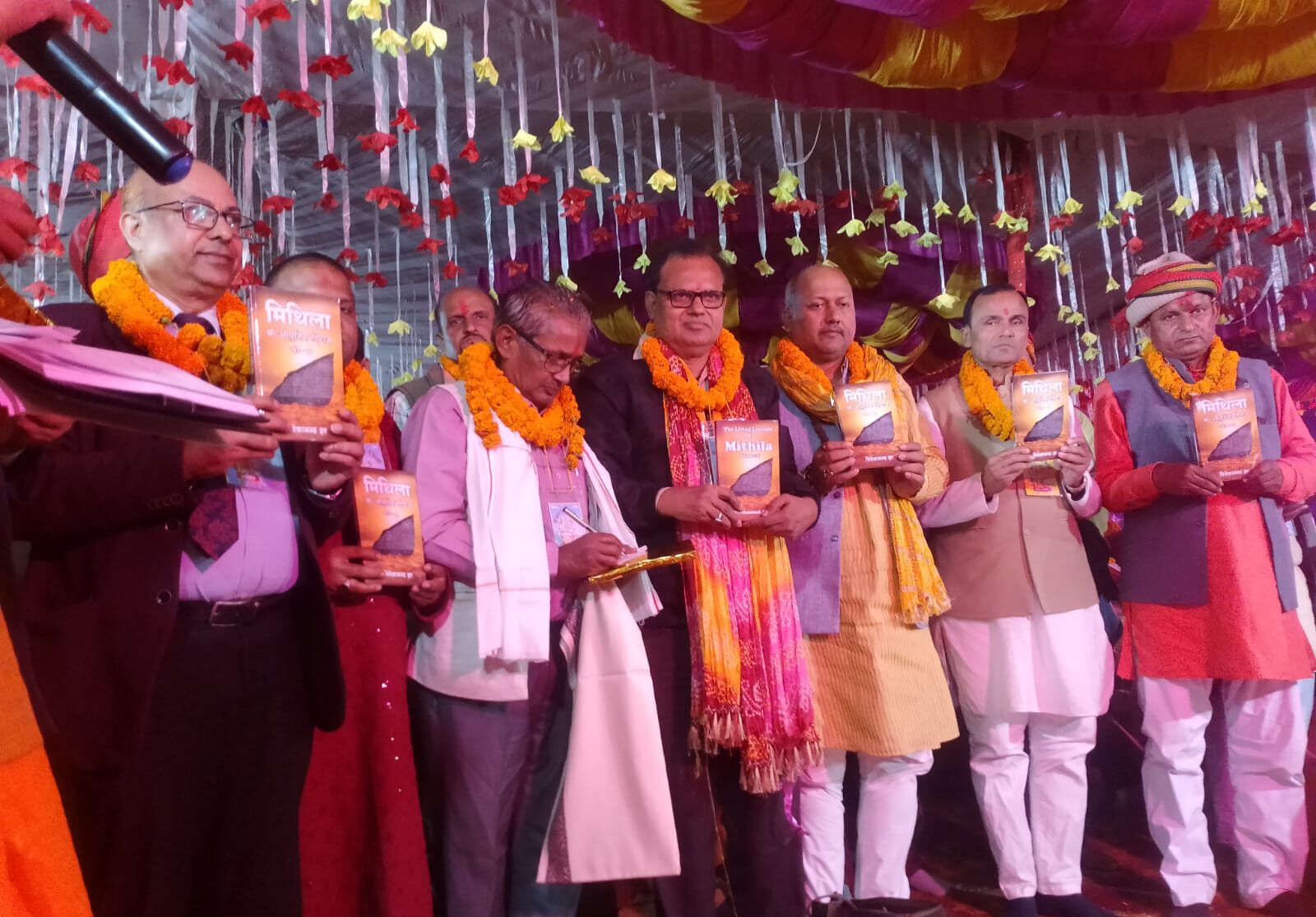

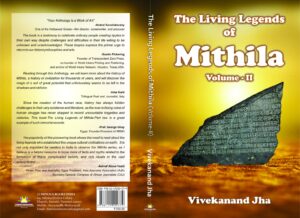

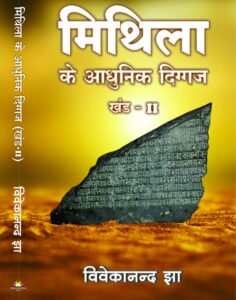

The Living Legends of Mithila Volume-II is the second book of a trilogy by author and columnist of Global Bihari, Vivekanand Jha. The anthology features 25 prominent personalities of the Mithila region of Bihar from different fields of life. Jha says that the criterion for being included in this book was that the achievers to be portrayed, ought to have contributed to the cause of Mithila.

The Living Legends of Mithila Volume-II is the second book of a trilogy by author and columnist of Global Bihari, Vivekanand Jha. The anthology features 25 prominent personalities of the Mithila region of Bihar from different fields of life. Jha says that the criterion for being included in this book was that the achievers to be portrayed, ought to have contributed to the cause of Mithila.

In the second series of ‘The Living Legends of Mithila’, the author continues to celebrate the remarkable achievements of Mithila’s most influential figures who are ordinary people with extraordinary achievements.

Mithila, a geographical landscape interspersed between two different sovereigns: India and Nepal, has its own civilisational history since tens of thousands of years ago. It is one of the world’s oldest and most culturally rich regions and has for centuries been a cradle of wisdom, spirituality, and learning.

Being a primordial civilisation, Mithila stands corroborated by the Bhagavad Gita, where Lord Krishna loftily speaks about King Janak, who ruled the landscape of Mithila, with his capital being Janakpur, the citadel of learning and erudition. From the revered King Janaka to the goddess Sita, Mithila’s influence on the cultural fabric of the Indian subcontinent is profound and enduring.

However, despite its glorious past, modern-day Mithila faces a reality marked by poverty, isolation and the devastating floods caused by the Kosi River, known as the “Sorrow of Bihar.”

