A Melody That Became a Movement

Six Syllables, Timeless Thunder

Vande Mataram was initially composed independently.

It was included in Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s novel Anandamath (published in 1882).

It was first sung by Rabindranath Tagore at the 1896 Congress Session in Calcutta.

Vande Mataram, as a political slogan, was first used on 7 August 1905.

The song was adopted as India’s National Song by the Constituent Assembly in 1950.

Today, November 7, 2025, midnight drapes India in velvet silence, and a 150-year-old anthem stirs the air like incense rising from a thousand temple lamps. Vande Mataram—six syllables forged in the crucible of devotion—throbs through the veins of a nation, its cadence older than the tricolour that now flutters in the breeze, carrying whispers of rivers, fields, and unyielding resolve.

The tale unfolded in 1875, within the intimate glow of a Calcutta chamber where an oil lamp cast steady amber shadows, its flame dancing gently to the monsoon’s rhythmic patter on tin roofs. Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, a luminary of Bengali literature and architect of modern prose, hunched over sheets of foolscap, the sharp tang of fresh ink blending seamlessly with the earthy perfume of camphor and rain-drenched soil. Born in 1838 in the quiet village of Naihati, Bankim had already woven magic into the literary world with novels like Durgeshnandini in 1865, a romantic saga of Rajput valour that stirred hearts with its vivid depictions of courage and love, and Kapalkundala in 1866, where mystical forests and human passions intertwined under moonlit skies. His works, rich with social commentary and cultural depth, reflected a colonised society yearning for identity. Now, in this lamp-lit sanctuary, his quill flowed with effortless grace, blending the majestic cadence of Sanskrit with the tender intimacy of Bengali. He envisioned a divine mother—Bharat Mata—adorned in rivers that cascaded like liquid silk over sun-kissed skin, fields of golden wheat undulating in breezes that carried the sweet sigh of harvest, the crescent moon resting as a luminous tilak on her serene brow. Yet, beneath this splendour, cold iron chains clinked against her ankles, biting into flesh that symbolised a homeland in bondage. With profound reverence, he infused her with voice: Vande Mataram. The hymn, a masterpiece of poetic synthesis, emerged not as mere verse but as a spiritual invocation, slipping quietly into the pages of Bangadarshan, the literary journal he founded and edited. There, amid articles on philosophy and folklore, it lay like a seed in fertile black soil, absorbing the warmth of unspoken aspirations, waiting for the right season to sprout.

As seven monsoons cycled through, drenching the land in renewal and reflection, that seed burst forth in Bankim’s monumental novel Anandamath, serialised first in Bangadarshan’s issues from March-April 1881 before its full publication in 1882. The narrative transported readers to a hidden forest monastery, where the air hung thick with the heady sweetness of ripe mangoes dangling from ancient branches, marigold garlands wilting softly in the humid embrace, and fireflies pulsing like living embers in the twilight. Here, a band of ascetic warriors—the Santanas, meaning “children” of the motherland—gathered in solemn devotion. Clad in saffron robes that rustled like autumn leaves, their bare feet pressed into cool, moss-covered earth, they encircled a sacred temple housing three evocative idols. The first embodied the mother as she had been: resplendent in ancient glory, her form gilded in torchlight that spilt honeyed warmth across the stone, evoking eras of empires and epics. The second knelt in the present wretchedness, dust clinging to her like the grime of subjugation, her eyes downcast in silent sorrow. The third stood poised for the future, dawn’s first blush already kindling in her gaze, promising rebirth and radiance. In this hallowed space, the Santanas chanted Vande Mataram, their voices rising in harmonious waves—deep baritones blending with tenor fervour—carried on breezes laced with the salty tang of distant oceans, rustling palm fronds into a symphony of approval. The song became the heartbeat of their “religion of patriotism,” a creed where love for the land transcended ritual, demanding sacrifice and steel-willed resolve. As Sri Aurobindo later articulated, this was no mendicant’s plea but a vision of the mother wielding trenchant steel in her seventy million hands, a call to awaken from colonial delusions.

The anthem’s public ascension began in 1896, at the Indian National Congress session in Calcutta’s bustling pandal, where the air hummed with the rustle of silk dhotis and lungis, the wilting fragrance of jasmine garlands heavy in the sweltering heat, and the faint aroma of tea steaming from clay cups. Rabindranath Tagore, the bard of Bengal with his flowing beard and soulful eyes, stepped forward to render the melody for the first time in public. His voice, rich and resonant like the Ganges in full flow, lifted the hymn skyward, wrapping the assembled delegates—merchants from Bombay, scholars from Madras, reformers from Punjab—in tendrils of sacred smoke. Hearts synchronised, pulses quickened; the song, once confined to pages, now breathed life into a collective dream.

