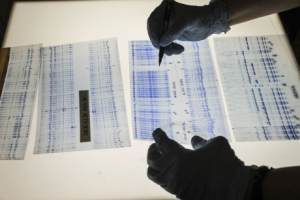

Innovative technologies such as Whole Genome Sequencing help identify and track water-borne pathogens at their source. ©FAO/Ferenc Isza.

Even as water is one of the world’s most precious resources, global water quality is deteriorating at an alarming rate, and land and water resources around the world are at a breaking point, according to FAO’s latest report on the State of the World’s Land and Water Resources for Food and Agriculture.

Globally, about 80 per cent of wastewater is discharged into the environment without adequate treatment, and one-third of all rivers, deltas and tributaries in Latin America, Africa and Asia are severely polluted with pathogens, putting the health of millions of people at risk.

Water quality also impacts food quality, and it is an important aspect to manage throughout the entire supply chain, from production to consumption. Foodborne illnesses are often a result of consuming food contaminated by poor-quality water.

Water connects us all and is essential to everything we do. Water is also vital for agriculture, livestock and fisheries and key to food production, nutritional security and health. Even though access to clean water and safe, nutritious food is a basic human right, every year around the world, over 420 000 people die and some 600 million people – almost one in ten – fall ill after eating contaminated food. Contaminated food hampers socioeconomic development, overloads healthcare systems and compromises economic growth and trade.

Prevention is better than a cure, and water quality and food safety risks are best addressed simultaneously at the farm level. Managing water quality in the context of food safety will reduce the exposure to harmful pathogens in water and the resultant food supply.

Through its One Water One Health programme, FAO is expanding the use of technologies, such as Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), to study the genomes of pathogens and track their path from water to food in order to prevent food contamination at its source. By incorporating water quality into food safety considerations and applying genomic surveillance to this process, the programme is enabling countries to address water and food quality as an integrated issue.

Currently, FAO is running a pilot in six countries where using WGS for surveillance of pathogens from water to food has never been done. As one example, FAO is working with Indonesia’s National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) to implement a genomic study on water quality in chicken-fish farming systems in Blitar, East Java. A common practice in this area, integrated chicken-fish farming involves raising chickens alongside fish. Connecting these systems allows the manure from chickens to fertilize pond water and generate food for fish. Manure is a very efficient fertilizer, generating phytoplankton and zooplankton growth that fish then eat.

For farmers, there is a clear advantage for these systems as there is no supplementary expenditure on fish feed. However, the risk of contaminants and disease to fish stock and the environment is relatively high, and poor sanitation and biosecurity can be an issue if the system is not properly managed. By using WGS, the BRIN study is tracking potential pathogens that move from water to fish, as well as investigating any potential antimicrobial resistance (AMR) of pathogens in the water.

Innovative WGS technology provides rapid identification and characterization of microorganisms with a level of precision not previously possible. With the vast application of this technology and lowering costs, WGS could, in the years to come, fundamentally change land and water management approaches for preventing food contamination at its source, contributing to greater consumer protection, trade facilitation and food and nutrition security.

“Prevention is the best strategy. For this, we must ensure that knowledge of pre-harvest factors in food safety, particularly regarding water quality, is built into food production globally,” FAO stated today. This is particularly crucial as global water scarcity pushes us towards the use of poor-quality water sources. A better understanding of the connections between water quality and food safety is needed to safeguard human health, implement sustainable agriculture and improve environmental outcomes.

Ultimately, WGS and novel approaches to water quality and food safety monitoring and surveillance will contribute to this global understanding and help prevent foodborne illnesses before they start, FAO hoped.

Source: the FAO News and Media office, Rome

– global bihari bureau