The Legends of Mithila – Volume II brings together the stories of individuals who overcame great obstacles and through their hard work and dedication made significant contributions to their communities and beyond. Their lives are a testament to wisdom, resilience, and commitment to the common good—values that reflect the very essence of Mithila’s historical and cultural identity. Jha visited Jankapur, Kathmandu, Lehariaganj in Madhubani, Saurath, Malangia, Darbhanga, Sirhulli, Patna, Delhi, and Ranchi to portray the legends for the current series.

The book is in both English and Hindi, the latter is translated by Inderjeet Singh Parmar, who also designed the cover pages of the book.

“The trilogy will inspire the chivalric culture of the Mithila region for generations to come,” writes Parmanand Jha, the first Vice President of the Republic of Nepal, in the Foreword of the book.

Excerpts from a chapter on Dulari Devi from the book…

Ranti is a village in Madhubani district of Mithila. Much like all other villages, Ranti too possessed the similar features of naked impoverishment staring at its face, decades ago. Usually, the thatched houses dotted the village, with the community of labourers struggling day in and day out to make both ends meet. However, Ranti, unlike most of the villages in Mithila, over the passage of decades, has come to showcase the unique and spectacular achievement which became an object of envy for others: The village has come to flaunt the trinity of Padma Shri, namely, Maha Sundari Devi, Godawari Dutta and Dulari Devi. Today when Dulari Devi’s story is to be unfolded to the whole world, the other two Padma Shri, as aforesaid, are no more. Whereas the name of Godawari Devi is written in golden letters in the history of Mithila Paintings, Maha Sundari Devi too stands immortalised in the annals of the world of Mithila Paintings.