The dream ignited into flame in 1905, as Lord Curzon’s partition of Bengal cleaved the province like a cruel axe, sparking outrage that simmered into the Swadeshi movement. On August 7, Vande Mataram transformed from hymn to slogan, shouted in streets glistening with morning dew. In North Calcutta, the Bande Mataram Sampradaya was formed, a devoted society treating the motherland as a divine mission. Every Sunday, members embarked on prabhat pheris—dawn marches—bare feet padding softly on cool, mist-kissed cobblestones, clay diyas flickering golden light on determined faces, the air alive with the metallic clink of voluntary contributions dropped into tins for the cause. Tagore himself occasionally joined, his presence a benediction, his voice mingling with the youthful chorus sharp as forged steel. The movement swelled southward to Barisal in May 1906, where over ten thousand marchers—Hindus and Muslims united in a human river—paraded through main thoroughfares, hand-stitched flags bearing Vande Mataram snapping crisply in the wind, their colours vivid against the backdrop of palm-lined streets. The chant rolled like thunder, tasting of shared salt and unyielding spirit.

British authorities, alarmed by this surging tide, responded with iron-fisted repression. Circulars prohibited the song in schools and colleges of the new Eastern Bengal province, threatening derecognition and expulsion. In November 1905, in Rangpur, 200 schoolboys faced fines of five rupees each for chanting defiantly; they pooled warm copper coins from pockets, the metal heavy with the day’s defiance, and sang even louder, their voices echoing off colonial bungalows. Leaders were coerced into roles as special constables to stifle the cries, yet the melody persisted. In April 1906, at the Bengal Provincial Conference in Barisal, bans escalated to outlawing the gathering itself; delegates raised the slogan anyway, facing lathi charges that cracked like thunder on flesh, blood warm and metallic, mingling with dust. Lahore in May 1907 saw young protesters marching against arrests, their chants met with brutal force, yet the air filled with the scent of resilience. In Dhulia, Maharashtra, in November 1906, a public meeting erupted in Vande Mataram cries. Belgaum, Karnataka, 1908: as Lokmanya Bal Gangadhar Tilak was deported to Mandalay, boys endured thrashings and arrests for violating verbal prohibitions, the ground stained but the song unsilenced.

The anthem’s reach extended to the toiling masses. On February 27, 1908, in Tuticorin, Tamil Nadu, a thousand workers from the Coral Mills struck in solidarity with the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company, marching late into the night under a canopy of stars, cotton lint drifting like ethereal snow in their hair, the refrain weaving through the sharp scent of loom oil, sea brine, and midnight jasmine. In Bombay, June 1908, thousands swarmed outside the police court during Tilak’s trial, bodies pressed in a sea of sandalwood incense and perspiration, voices shaking the very foundations of justice. Tilak’s release in Pune on June 21, 1914, drew ecstatic crowds; the chant persisted long after he seated himself, throats raw but spirits soaring into the velvet dusk.

Beyond India’s shores, the song became a beacon for revolutionaries. In Stuttgart, Germany, 1907, Madam Bhikaji Cama, a fiery Parsi patriot, raised the first tricolour flag outside India at the International Socialist Congress, its saffron, white, and green panels emblazoned with Vande Mataram in bold scarlet threads that caught the European sun like fresh vermilion, the silk whispering promises of liberty against her steadfast hands. In Paris, 1909, Indian exiles launched a magazine titled Bande Mataram from Geneva, its pages crisp with the glue of secrecy and the urgency of smuggled ink. On August 17, 1909, in London’s Pentonville Prison, Madan Lal Dhingra, assassin of Curzon Wyllie, ascended the gallows; the rough hemp noose grazed his throat, but his final words—“Bande Mataram”—emerged warm and unwavering, causing even the executioner to pause. In Cape Town, October 1912, Gopal Krishna Gokhale arrived to a grand procession, the harbour air thick with salt spray and the rolling wave of voices greeting him with the anthem’s embrace.

Intellectual firebrands amplified the call. In August 1906, an English daily named Bande Mataram launched in Calcutta under Bipin Chandra Pal’s editorship, with Sri Aurobindo soon joining as co-editor. Its editorials, sharp as khadga blades, preached self-reliance and unity, the newsprint smelling of fresh presses and revolutionary ink, awakening readers from Bombay to Madras.

The crescendo built through decades of struggle, the song a constant companion in rallies, jails, and secret meetings—from Punjab’s fertile plains where wheat fields bowed in sympathy, to Bombay’s crowded chawls echoing with midnight rehearsals. It infused the freedom movement with cultural pride and spiritual fervour, uniting castes, creeds, and tongues in a moral symphony against oppression.

Independence dawned, and on January 24, 1950, the Constituent Assembly in New Delhi, its halls scented with fresh plaster and the faint polish of wooden benches, sealed the anthem’s legacy. Dr Rajendra Prasad addressed the House with quiet authority: no formal resolution needed, for unanimity reigned. Jana Gana Mana, composed by Tagore, became the National Anthem; Vande Mataram, having played a historic role in the crucible of freedom, received equal honour as the National Song. Applause erupted like monsoon torrents, a tidal wave carrying the mother from myth to mantle.

Exactly 150 years from Bankim’s lamp-lit creation, the nation has erupted in commemoration to honour its enduring legacy as a song of unity, resistance, and national pride. Institutions, cultural bodies, and educational centres are organising seminars, exhibitions, musical renditions, and public readings to revisit the song’s historical and cultural significance.

