Barapani Lake, Meghalaya

First Block-Level Climate Check Alarms Meghalaya

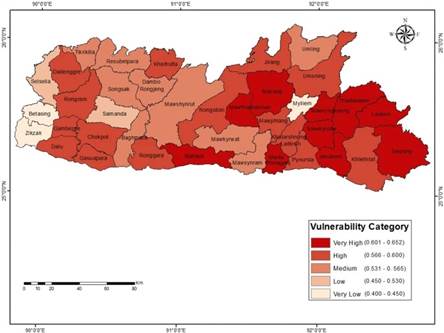

Shillong: The Meghalaya Climate Change Centre has delivered the state’s sharpest climate warning yet: of its 39 Community and Rural Development blocks, 25 are now classified as high or very high vulnerability. Published in Discover Sustainability under the National Mission for Sustaining the Himalayan Ecosystem, this is the first assessment to map risk at the scale where people actually live, farm, and vote—moving beyond district averages.

At the top of the list sits Thadlaskein in West Jaintia Hills, with a Vulnerability Index of 0.651, followed by Ranikor (0.642) and Laskein (0.635). At the lower end—below 0.32—lie Zikzak, Betasing, and Mylliem. These numbers, derived directly from the study, translate into lived reality.

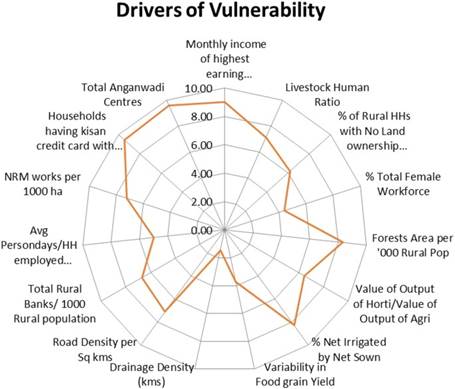

In Thadlaskein and its neighbours, steep 25–35° slopes, scarred by decades of rat-hole coal mining, shed soil during sudden monsoon bursts. Irrigation reaches fewer than one in ten farmers, and when the rains fail, betel-leaf vines wither, Lakadong turmeric yields collapse, and the lone road to Jowai disappears under landslides for days. One Anganwadi centre serves 1,800–2,000 children, contributing to a stunting rate near 27 per cent (NFHS-5). External state data further contextualises the picture: 32 of Meghalaya’s 39 blocks report average monthly household earnings below ₹5,000 (Meghalaya Economic Survey 2023–24), and 29 blocks have irrigation coverage under 20 per cent.

Across the state, more than 4,000 natural springs—critical drinking and irrigation sources for 70–90 per cent of rural households—have dried or become seasonal in recent decades. In the Khasi and Jaintia hills, women now walk twice as far in March and April to collect water compared with a generation ago. Forest loss, shorter jhum cycles, and poorly drained roads have disrupted the recharge zones that once fed perennial springs.

Moving west, medium-risk blocks such as Mawphlang, Umsning, and Rongara (around 0.50 on the Vulnerability Index) retain thicker sacred groves, more reliable broom-grass and pineapple yields, and slightly better irrigation networks—roughly double that of Thadlaskein. Targeted investment of ₹10–15 crore per block in springshed rejuvenation and micro-lift irrigation could push them into the safer zone within a five-year plan cycle.

In the flatter Garo plains, the landscape and vulnerability shift decisively. Rubber and areca-nut plantations replace shifting cultivation; irrigation reaches one field in four; Kisan Credit Cards are routine; and community forest committees pay dividends. Household incomes are frequently double those in the eastern hills, child stunting runs seven points lower, and farmers can ride out a failed monsoon. The gap between Thadlaskein and Zikzak is not just numbers—it is the difference between losing an entire month’s harvest every alternate year and selling latex to tyre factories.

Overlaying ethnicity and history sharpens the pattern. The most vulnerable blocks are concentrated in the matrilineal Khasi and Jaintia hills, where colonial revenue systems preserved clan land ownership, coal barons extracted resources and disappeared, and sacred groves—though magnificent—cover too little area to buffer modern pressures. The safest blocks cluster in the Garo plains and around Shillong, where missionary education, post-independence plantation drives, and different land traditions created an earlier path out of subsistence farming.

The state-wide context underscores urgency: irrigation covers just 14.45 per cent of cultivable land; monsoons now end 10–15 days earlier than two decades ago (IMD trends); and the annual climate-adaptation allocation rarely exceeds ₹80 crore (state budget 2024–25). Scaling interventions to lift the ten most distressed blocks to medium risk would require ₹1,200–1,500 crore over five years—an order of magnitude beyond current resources.

The findings underscore the importance of integrated climate adaptation planning at the grassroots level and contribute to the broader national agenda of building a climate-resilient Himalayan ecosystem.

The report’s prescriptions are pragmatic and grounded in proven practice elsewhere in the Northeast: ring-fenced climate-resilience funds, dedicated block-level Climate Resilience Officers who can converge schemes, zero-interest climate credit lines, large-scale springshed revival using geophysical mapping and contour trenching, village-managed early-warning systems in local languages, and politically harder measures such as temporary moratoriums on mining and payments for ecosystem services to protect steep forests. In Mizoram and Nagaland, similar efforts have restored two-thirds of treated springs through the dry season, boosting flow 30–50 per cent for minimal cost and measurable local impact.

For Meghalaya, the stakes are concrete. Eight out of ten people still depend directly on rain-fed fields, forests, and springs. Children’s growth, household livelihoods, and entire ecosystems hang in the balance. The Himalayan foothills are warming half a degree faster than the national average, and 64 per cent of the state now lies on the wrong side of the resilience line. The study’s maps name villages, hills, and water sources at risk—the diagnosis is complete, the prescription written, and the trenches marked. Now, the political will and resources must follow.

– global bihari bureau