Dulari Devi, born in a fisherman’s family to Musar Mukhia and Dhaneshari Devi, had three sisters and one brother. Unfortunately for the whole family, Musar Mukhia died, leaving the family in deep distress. With the male member of the family having left for his heavenly abode, the huge burden of responsibility invariably fell upon Dhaneshari Devi for feeding her four children, which was a Himalayan task. Dulari Devi was the third daughter in sequence, who stayed back home with her brother, while their mother, along with their three sisters, would go to toil in the field. They would sow seeds as well as extend their labour during harvest; even on occasions, they would work in kilns and at sundry many places to make both ends meet. The grinding poverty in Mithila had afflicted its inhabitants in its octopus-like grip…

As Dulari Devi grew up to six years old, she too began toiling along with her mother. Significantly, while returning from her work, she would invariably stop at the residence of Karpuri Devi, whom she addressed as ‘Chachi Dai’. She would find Karpuri Devi often engaged in drawing paintings, which she would take a fancy to. Finding her beholden to her paintings, Karpuri Devi would chuckle, ‘Painting kenai sikhma ki, hamre lag rahi jo‘ (‘Will you learn painting? Stay with me’). Once, returning from Karpuri Devi’s house, Dulari Devi impulsively took a wooden stick and dug the ground to create a small hole, and she drew a fish. In the meanwhile, her drawing caught the attention of her mother, who angrily burst forth, ‘Bhikmanga chan, aar Bhikmanga bana chahaichan‘ (‘You are already a beggar, and you are further reconciled to being the same’). Dulari Devi replied, ‘Nae gae, Chachi dae ka dekhai chiyay ta mann bhel hamhu banabi‘ (‘No, beholding Chachi dae doing it, I too aspired to duplicate in my own way’). Mithila painting in those days had not much recognition, far less any assured earning; in fact, the artists of Mithila painting were toiling day in and day out to make both ends meet; it was never a rewarding profession. Small wonder then, beholding her daughter getting hooked on to the bandwagon of Mithila painting, far from exhilarating Dhanesari Devi, it inevitably put her off.

As mentioned above, the crippling poverty had grievously struck the family of Dulari Devi. In fact, the rice water (Maar) with some grains of rice mingled poured into a bucket, would arrive from the house of Maha Sundari Devi, which were distributed among Dulari Devi and three other sisters for their lunch.

The degree of impoverishment across Mithila in those years was the mirror reflection of scores of stories of Munshi Premchand. Moreover, as was the trend in Mithila in those days, the girls were married off much before the period of puberty; Dulari Devi was married while she was barely nine years old. Ironically, as fate would have it, all the fantasies of marital bliss which women longingly aspire for were never meant for Dulari Devi; in fact, the tragic childhood culminating in her marriage at the age of nine, when she hardly had the maturity to grasp its meaning, remarkably took a turn for the worse: barely had she experienced the bliss of motherhood, giving the birth to a girl child, the latter perished after six months of her birth. The Himalayan sorrow befell Dulari Devi: barely after she lost her daughter, she lost her place at her in-laws’ home. She returned to Karpuri Devi’s house, where she stayed for twenty-five years, learning the tricks of Mithila painting. In fact, Karpuri Devi was the source of her inspiration for learning the nuances of Mithila Painting…

In 2012- 13, Dulari Devi went on to win the state award for Mithila Painting…The year 2021 was a watershed year in her life: The year she was awarded Padma Shri, the fourth-highest Civilian Award. It was a dream come true for a woman who had struggled all throughout her life. She is the third recipient of Padma Shri after Maha Sundari Devi and Godawari Dutta in her village Ranti…

Dulari Devi’s love for Mithila is explicit in the following stanzas she melodiously sings.

“Saag pati tori tori ham gujara karebai, ham Mithila ma rahbai! Apan Kishori Ji ke ham charan dabebai, ham Mithila ma rahbai! Ahitham chai charudham, ham Mithila ma rahabai!’ (Plucking the saag leaves, I will lead my humble life, yet I will live only in Mithila! I will be massaging the sacred feet of our Kishori Ji [Sita], I shall live only in Mithila! All the four consecrated Dhams are located here, I will only stay in Mithila!’.)

– global bihari bureau