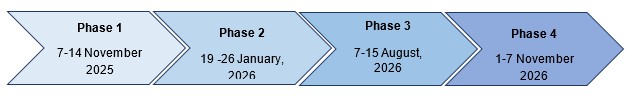

The Government of India will commemorate this in four phases.

In Delhi’s Indira Gandhi Stadium, transformed into a colossal amphitheatre under floodlights bright as harvest moons, the inaugural ceremony will unfold with grandeur today. Prime Minister Narendra Modi will inaugurate the year-long commemoration of the National Song “Vande Mataram” at around 9:30 AM at the Stadium.

Singers from every corner—Ladakh’s high-altitude tenors where breath frosted in crystalline air, Kerala’s coastal sopranos redolent of coconut groves and backwater spice, Manipur’s ethereal choruses from lotus-veiled phumdis, Rajasthan’s desert baritones echoing dunes of sand—will converge in adaptations that spanned raag and rap, folk and fusion. The atmosphere pulses with the sizzle of street chaat, the sweetness of jalebi syrup, and the collective hum of anticipation.

According to the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, a commemorative stamp will be unveiled by the Prime Minister, Bankim’s thoughtful profile etched beside Bharat Mata’s serene visage, the paper crisp and fragrant under flashing cameras. Modi will also release a silver coin. An exhibition hall adjacent will buzz with artefacts: original Bangadarshan pages yellowed with age, faded flags from Barisal processions, lathis once wielded in repression now silent witnesses. Short films will be screened in loops—quill dipping into inkwells with a soft plop, forest monasteries alive with chant, Rangpur boys counting fines in clinking coppers, Stuttgart’s flag unfurling in slow motion, dawn breaking rose-gold over the Yamuna—each frame a sensory portal to the past.

The festivities will cascade nationwide from today, from metropolitan hubs to remote tehsils. VIP events blended with public fervour: village squares lit by Petromax lamps, school grounds alive with children’s recitations, town halls hosting debates scented with tea and samosas. Photos and videos will flood a dedicated campaign website, capturing smiles glistening with pride, flags waving in synchronised rhythm.

The year-long symphony will unfold in phases. All India Radio and Doordarshan will broadcast special programmes—morning ragas melting into evening ghazals, all laced with Vande Mataram variations, the airwaves humming like sitar strings in mango-scented summers. FM stations pulsed with youth remixes. In Tier 2 and 3 cities, panel discussions will unfold under ceiling fans whirring lazily, as scholars and locals sip chai while dissecting the song’s layers. Indian missions abroad will host cultural evenings: embassies in Washington fragrant with curry leaves, Paris salons echoing tabla beats, Tokyo gardens blooming with cherry blossoms and Bengali verses. A global music festival will dedicate stages to the anthem, artists from diaspora communities blending dhol drums with didgeridoos.

Environmental homage will bloom in “Vande Mataram: Salute to Mother Earth”—tree plantation drives where saplings will sink into loamy soil still warm from sun-baked days, hands caked in mud, leaves unfurling like green stanzas under nurturing rains. Patriotic murals will adorn highways: vast canvases of saffron warriors charging through emerald fields, indigo rivers flowing toward sapphire horizons, the fresh tang of paint mingling with the diesel fumes and the scents of wildflowers. Railway stations and airports will feature LED displays scrolling histories, announcements booming over platform chatter, while audio messages will play in trains, blending with the rhythmic clatter of wheels on tracks.

Digital outreach will surge with twenty-five one-minute films, each a gem: Bankim’s early life in Naihati’s dusty lanes, the Santanas’ forest vigils, Rangpur’s defiant schoolyard, Barisal’s unified march, Cama’s flag-raising winds, Dhingra’s gallows whisper, Tilak’s courtroom solidarity, and modern interpretations linking past to present. These clips will be virally spread across social media, screens glowing in late-night scrolls.

The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting says the Vande Mataram Campaign will fuse seamlessly with Har Ghar Tiranga, every household hoisting the tricolour from balconies aglow with diyas, the night air rich with ghee flames, marigold strings, and the collective inhale of a nation reborn.

In this sesquicentennial embrace, Vande Mataram transcends time. From Bankim’s solitary quill to stadium crescendos, from whispered rebellions to global festivals, it remains the soul’s unquenchable fire—unity in diversity, sacrifice in devotion, pride in heritage. Tonight, a child on a rooftop, fingers sticky with mishri, tugged an elder’s kurta, inhaling the mingled scents of rain-soaked earth in a remote corner of the country, flickering oil, and distant incense. “Why do we sing?” she asked, eyes wide as the full moon. The elder knelt, voice soft as Ganges dawn: “Because 150 years ago, a poet gave our mother a voice, and she taught us to roar.” The flame danced higher, the flag fluttered prouder, the child’s heart swelled—already echoing the eternal verse, scented with soil, steel, and boundless tomorrow.

– global bihari bureau